Educators float MCAS alternatives should voters opt to ditch test as a graduation requirement

| Published: 01-09-2024 5:43 PM |

Opponents of using the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) test as a high school graduation requirement suggest there are better ways to measure student achievement, should voters get an opportunity to remove the requirement in November.

Last September, Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Campbell ruled the proposed 2024 ballot question to remove the MCAS graduation requirement for high school students was legally sound.

The question, strongly supported by the Massachusetts Teachers Association, would only remove the requirement, which has been in place since 2003, though students would still have to take the exam. Lawmakers could approve the change, or backers of the initiative would need to collect additional signatures to place it on the ballot.

Test supporters, particularly in the business community, stress that the exam, while in need of revisions, is the primary means for providing students, families, educators and policymakers with objective, valid, reliable and comparable information essential to determining gaps in educational outcomes. It also helps determine preparedness for college and career success, and identifies where additional resources are most needed — especially for those who have been and continue to be systemically marginalized: students of color, those with disabilities, English learners and students from low-income families, supporters argue.

The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, which oversees the testing, says “MCAS has been upgraded to better measure the critical skills students need for success in the 21st century: deeper understanding, knowledge application, synthesizing and writing. Most students will take the test on a computer reflecting the digital world we live in today. MCAS helps the commonwealth identify schools and districts that need additional support.”

But many scholars criticize the test as a whole, arguing that it provides students with no educational value and should be eliminated altogether. They recommend assessments that test how students apply what they learn in the classroom.

Lifelong educators like Harry Feder, executive director of Fair Test, which supports the implementation of “multiple, non-biased measures of student achievement,” said MCAS tests memorization skills and knowledge of formulas rather than critical thinking and real-world skills. Teachers often have to stray from their curriculum when preparing students to take the MCAS.

“There’s a lot of complaints about … the issue of the narrowing of curriculum. What does MCAS actually test?” Feder asked.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

Real Estate Transactions: May 10, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: May 10, 2024

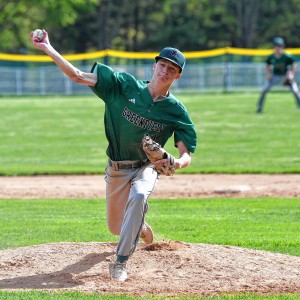

Baseball: Caleb Thomas pitches Greenfield to first win over Frontier since 2019 (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Caleb Thomas pitches Greenfield to first win over Frontier since 2019 (PHOTOS)

High Schools: Greenfield softball squeaks out 1-0 win over Franklin Tech in pitchers duel between Paulin, Gilbert

High Schools: Greenfield softball squeaks out 1-0 win over Franklin Tech in pitchers duel between Paulin, Gilbert

Feder also cited the widely researched “disproportionate discriminatory impact” MCAS has on students of color and low-income students, who do more poorly on the test overall.

Jack Schneider, author of “Beyond the Test Scores: A Better Way to Measure School Quality” and professor of education at University of Massachusetts Amherst, said another major issue with MCAS is that it takes away from physical time in the classroom and contributes to chronic absenteeism.

“We know right now that standardized testing is really disruptive. There are ways of minimizing that disruption,” Schneider said. “For instance, we don’t need to test every single student in grades three through eight as well as 10th grade every single year in order to get basically the same information.”

Beyond that, MCAS has a history of controversial questions. In 2019, students and teachers advocated for the removal of a question that asked students to “write from the perspective of an ‘openly racist’ character in the novel ‘The Underground Railroad,’” according to WBUR.

At the time, MTA President Merrie Najimy said all tests taken that included the racist question should be nullified because it was likely that the offensive nature of the question affected students’ test results.

Mary Battenfeld, clinical professor of American studies at Boston University with a focus on contemporary education policy and parent advocacy, said many of the problems with MCAS can be traced to the Education Reform Act.

