In the kitchen with Fannie Farmer: A brief history of the ‘Mother of Level Measurements’

|

Published: 01-16-2024 11:42 AM

Modified: 01-16-2024 11:48 AM |

Like many American home cooks, I own more cookbooks than I can use.

Over the years, hand-me-downs from family members, birthday gifts, and impulse purchases have brought more than 100 volumes to my kitchen shelves.

When I decide to try preparing a dish I have heard about but never made, I rummage through those shelves to compare versions in various culinary tomes.

Nine times out of ten at the end of this ritual quest I end up holding the same book in my hands: “The Fannie Farmer Cookbook.”

Fannie Merritt Farmer was born in Boston in 1857, one of four daughters of a printer and his homemaker wife. The Farmers were not wealthy, but they placed a high value on education.

Redheaded Fannie, the brightest of the lot, was originally destined for college. Her education was derailed when, as a high-school student, she became ill with what scholars believe was probably polio. It took her years to learn to walk again.

She would not find her true calling until she reached 31, when her family and the woman for whom she had been working as a mother’s helper encouraged her to enroll in the Boston Cooking School.

The school, which specialized in training teachers and professional cooks, was part of a late-19th-century movement toward scientific cookery.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

My Turn: Quabbin region will never see any benefits from reservoir

My Turn: Quabbin region will never see any benefits from reservoir

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

New USDA offices in Greenfield to aid staffing increase, program expansion

New USDA offices in Greenfield to aid staffing increase, program expansion

Longtime Orange public servant Richard Sheridan dies at 78

Longtime Orange public servant Richard Sheridan dies at 78

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

Four Rivers boys knock off Xaverian to win Four Rivers Ultimate Tournament on Saturday (PHOTOS)

Four Rivers boys knock off Xaverian to win Four Rivers Ultimate Tournament on Saturday (PHOTOS)

Farmer succeeded so well in her studies that at her graduation she was asked to serve as assistant to the school’s director, Carrie M. Dearborn. When Dearborn died a few years later, Farmer was the obvious choice to take over the school.

She increased its enrollment by broadening its appeal, targeting young ladies training to be homemakers. In 1901 she split off from the Boston Cooking School to start her own successful academy, Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery.

Before that departure, however, in 1896, Farmer took charge of revising and expanding the school’s main textbook, “The Boston Cooking School Cookbook.” She approached the Boston publisher Little, Brown about putting out a trade edition, arguing that it would sell well to the public.

With shortsightedness they must have rued long afterward, Little, Brown’s representatives refused to take on the project. They did allow themselves to be persuaded by the self-confident Fannie Farmer to serve as printers and distributors for the book.

Farmer paid the costs of publication and retained copyright. She thus took home the lioness’s share of the profits when the book enjoyed the success she had anticipated.

The 3000 copies of the original printing sold out quickly, and the book saw yearly reprintings and frequent revisions until Farmer’s death in 1915, when it was taken on by other authors and editors.

Now known simply as “The Fannie Farmer Cookbook,” the book is in its 13th edition.

Three major factors accounted for Farmer’s popularity as a teacher and as a writer. First, she had faith in herself and in her profession. “Progress in civilization,” she wrote in the first chapter of her cookbook, “has been accompanied by progress in cookery.”

Second, she enjoyed her work and expected her students and readers to enjoy preparing and eating food as well.

Laura Shapiro, who devoted a chapter of her book “Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century” to Farmer, explained, “While other cooks always insisted that their own preferences in food were simple and austere, Fannie Farmer liked to eat and didn’t mind saying so.” Her enthusiasm for food communicated itself to those around her.

Finally, in an era in which cooking was still largely an inexact science, Farmer streamlined its practice. She was known as the “Mother of Level Measurements.”

Shapiro recounted the probably apocryphal tale of a Boston Cooking School student who was confronted with recipes calling for pinches of salt and pats of butter the size of an egg. The student supposedly asked Farmer how big those pinches and eggs were supposed to be.

Perhaps in response to this sort of query, Farmer applied herself to the task of defining and reinforcing exact measurements. “Correct measurements are absolutely necessary to insure [sic] the best results,” she asserted in a section of her book titled “How to Measure.”

“A cupful is measured level … A tablespoon is measured level. A teaspoon is measured level.”

Contemporary historians downplay Farmer’s actual cooking skills. The New England Historical Society quotes the author’s niece, Wilma Lord Perkins, as saying that the maid did much of the cooking in Farmer’s childhood home. She called her aunt “a great executive, food detective, and gourmet, rather than a great cook herself.”

Nevertheless, no one denies that Farmer influenced generations of American cooks, both as a teacher and as a writer.

