Local researchers advocate for increased roles for citizen science

| Published: 04-21-2023 5:19 PM |

Among the lush hardwoods of Massachusetts’ forests and babbling brooks, volunteers with a keen interest in science trek through to check their trail cameras.

These researchers review the footage for signs of black bears, which is used to track their whereabouts throughout the state. It’s all in a day’s work for residents participating in citizen science

Citizen science, also known as community science, refers to public participation in scientific research, specifically in data collection and analysis. Citizen science projects include collecting water samples, counting butterflies or classifying galaxies.

Research projects that use volunteers traditionally limit amateur scientists to data collection work, while the professionals plan the procedures, ask investigative questions and spearhead data analysis and discussion. However, academics who study the social impacts of science and technology view this separation as a missed opportunity.

Conservation and environmental research projects in western Massachusetts practice citizen science with varying levels of community participation. While large organizations such as Native Plant Trust use community science for rigorous data collection, smaller nonprofits like the Greenfield-based Connecticut River Conservancy and Amherst College’s MassMammals experiment with community engagement throughout the scientific process.

Native Plant Trust is a conservation nonprofit that concentrates on native New England plants. The organization’s database documents more than 800 plant species in Franklin County alone. With thousands of plants from each state to monitor, its Plant Conservation Volunteer Program enlists volunteers to find, analyze and map rare species.

“By greatly increasing our impact on the landscape, [surveyors] contribute thousands of hours of in-time support to collect this data for understanding and protecting these rare plant species,” said Native Plant Trust’s Botanical Coordinator Micah Jasny.

Surveyors record species-specific diagnostic information, the number and physical traits of plants present, and any threats. They take photos, organize notes and create maps. All that data is submitted to Native Plant Trust to compile and is later shared with state governments to inform conservation policies and decisions. Like many citizen science programs, volunteers cannot analyze or access data unless they double as a scientific researcher.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

Real Estate Transactions: May 10, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: May 10, 2024

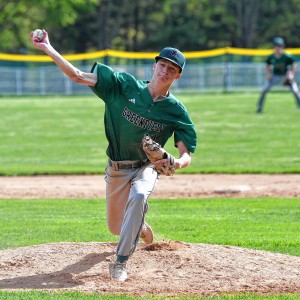

Baseball: Caleb Thomas pitches Greenfield to first win over Frontier since 2019 (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Caleb Thomas pitches Greenfield to first win over Frontier since 2019 (PHOTOS)

High Schools: Greenfield softball squeaks out 1-0 win over Franklin Tech in pitchers duel between Paulin, Gilbert

High Schools: Greenfield softball squeaks out 1-0 win over Franklin Tech in pitchers duel between Paulin, Gilbert

Volunteers include students, home gardeners interested in native plant species, hobbyists who are passionate about native plants and professional botanists. Jasny noted the passion of surveyors, citing how volunteers have hiked miles into the White Mountains to investigate a single species.

Connecticut River Conservancy, however, publishes citizen science data online. The organization offers five volunteer-based programs, but only the water quality and migratory fish monitoring fall under community science, rather than conservation work.

“We do our best to involve the community as much as we can by bringing them along with us and helping them essentially lead the efforts, making this a very volunteer-led community science program,” Connecticut River Conservancy Ecology Planner Aliki Fornier said. “And then there are the other ones that are more based on, you know, applied science that do involve data gathering.”

Science and technology studies academics note that volunteer-based participation limits involvement of community members because only people with extra time in their work schedule can commit to training and data gathering. Fornier, who recruits volunteers for community science projects, noted that most of the volunteers are retired elders, students from schools in affluent communities, and people with existing knowledge about and experience with the Connecticut River.

While the Connecticut River Conservancy addresses who is conducting citizen science, a mammal documentation program from Amherst College investigates how to conduct citizen science. MassMammals tracks the distribution and population density of foxes, deer, bobcats and other mammals across the state using citizen-reported sightings and trail cameras.

The Amherst College biology department developed the program as an offshoot of MassBears, a research project that identifies and locates black bears. Data for the project can range from animal tracks, hair samples and photos or videos of the animals.

Thea Kristensen, biology laboratory coordinator at Amherst College, began MassMammals after the pandemic halted lab work and data collection. Previously, Kristensen and her students compiled hair samples to analyze the DNA of each bear and document the black bear population. Students in the MassMammals project subsequently turned to citizen science to supplement the hair data and continue working on the project from home.

Since its founding, MassMammals has expanded citizen science beyond data collection. Kristensen said undergraduate students in the research project set up trail cameras with elementary, middle and high school students. The K-12 students monitor the cameras and send their data back to Amherst College’s MassMammals lab to organize. But it’s the young students and teachers who draw conclusions with the wildlife data, not professional scientists. Schools they’ve worked with include: Northampton Public Schools, Amherst-Pelham Regional Public Schools, Tantasqua Regional Senior High School, Mohawk Trail Regional School, Leverett Elementary School, Lander Grinspoon Academy, Quabbin Regional High School and Hatfield Elementary.

“My students felt a really wonderful relationship with the teachers,” Kristensen said, “and the teachers were able to help us figure out what are teachers looking for, what would be beneficial to be able to come up with lessons that are connected to state standards … but also giving [younger] students the opportunity to engage in science and be scientist.”

Kristensen found the MassMammals program’s collaboration with schools improved her undergraduate students’ scientific communication and confidence as a scientist. However, the project also effectively engages K-12 students in the scientific process.

The next step for the MassMammals project involves community members posing questions of inquiry and then working to find answers.

“I think that one of the central components of community science is to be able to make science accessible to everyone and to invite them to the process,” Kristensen said. “So now that we have that kind of traction and success in making these partnerships with our community, it gives us the opportunity to say, ‘OK, let’s work with you and figure out what are your questions and try to pursue those.’”

Deerfield’s Tilton Library expansion ‘takes a village’

Deerfield’s Tilton Library expansion ‘takes a village’ UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor

UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor Four Rivers Climate Club organizes litter cleanup, panel on environmental activism

Four Rivers Climate Club organizes litter cleanup, panel on environmental activism