The 1993 bill aimed to improve “accountability” on behalf of schools, a response to widespread panic at the release of a report titled “A Nation at Risk,” which suggested that education in the country was suffering because SAT scores were decreasing.

Battenfeld said that “A Nation at Risk” was “based on bad data.”

As schools across the state continued to desegregate in the 1960s and more money was funneled into education under former President Lyndon B. Johnson, a more diverse pool of students were taking the SAT.

“The data was saying, [SAT scores are] dropping, but they actually were rising if you took into account incremental rises over time,” she said.

Battenfeld said the same flawed methods of evaluating test scores are used today.

For example, when MCAS was administered for the first time following the COVID-19 pandemic, WBUR reported that the 2022 scores were “less than reassuring,” indicating a “slow and mixed recovery.”

However, Battenfeld said these statistics made sense from a holistic perspective, considering pandemic-incited learning loss.

“If you’re only looking at the end line of what the score is … you’re not looking at improvement,” she said.

While some MCAS supporters argue that it is a crucial tool to rank schools in the state and has helped Massachusetts reach its high national ranking in education, Schneider said this is not the case.

Companies like Niche and U.S. News & World Report, which are known for ranking schools, “are completely blind to what is happening inside schools, making their rankings essentially meaningless,” he said.

“Everybody knows at this point that if you just are looking at proficiency rates on standardized tests, you’re not learning about school quality,” Schneider said. “[What] you’re learning about is the affluence of the community.

“These aren’t ratings of school quality; these are ratings of privilege and disadvantage,” Schneider added.

Though some MCAS supporters argue that the test is necessary to rank Massachusetts education on a national level, Schneider said the Nation’s Report Card, an annual report from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, already does that.

NAEP uses matrix testing, in which they randomly sample students from a variety of grades and schools to measure a state’s progress, a method that significantly reduces classroom disruption, according to Schneider.

Citizens for Public Schools reports that the idea that accountability through MCAS is what previously allowed the state to rise in national ranking is false.

“Massachusetts was long at or near the top on the long-standing national test known as NAEP, before the MCAS and state standards came along,” they wrote. “This was mostly because we have a relatively affluent and educated state, two things that are closely linked to test results.”

According to Schneider, who leads sister organizations Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment and the Education Commonwealth Project, alternative methods of testing are already in the works. Together, these organizations have built guidelines to what they call “classroom embedded assessments,” which test students’ ability to apply what they learn in the classroom.

Schneider hopes that through assigned application projects, evaluated by teachers, students will be able to feel the value of their work.

“If you ask any students in the commonwealth of Massachusetts, right after they take MCAS, what they felt the value of that was, you have a very high likelihood that you are going to hear a student say, ‘I didn’t see any value in that,’” Schneider said.

A crucial goal of classroom embedded assessment, according to Schneider, is its ability to provide teachers with valuable feedback on what works and what doesn’t work in the classroom.

“Sometimes, people will make the case that what we learn from standardized assessments helps school leaders and educators adjust their practice. And that just simply isn’t true,” he said. “The information just isn’t timely enough, and isn’t granular enough to really be valuable for the purpose of informing instruction.”

Feder said he has already seen some school districts in the commonwealth adopt innovative testing methods.

“I think there are at least eight districts around the state that do [performance-based assessments] at all levels of schools, so not just high school. And those are both sort of summative assessments and formative assessments,” he said.

Schneider said that adopting innovative testing methods throughout the state is “well within the realm of possibility.”

“I think we have demonstrated that it is possible to do this now if you want to do it,” he said. “You would need the state to take this seriously and to use the resources that the state has at its disposal.”

Eden Mor writes for the Greenfield Recorder from the Boston University Statehouse Program.

Montague Notebook: May 10, 2024

Montague Notebook: May 10, 2024 Deerfield’s Tilton Library expansion ‘takes a village’

Deerfield’s Tilton Library expansion ‘takes a village’ UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor

UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor