Latest News

No surprises in uncontested Sunderland races

No surprises in uncontested Sunderland races

Buckland backs short-term rental bylaw

Buckland backs short-term rental bylaw

Providing opportunity for people to grow: The United Arc of Franklin County’s annual Gardening with Steve event a highlight of spring

Steve McConley credits his wife, Doreen, for his interest in growing plants. Doreen brought solid gardening skills to their union, and Steve appreciates her encouragement. The McConleys have a garden at their Bernardston home, and now Steve shares...

Change in federal drug classification could help cannabis shops

In the wake of the Justice Department’s proposal to reclassify cannabis as a less dangerous drug, dispensary owners say the change would help their business, especially on taxes.“The immediate impact would be for the government to treat us like other...

Most Read

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

$12.14M school budget draws discussion at Montague Town Meeting

$12.14M school budget draws discussion at Montague Town Meeting

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

Streetlight decision comes to Shelburne Town Meeting

Streetlight decision comes to Shelburne Town Meeting

Editors Picks

Greenfield Notebook: May 6, 2024

Greenfield Notebook: May 6, 2024

PHOTO: River runway

PHOTO: River runway

North County Notebook: May 7, 2024

North County Notebook: May 7, 2024

Regional Notebook: May 6, 2024

Regional Notebook: May 6, 2024

Sports

Bulletin Board: Scoville, Conte help Westfield State softball capture MASCAC regular season title

Stephanie Scoville helped pitch the Westfield State softball team to a MASCAC regular season title on Saturday, throwing a complete game, striking out nine and scattering six hits as the Owls beat Bridgewater State, 4-2. The win sealed Westfield’s...

Fit to Play with Jim Johnson: Why Pickleball?

Fit to Play with Jim Johnson: Why Pickleball?

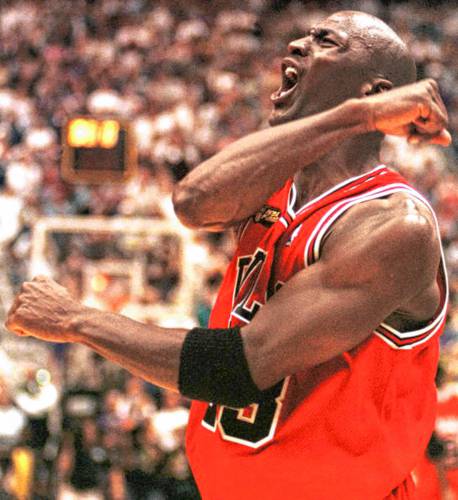

Softball: Franklin Tech pulls away from Hopkins, 8-3 (PHOTOS)

Softball: Franklin Tech pulls away from Hopkins, 8-3 (PHOTOS)

Opinion

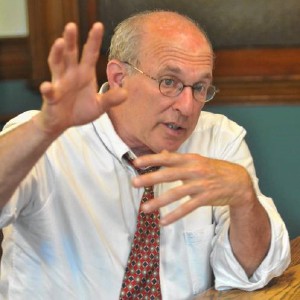

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Columnist’s note: The following contains many parenthetical asides and seemingly unimportant details that somehow, one hopes, lead to a conclusion that the reader finds moderately interesting or entertaining or, at the very least, bearable. Once...

Shirley and Mike Majewski: Vote for Blake Gilmore

Shirley and Mike Majewski: Vote for Blake Gilmore

Kathy Sylvester: Vote for expertise on May 6

Kathy Sylvester: Vote for expertise on May 6

Bernie Sadoski: Blake Gilmore is committed to his community

Bernie Sadoski: Blake Gilmore is committed to his community

Business

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

GREENFIELD — Three decades ago, Sean and Darren Pierce, two brothers in their mid-20s, decided to start selling coffee — a business venture that was funded by a roughly $30,000 mountain of credit card debt.Today, the Greenfield-based Fogbuster Coffee...

Goddard finds ‘best location’ in Shelburne Falls with new Watermark Gallery space

Goddard finds ‘best location’ in Shelburne Falls with new Watermark Gallery space

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

Arts & Life

Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song

We’ve reached that point in the school year when it is actually painful (I mean physically painful) for me to leave my yard in the morning. May is the true month of the reawakening and blooming of Nature’s splendor and last week she was in full...

Obituaries

Edwin J. Nartowicz

Edwin J. Nartowicz

Northampton, MA - Edwin J. Nartowicz, 100, of Northampton, passed away on Thursday, April 25, 2024, surrounded by his loving family at Cooley Dickinson Hospital. He was born in South Deerfield on November 7, 1923, to the late John and A... remainder of obit for Edwin J. Nartowicz

Karen R. Adams

Karen R. Adams

Karen R Adams Bernardston, MA - Please join us as we celebrate the life for Karen R Adams on Saturday May 25, 2024, at Mt Toby Friends Meetinghouse located at 184 Long Plain Rd Leverett MA. Service will begin at 11:00 am, please join us ... remainder of obit for Karen R. Adams

Susan R. Johnson

Susan R. Johnson

Greenfield, MA - Susan R. Johnson, 53, passed away unexpectedly on April 25, 2024. She was born in Gardner, MA on April 26, 1970 the daughter of Rene and Margaret (Ackert) Charette. She enjoyed going to the beach, tanning and art. S... remainder of obit for Susan R. Johnson

James F. Millar

James F. Millar

James "Jack" F. Millar Sunderland, MA - James "Jack" F. Millar, 74, of Amherst Road died unexpectedly Friday 4/26/24 at the Baystate Franklin Medical Center in Greenfield. He was born in Northampton on January 6, 1950, the son of James a... remainder of obit for James F. Millar

Serious barn fire averted due to quick response in Shelburne

Serious barn fire averted due to quick response in Shelburne

Employee pay, real estate top Erving Town Meeting warrant

Employee pay, real estate top Erving Town Meeting warrant

Western Mass school leaders rally for funding at State House

Western Mass school leaders rally for funding at State House

Franklin County reps speak to House budget amendments

Franklin County reps speak to House budget amendments

Colrain voters to decide Selectboard, moderator races

Colrain voters to decide Selectboard, moderator races

Longtime moderator retains position in Ashfield election

Longtime moderator retains position in Ashfield election

‘We are among the leaders’: Ashfield Town Meeting voters pass bevy of clean energy proposals

‘We are among the leaders’: Ashfield Town Meeting voters pass bevy of clean energy proposals

High Schools: Greenfield girls tennis wins second match in a row following 4-1 triumph over PV Christian (PHOTOS)

High Schools: Greenfield girls tennis wins second match in a row following 4-1 triumph over PV Christian (PHOTOS) Bulletin Board: Liam Kerivan and Spencer Towne pitch Pipione’s past TFAC

Bulletin Board: Liam Kerivan and Spencer Towne pitch Pipione’s past TFAC Michelle Caruso: Questions candidate’s judgment after 1980s police training incident

Michelle Caruso: Questions candidate’s judgment after 1980s police training incident The house that therapy built: Multimedia artist Lisa Winter to display “My House” at the Wendell Meetinghouse this Sunday

The house that therapy built: Multimedia artist Lisa Winter to display “My House” at the Wendell Meetinghouse this Sunday Fun Fest returns to Turners Falls: Música Franklin hosts 6th annual family-friendly, free event, May 11

Fun Fest returns to Turners Falls: Música Franklin hosts 6th annual family-friendly, free event, May 11 Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses

Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses Let’s Talk Relationships: Breaking up is hard to do: These tools can help it feel easier

Let’s Talk Relationships: Breaking up is hard to do: These tools can help it feel easier