Latest News

Bulky waste recycling event set for Saturday

Bulky waste recycling event set for Saturday

New fire engine gets nod at Warwick Town Meeting

New fire engine gets nod at Warwick Town Meeting

Erving voters say ‘no’ to $3.7M debt exclusion

Erving voters say ‘no’ to $3.7M debt exclusion

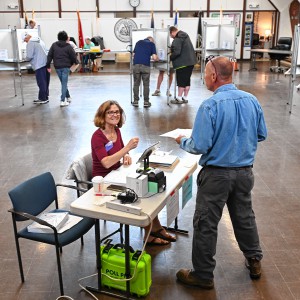

Slew of write-ins elected in Hawley

Slew of write-ins elected in Hawley

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

Editor’s note: This story will be updated.AMHERST — More than 130 people were arrested on the University of Massachusetts campus Tuesday night after those who set up a pro-Palestinian encampment on the South Lawn of the Student Union refused to...

New Salem election ushers in new Selectboard member

NEW SALEM — The town has a new Selectboard member following Monday’s annual town election. Mailande DeWitt, a University of Connecticut School of Law graduate who currently serves as a New Salem Public Library trustee, will fill a two-year vacancy on...

Most Read

Serious barn fire averted due to quick response in Shelburne

Serious barn fire averted due to quick response in Shelburne

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11

Political newcomer defeats Shores Ness for Deerfield Selectboard seat

Political newcomer defeats Shores Ness for Deerfield Selectboard seat

Roundup: Pioneer baseball wins Suburban League West title following 2-0 win over Hopkins

Roundup: Pioneer baseball wins Suburban League West title following 2-0 win over Hopkins

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

Employee pay, real estate top Erving Town Meeting warrant

Employee pay, real estate top Erving Town Meeting warrant

Editors Picks

On Mother’s Day, we’ll always have Paris: A crêpe recipe in honor of my French-speaking mother

On Mother’s Day, we’ll always have Paris: A crêpe recipe in honor of my French-speaking mother

Montague Notebook: May 8, 2024

Montague Notebook: May 8, 2024

Greenfield Notebook: May 8, 2024

Greenfield Notebook: May 8, 2024

West County Notebook: May 8, 2024

West County Notebook: May 8, 2024

Sports

High Schools: MacKenzie Paulin tosses one-hitter to lift Greenfield softball past Frontier

Back in April, the Frontier softball team handed Greenfield its first and only loss of the season thus far.The Green Wave got their revenge on Tuesday. MacKenzie Paulin limited the Redhawks to one hit, striking out 11 and only walking two, helping...

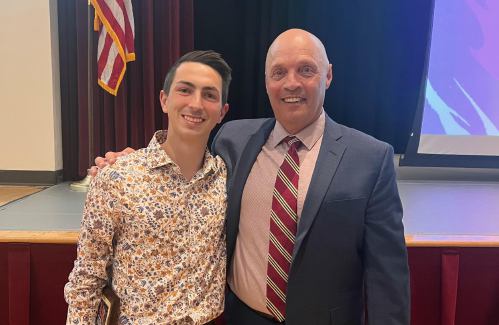

Bulletin Board: Bryce King wins Dean College men’s soccer’s Coaches Award

Bulletin Board: Bryce King wins Dean College men’s soccer’s Coaches Award

Opinion

My Turn: Freud — explorer of inner space

My mother often reminded me that “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread” — her words are one of those childhood memories that remain fixed in many a young brain, laid down in the synapses without our knowledge and long before we were capable of...

My Turn: We all deserve a break

My Turn: We all deserve a break

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Shirley and Mike Majewski: Vote for Blake Gilmore

Shirley and Mike Majewski: Vote for Blake Gilmore

Kathy Sylvester: Vote for expertise on May 6

Kathy Sylvester: Vote for expertise on May 6

Business

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

GREENFIELD — Three decades ago, Sean and Darren Pierce, two brothers in their mid-20s, decided to start selling coffee — a business venture that was funded by a roughly $30,000 mountain of credit card debt.Today, the Greenfield-based Fogbuster Coffee...

Goddard finds ‘best location’ in Shelburne Falls with new Watermark Gallery space

Goddard finds ‘best location’ in Shelburne Falls with new Watermark Gallery space

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

Arts & Life

Providing opportunity for people to grow: The United Arc of Franklin County’s annual Gardening with Steve event a highlight of spring

Steve McConley credits his wife, Doreen, for his interest in growing plants. Doreen brought solid gardening skills to their union, and Steve appreciates her encouragement. The McConleys have a garden at their Bernardston home, and now Steve shares...

