Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

GREENFIELD — The Northwestern District Attorney’s Office has identified Christopher Hairston, 35, last known to reside in Pittsfield, as the victim found dismembered in a barrel in a Chapman Street apartment on Monday evening.Suspect Taaniel...

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

State regulators suspended Northfield EMS Chief and Orange EMS Capt. Mark Fortier’s paramedic license over his alleged failure to properly assess a 2-week-old infant during a house call and for refusing the child transportation in an ambulance,...

Most Read

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

Greenfield man arrested in New York on murder charge

Greenfield man arrested in New York on murder charge

Man allegedly steals $100K worth of items from Northampton, South Deerfield businesses

Man allegedly steals $100K worth of items from Northampton, South Deerfield businesses

Joannah Whitney of Greenfield wins 33rd annual Poet’s Seat Poetry Contest

Joannah Whitney of Greenfield wins 33rd annual Poet’s Seat Poetry Contest

Editors Picks

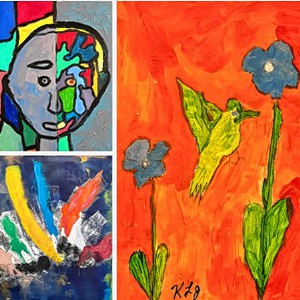

Self-expression on display: ServiceNet members’ artworks on view at Greenfield Public Library through end of May

Self-expression on display: ServiceNet members’ artworks on view at Greenfield Public Library through end of May

PHOTOS: Literary insight

PHOTOS: Literary insight

Dog of the Week: Carson

Dog of the Week: Carson

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Sports

High schools: Seventh-inning rally helps Turners Falls softball edge Frontier 6-3 (PHOTOS)

The middle portion of a huge three-day stretch for the Turners Falls softball team saw the Thunder save their best for last on Friday.Trailing 3-1 entering the top of the seventh inning against Frontier, Janelle Massey clubbed a game-tying two-run...

Keeping Score with Chip Ainsworth: Minutemen ready for their spring formal

Keeping Score with Chip Ainsworth: Minutemen ready for their spring formal

Track & field: Greenfield, Mohawk Trail split dual meet

Track & field: Greenfield, Mohawk Trail split dual meet

Opinion

My Turn: Dear Patients — We hear you!

As a family practitioner and the medical director of Valley Medical Group, I care deeply about my patients and our community. During my 20 years of practicing full-spectrum primary care in Franklin County, I have come to value the relationships I...

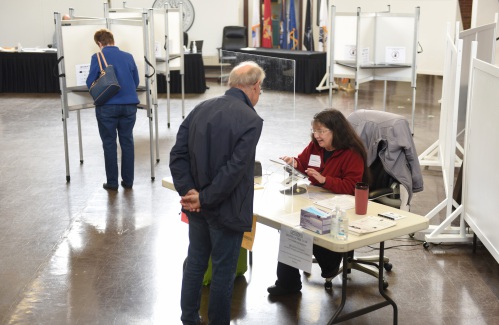

Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield

Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield

Ava Gips: Carolyn Shores Ness gets things done

Ava Gips: Carolyn Shores Ness gets things done

Guest columnist Jonathan Kahane: Clapping back at no-good scammers

Guest columnist Jonathan Kahane: Clapping back at no-good scammers

Brenda Davies: Makes some healthy changes for our planet

Brenda Davies: Makes some healthy changes for our planet

Business

Goddard finds ‘best location’ in Shelburne Falls with new Watermark Gallery space

SHELBURNE FALLS — The 20 Bridge St. space that formerly housed Molly Cantor’s pottery now displays Watermark Gallery’s eclectic collection of modern art pieces.Local artist Laurie Goddard opened Watermark Gallery last month as her seventh location in...

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Arts & Life

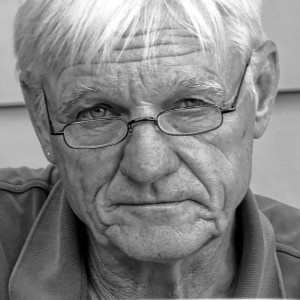

Proof that it’s never too late: Solo exhibit and free workshops honor the late Frederick Gao, a Belchertown resident who became a painter in his last five years

For the months of May and June, the Sunderland Public Library’s Lane Family Reading Room Gallery will turn into a fount of inspiration, as the library honors the work of a late-blooming artist.Through “Awing & Honoring Frederick Gao,” the library will...

