Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

SUNDERLAND — Police located a cabin in the woods around Clark Mountain Road Thursday afternoon that is believed to belong to Taaniel Herberger-Brown, the suspect accused of murdering a man at 92 Chapman St. in Greenfield and storing his body in a...

Frontier Regional School students appeal to lower voting age

When Sunderland residents head to their Annual Town Meeting on Friday, they’ll vote on the town’s budget, some bylaw changes and a citizen’s petition with a unique twist, as the residents who brought the article forward can’t actually vote on...

Sports

Track & field: Greenfield, Mohawk Trail split dual meet

It was a dual meet split for the Greenfield and Mohawk Trail track and field teams on Thursday.The Greenfield boys captured a 90-54 victory over the Warriors while the Mohawk Trail girls snagged a 123-18 victory over the Wave.Here are the winners from...

Country Club of Greenfield holding Youth Golf Camp June 24-27

Country Club of Greenfield holding Youth Golf Camp June 24-27

Opinion

My Turn: A moral justification for civil disobedience to abortion bans

Over the last several years, in response to abortion bans and restrictions, advocates around the country have developed an alternative supply network for abortion pills outside of the medical system and the law.As a lawyer and law-abiding citizen, I...

Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution on Iran

Guest columnist Rudy Perkins: Dangerous resolution on Iran

Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis

Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis

My Turn: April is second chance month

My Turn: April is second chance month

Business

Goddard finds ‘best location’ in Shelburne Falls with new Watermark Gallery space

SHELBURNE FALLS — The 20 Bridge St. space that formerly housed Molly Cantor’s pottery now displays Watermark Gallery’s eclectic collection of modern art pieces.Local artist Laurie Goddard opened Watermark Gallery last month as her seventh location in...

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Arts & Life

Sounds Local: A rock circus returns to Turners Falls: The Slambovian Circus of Dreams brings the fun Friday night at the Shea

The circus is coming to town, and not the kind with elephants and clowns. I’m talking about the Slambovian Circus of Dreams, a rock group from the Hudson Valley in New York that makes music as unique as its name. The band, which has frequently...

Obituaries

Dorothy Masterson Bennett

Dorothy Masterson Bennett

Conway, MA - Dorothy Masterson, the daughter of John Cochran Masterson and Dorothy Goodwin Masterson, was born January 15, 1932 in the Mary Alley Hospital on Franklin Street, Marblehead. She died April 20, 2024, age 92 years, in her bed... remainder of obit for Dorothy Masterson Bennett

Audrey McKemmie

Audrey McKemmie

Greenfield, MA - Audrey A. McKemmie of Greenfield and formerly of Amherst passed away on April 23, 2024, after a period of declining health. Born in Greenfield, December 12, 1930, she was the only child of John and Susie (Hayden) Kolink... remainder of obit for Audrey McKemmie

Reita G. Wheeler

Reita G. Wheeler

Colrain, MA - Reita G. (Sell) Wheeler, 77, of East Colrain Rd., passed away on Wednesday, April 24, 2024 at Baystate Franklin Medical Center in Greenfield. Reita was born in Westfield, MA on November 25, 1946 the daughter of Gustave... remainder of obit for Reita G. Wheeler

Constance Julia Dargis

Constance Julia Dargis

Constance Julia (LaMountain) Dargis Montague Center, MA - Constance "Connie" Julia Dargis, 98, formerly of Turners Falls MA, suffered an unexpected illness on November 13th and passed away peacefully on November 16, 2023 at the home of her ... remainder of obit for Constance Julia Dargis

Montague Cemetery Commission dedicating town’s first green burial site

Montague Cemetery Commission dedicating town’s first green burial site

Ethics Commission raps former Leyden police chief, captain for conflict of interest violations

Ethics Commission raps former Leyden police chief, captain for conflict of interest violations

Federal probe targets UMass response to anti-Arab incidents

Federal probe targets UMass response to anti-Arab incidents

New Salem event will turn gun parts into gardening tools, jewelry

New Salem event will turn gun parts into gardening tools, jewelry

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Sunderland Public Library hosting 20th birthday party for its building

Sunderland Public Library hosting 20th birthday party for its building

Real Estate Transactions: April 26, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: April 26, 2024

Shelburne fair to explore energy-efficient options for homeowners

Shelburne fair to explore energy-efficient options for homeowners

Erving rejects trade school’s incomplete proposal for mill reuse

Erving rejects trade school’s incomplete proposal for mill reuse

Montague Notebook: April 24, 2024

Montague Notebook: April 24, 2024 Monroe election sees no contests, some positions without candidates

Monroe election sees no contests, some positions without candidates Business Briefs: April 26, 2024

Business Briefs: April 26, 2024 PHOTO: Spectacular spire

PHOTO: Spectacular spire High schools: Amy Mihailicenco, Greenfield girls tennis edge Turners Falls (PHOTOS)

High schools: Amy Mihailicenco, Greenfield girls tennis edge Turners Falls (PHOTOS) Softball: Turners edges Tech, Greenfield’s Paulin notches 100th hit, Mahar win first game since 2019

Softball: Turners edges Tech, Greenfield’s Paulin notches 100th hit, Mahar win first game since 2019 High schools: Lilly Ross records 100th career hit in Franklin Tech’s win over Northampton

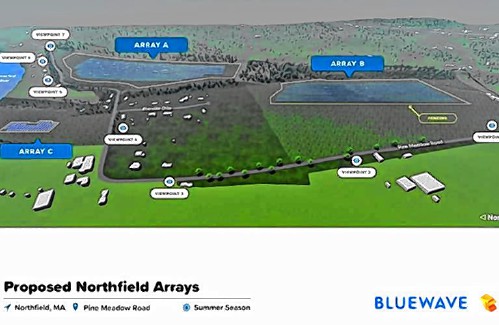

High schools: Lilly Ross records 100th career hit in Franklin Tech’s win over Northampton My Turn: Industrial solar installations are overwhelming Northfield neighborhood

My Turn: Industrial solar installations are overwhelming Northfield neighborhood New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Rescuing food and feeding people: Rachel’s Table programs continue to expand throughout western Mass

Rescuing food and feeding people: Rachel’s Table programs continue to expand throughout western Mass A day to commune with nature: Western Mass Herbal Symposium will be held May 11 in Montague

A day to commune with nature: Western Mass Herbal Symposium will be held May 11 in Montague Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever

Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28