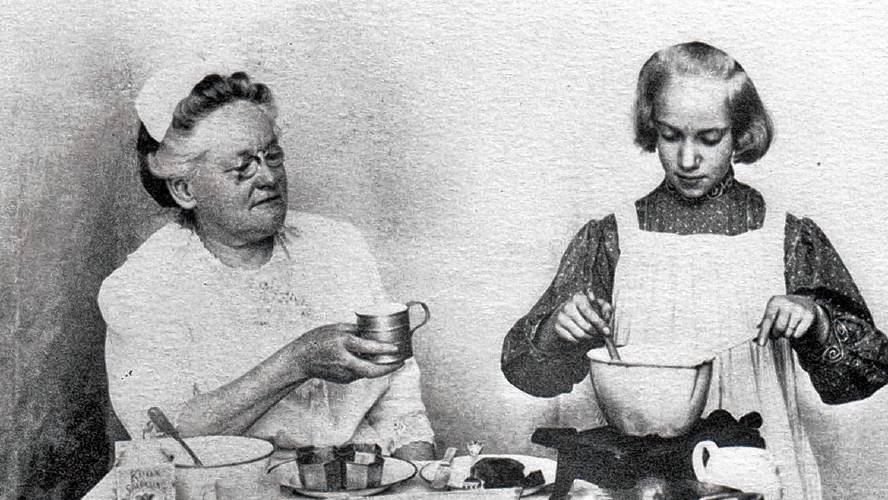

My maternal grandmother, Clara Engel Hallett, studied under Fannie Farmer.

The adopted child of well-to-do Vermont farmers, Clara was sent by her parents to take a course at Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery around 1910 to prepare for the culinary obligations of marriage to my grandfather.

My grandmother is now dead, and I never had the sense to ask her while she lived exactly what she learned at Fannie Farmer’s school.

From my many years of observing her in the kitchen — and from my perusal of Farmer’s first edition — I would guess that my grandmother learned to respect the basic food groups. Even when dining alone she never served dinner without a green salad, a vegetable, and some kind of starch.

I also surmise that her sweet tooth was reinforced by her months at the school. She clearly agreed with Farmer’s dictum that “pastry cannot easily be excluded from the menu of the New Englander.”

She took pride in her food’s appearance as well as its taste and always wore a frilly apron when she dished up a meal. And she passed on her love of basic cookery to my mother, who passed it on to me.

As well as valuing its inherent usefulness, then, I cherish my “Fannie Farmer Cookbook” for the ways in which it connects me to other people. Something about this substantial volume of substantial foods brings my grandmother back into the kitchen with me.

It also brings back my mother, who was a darn fine cook but who would have been lost without her 1965 edition of the cookbook.

It keeps me in conversation with my friend Pat Leuchtman of Greenfield, who favors the 1959 version. “I like it because it was my first cookbook — and because I never go away empty handed when I turn to it with a question,” she explains.

And it gives me the benefit of the wisdom of more than a century of experts on, and lovers of, cooking, from Fannie Farmer herself down to the most recent author, Marion Cunningham.

“Today, more than ever,” Cunningham wrote in the 1990 edition, “I sense a hankering for home cooking, for a personal connection to our food.”

To me, Fannie Farmer helps provide that connection.

This egg dish isn’t in the current edition of Fannie Farmer. It appeared in the one with which I grew up. I think it was called American Cheese Fondue.

I have made it without the Creole seasoning (which I added to the original recipe), but I like the little zing it adds to the recipe.

With or without that zing, the dish is what the late food writer and editor Judith Jones called “nursery fare”: tasty comfort food that is easy to eat and digest.

It uses ingredients that are almost always in the house, and it can be thrown together into a simple, satisfying supper very quickly.

Ingredients:

1 cup scalded milk

1/4 cup soft bread crumbs (I usually just crumble up bread)

1 cup shredded store cheese (Cheddar)

1 tablespoon sweet butter

1 teaspoon Creole seasoning or 1/2 teaspoon salt

3 egg yolks, beaten until they are thick

3 egg whites, beaten until they are stiff

Instructions:

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Butter a 1- or 1 1/2 quart casserole dish.

In a saucepan combine the milk, bread crumbs, cheese, butter, and seasoning. Cook, stirring, over low heat until the cheese and butter have melted and the mixture is smooth. Remove from the heat.

Stir in the egg yolks; then gently fold in the egg whites.

Pour the mixture into the prepared casserole dish. Bake for 20 to 30 minutes.

Serves 4 (as a light meal).

Tinky Weisblat is an award-winning cookbook author and singer known as the Diva of Deliciousness. Visit her website, TinkyCooks.com.

Speaking of Nature: Surprised by strawberries in the grass: Flowers will bloom whether you pay attention or not

Speaking of Nature: Surprised by strawberries in the grass: Flowers will bloom whether you pay attention or not From fair to fantastic: Memorial Hall Museum exhibit shows how Green River Festival blossomed over 37 years

From fair to fantastic: Memorial Hall Museum exhibit shows how Green River Festival blossomed over 37 years Valley Bounty: Fibers for farmers: Western Massachusetts Fibershed turns local ‘throw away’ wool into fertilizer pellets

Valley Bounty: Fibers for farmers: Western Massachusetts Fibershed turns local ‘throw away’ wool into fertilizer pellets Sounds Local: Joni Mitchell tribute comes to Turners Falls: Big Yellow Taxi to perform ‘Court and Spark’ in its entirety, May 18 at the Shea

Sounds Local: Joni Mitchell tribute comes to Turners Falls: Big Yellow Taxi to perform ‘Court and Spark’ in its entirety, May 18 at the Shea