Obituaries

Dorothy Masterson Bennett

Dorothy Masterson Bennett

Conway, MA - Dorothy Masterson, the daughter of John Cochran Masterson and Dorothy Goodwin Masterson, was born January 15, 1932 in the Mary Alley Hospital on Franklin Street, Marblehead. She died April 20, 2024, age 92 years, in her bed... remainder of obit for Dorothy Masterson Bennett

Audrey McKemmie

Audrey McKemmie

Greenfield, MA - Audrey A. McKemmie of Greenfield and formerly of Amherst passed away on April 23, 2024, after a period of declining health. Born in Greenfield, December 12, 1930, she was the only child of John and Susie (Hayden) Kolink... remainder of obit for Audrey McKemmie

Reita G. Wheeler

Reita G. Wheeler

Colrain, MA - Reita G. (Sell) Wheeler, 77, of East Colrain Rd., passed away on Wednesday, April 24, 2024 at Baystate Franklin Medical Center in Greenfield. Reita was born in Westfield, MA on November 25, 1946 the daughter of Gustave... remainder of obit for Reita G. Wheeler

Constance Julia Dargis

Constance Julia Dargis

Constance Julia (LaMountain) Dargis Montague Center, MA - Constance "Connie" Julia Dargis, 98, formerly of Turners Falls MA, suffered an unexpected illness on November 13th and passed away peacefully on November 16, 2023 at the home of her ... remainder of obit for Constance Julia Dargis

McGovern, Gobi visit development sites in Greenfield, Wendell

McGovern, Gobi visit development sites in Greenfield, Wendell

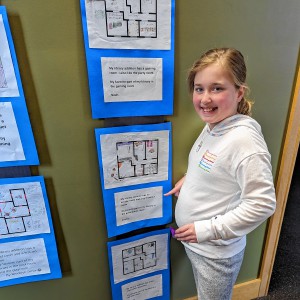

Turners Falls third graders share vision for new or expanded library

Turners Falls third graders share vision for new or expanded library

The World Keeps Turning: Quantifying happiness — How we measure up

The World Keeps Turning: Quantifying happiness — How we measure up

Vehicle replacements, petition on tax rate on tap for Bernardston Town Meeting

Vehicle replacements, petition on tax rate on tap for Bernardston Town Meeting

Personnel bylaw, tax bill change on Deerfield Town Meeting warrant

Personnel bylaw, tax bill change on Deerfield Town Meeting warrant

What are the protocols for emergency transport of infants?

What are the protocols for emergency transport of infants?

Hawley selling military dump truck

Hawley selling military dump truck

Beacon Hill Roll Call: April 15 to April 19, 2024

Beacon Hill Roll Call: April 15 to April 19, 2024

Montague Cemetery Commission dedicating town’s first green burial site

Montague Cemetery Commission dedicating town’s first green burial site

High schools: Amy Mihailicenco, Greenfield girls tennis edge Turners Falls (PHOTOS)

High schools: Amy Mihailicenco, Greenfield girls tennis edge Turners Falls (PHOTOS) Softball: Turners edges Tech, Greenfield’s Paulin notches 100th hit, Mahar win first game since 2019

Softball: Turners edges Tech, Greenfield’s Paulin notches 100th hit, Mahar win first game since 2019 New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week Sounds Local: A rock circus returns to Turners Falls: The Slambovian Circus of Dreams brings the fun Friday night at the Shea

Sounds Local: A rock circus returns to Turners Falls: The Slambovian Circus of Dreams brings the fun Friday night at the Shea Rescuing food and feeding people: Rachel’s Table programs continue to expand throughout western Mass

Rescuing food and feeding people: Rachel’s Table programs continue to expand throughout western Mass A day to commune with nature: Western Mass Herbal Symposium will be held May 11 in Montague

A day to commune with nature: Western Mass Herbal Symposium will be held May 11 in Montague