Latest News

Battery storage bylaw passes in Wendell

Battery storage bylaw passes in Wendell

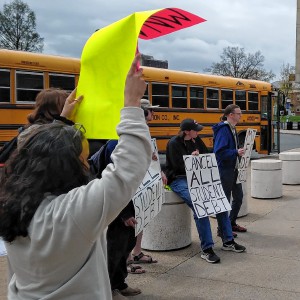

Debt-burdened UMass students, grads rally for relief

Debt-burdened UMass students, grads rally for relief

Real Estate Transactions: May 3, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: May 3, 2024

1989 homicide victim found in Warwick ID’d through genetic testing, but some mysteries remain

GREENFIELD — It took nearly 35 years, but the human remains found just off Route 78 in Warwick in 1989 have been identified as belonging to Constance (Holminski) Bassignani, who was 65 years old at the time of her murder.The Northwestern District...

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

GREENFIELD — Three decades ago, Sean and Darren Pierce, two brothers in their mid-20s, decided to start selling coffee — a business venture that was funded by a roughly $30,000 mountain of credit card debt.Today, the Greenfield-based Fogbuster Coffee...

Most Read

Editors Picks

Business Briefs: May 3, 2024

Business Briefs: May 3, 2024

PHOTOS: Welcome, May

PHOTOS: Welcome, May

PHOTOS: Making an impression

PHOTOS: Making an impression

Greenfield Notebook: May 2, 2024

Greenfield Notebook: May 2, 2024

Sports

Softball: Pioneer pulls ahead late to defeat Northampton, 34-29 (PHOTOS)

Trailing Northampton 12-2 after one inning, the Pioneer softball team knew it needed to put runs up in a hurry to get back in the game. The Panthers did just that. Pioneer cut the lead to 15-11 after four before erupting for 14 runs in the sixth...

High Schools: Sixth inning rally lifts Pioneer baseball past Greenfield, 4-3

High Schools: Sixth inning rally lifts Pioneer baseball past Greenfield, 4-3

Bulletin Board: Rodney Demers sinks ace at Thomas Memorial

Bulletin Board: Rodney Demers sinks ace at Thomas Memorial

Opinion

Guest columnist Gene Stamell: We know what we know

Columnist’s note: The following contains many parenthetical asides and seemingly unimportant details that somehow, one hopes, lead to a conclusion that the reader finds moderately interesting or entertaining or, at the very least, bearable. Once...

Michelle Caruso: Questions candidate’s judgment after 1980s police training incident

Michelle Caruso: Questions candidate’s judgment after 1980s police training incident

Shirley and Mike Majewski: Vote for Blake Gilmore

Shirley and Mike Majewski: Vote for Blake Gilmore

Kathy Sylvester: Vote for expertise on May 6

Kathy Sylvester: Vote for expertise on May 6

Bernie Sadoski: Blake Gilmore is committed to his community

Bernie Sadoski: Blake Gilmore is committed to his community

Business

Goddard finds ‘best location’ in Shelburne Falls with new Watermark Gallery space

SHELBURNE FALLS — The 20 Bridge St. space that formerly housed Molly Cantor’s pottery now displays Watermark Gallery’s eclectic collection of modern art pieces.Local artist Laurie Goddard opened Watermark Gallery last month as her seventh location in...

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Arts & Life

Sounds Local: Broadway star returns to Greenfield for concert: Kevin Duda to sing with Franklin County Community Chorus this Sunday

There’s nothing like the powerful sound of voices joining together in song, and you can experience that when The Franklin County Community Chorus celebrates its 10th anniversary with a concert on Sunday, May 5, at 3 p.m. at the Greenfield High School...

Sharing the gift of spring: The tradition of making May Baskets for May Day

Sharing the gift of spring: The tradition of making May Baskets for May Day

Obituaries

Candace Loughrey

Candace Loughrey

Northfield, MA - Candace Bleakley Loughrey, of Old Turnpike Road in Northfield, died April 25 at Fisher Home Hospice in Amherst after a valiant struggle following a stroke. She was 77. She was born May 27, 1946, along with her twin sist... remainder of obit for Candace Loughrey

Jennifer M. Read

Jennifer M. Read

South Deerfield, MA - Jennifer Read of South Deerfield, beloved wife and mother, died peacefully on April 21, 2024 at the age of 79 after a long struggle with Alzheimer's disease. Jennifer was born on January 1, 1945 at Brooklyn Naval ... remainder of obit for Jennifer M. Read

Candance Loughrey

Candance Loughrey

Northfield, MA - Candace Bleakley Loughrey, of Old Turnpike Road in Northfield, died April 25 at Fisher Home Hospice in Amherst after a valiant struggle following a stroke. She was 77. She was born May 27, 1946, along with her twin sist... remainder of obit for Candance Loughrey

Robert A. York

Robert A. York

Greenfield, MA - Robert A. York passed away peacefully on April 24, 2024 at his home in Greenfield, MA, surrounded by his wife and children. He was 77 years old. Bob had been battling 5 unrelated cancers since 2008. He was born on Febru... remainder of obit for Robert A. York

Short-term rental bylaw tops Buckland Town Meeting warrant

Short-term rental bylaw tops Buckland Town Meeting warrant

World Labyrinth Day event in Greenfield to promote unity, peace

World Labyrinth Day event in Greenfield to promote unity, peace

Selectboard race between Gilmore, Shores Ness tops Deerfield ballot

Selectboard race between Gilmore, Shores Ness tops Deerfield ballot

Inaugural Cultural Kaleidoscope event at Frontier helps students become global citizens

Inaugural Cultural Kaleidoscope event at Frontier helps students become global citizens

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Office of Travel and Tourism director tours Franklin County, looks to increase presence

Office of Travel and Tourism director tours Franklin County, looks to increase presence

Softball: Greenfield puts up 9-spot in the 8th inning to knock off rival Turners 11-2 in extra-inning thriller (PHOTOS)

Softball: Greenfield puts up 9-spot in the 8th inning to knock off rival Turners 11-2 in extra-inning thriller (PHOTOS) Softball: Franklin Tech's Hannah Gilbert records 100th career hit in win over Pioneer

Softball: Franklin Tech's Hannah Gilbert records 100th career hit in win over Pioneer New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Tips for planning a successful garden: Creating a healthy garden is all about maintaining good habits

Tips for planning a successful garden: Creating a healthy garden is all about maintaining good habits Speaking of Nature: Bird of my dreams, it’s you: Spotting a White-tailed Tropicbird on our cruise in Bermuda

Speaking of Nature: Bird of my dreams, it’s you: Spotting a White-tailed Tropicbird on our cruise in Bermuda Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how