Obituaries

Stephen Kozma

Stephen Kozma

Northfield, MA - Stephen Roy Kozma, 65, of Gill, Ma passed away unexpectedly at home on May 5, 2024. He was born in Greenfield, MA on Dec. 1, 1958 the eldest of five, to Stephen (deceased in 2014) and Marita (Bassett) Kozma.After gradua... remainder of obit for Stephen Kozma

Stephen A. Clark

Stephen A. Clark

Greenfield, MA - Stephen A. Clark, 76, of Greenfield, Massachusetts died Saturday April 27, 2024 at home. He was born in Brattleboro, VT on December 1, 1947, the son of Lloyd and Elizabeth (Rounds) Clark. Stephen was a graduate of Green... remainder of obit for Stephen A. Clark

Richard Powers

Richard Powers

Richard "Dick" Powers Northfield, MA - On May 2, 2024 Richard "Dick" "Dickie" Powers, 79, passed away at the home of his daughter, with his daughters by his side, following a long battle with vascular and frontotemporal dementia. He was ... remainder of obit for Richard Powers

Edwin J. Nartowicz

Edwin J. Nartowicz

Northampton, MA - Edwin J. Nartowicz, 100, of Northampton, passed away on Thursday, April 25, 2024, surrounded by his loving family at Cooley Dickinson Hospital. He was born in South Deerfield on November 7, 1923, to the late John and A... remainder of obit for Edwin J. Nartowicz

Work on Pinedale Avenue Bridge connecting Athol and Orange to resume

Work on Pinedale Avenue Bridge connecting Athol and Orange to resume

Pair of public servants vying for Selectboard seat in Heath

Pair of public servants vying for Selectboard seat in Heath

Lawyer argues Joshua Hart’s 2018 conviction for Orange murder had inconsistent verdicts

Lawyer argues Joshua Hart’s 2018 conviction for Orange murder had inconsistent verdicts

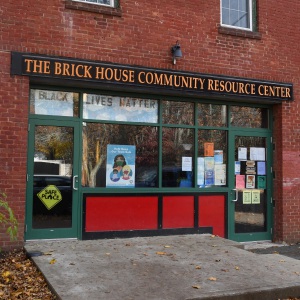

South County Senior Center opts not to renew church lease after rift over LGBTQ program

South County Senior Center opts not to renew church lease after rift over LGBTQ program

Moratoriums on large-scale solar, battery storage passed in Northfield

Moratoriums on large-scale solar, battery storage passed in Northfield

Boys volleyball: Carey twins help power Frontier past Belchertown in straight sets (PHOTOS)

Boys volleyball: Carey twins help power Frontier past Belchertown in straight sets (PHOTOS) Baseball: Logan Moore holds Smith Academy to one hit in Mohawk Trail’s 1-0 victory (PHOTOS)

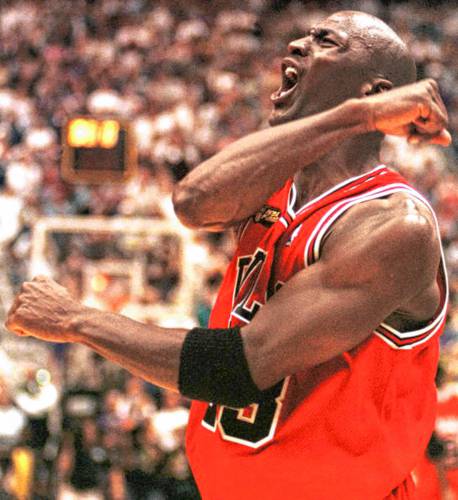

Baseball: Logan Moore holds Smith Academy to one hit in Mohawk Trail’s 1-0 victory (PHOTOS) Swayman stops 38 shots, Bruins roll past Panthers 5-1 for 1-0 series lead

Swayman stops 38 shots, Bruins roll past Panthers 5-1 for 1-0 series lead Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song

Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song The house that therapy built: Multimedia artist Lisa Winter to display “My House” at the Wendell Meetinghouse this Sunday

The house that therapy built: Multimedia artist Lisa Winter to display “My House” at the Wendell Meetinghouse this Sunday Fun Fest returns to Turners Falls: Música Franklin hosts 6th annual family-friendly, free event, May 11

Fun Fest returns to Turners Falls: Música Franklin hosts 6th annual family-friendly, free event, May 11 Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses

Valley Bounty: Delivering local food onto students’ plates: Marty’s Local connects farms to businesses