Bill targets underenrollment disparities in AP courses

Kristen Hengtgen, senior policy analyst at the Education Trust, discusses a new policy brief she co-authored about boosting student participation in advanced coursework on Tuesday. ALISON KUZNITZ/STATE HOUSE NEWS SERVICE

| Published: 01-31-2024 4:53 PM |

BOSTON — Aiming to strengthen participation in advanced classes among Black and Latino high school students, lawmakers sought to build momentum Tuesday for a framework that would streamline how public colleges accept AP credits.

Redrafted legislation (H 4265), reported favorably out of the Joint Committee on Higher Education last week, would require all state colleges to implement a consistent standard for accepting AP exam scores of a 3 or higher to receive course credit. Similar policies are already in place in three dozen states, according to the College Board, which oversees the SAT and AP programs.

The bill is not heading straight to the House for a vote though, as it’s been shipped first to another committee — House Ways and Means.

Sens. Adam Gomez and Michael Moore, who sponsored earlier versions of the proposal, urged their colleagues to address persistent racial disparities in the number of Black and Latino students taking advanced courses, even as Massachusetts ranked first in the country for having the highest percentage of graduating seniors who scored at least a 3 on AP exams in 2021 and 2022.

Calling the bill a critical tool for improving equity and transparency in the education system, Moore said, “The only question is, how long do we wait to bring commonsense advanced course credit policies to our hardworking students?”

Sixty-four percent of all students completed at least one advanced course in 2021-2022, compared to only half of Latino students and just over half of Black students, Gomez and Moore said, as they cited research released Tuesday by the Education Trust, a national nonprofit that works to close opportunity gaps. Beyond AP classes, advanced coursework in Massachusetts also covers International Baccalaureate and dual enrollment programs.

“This disparity simply cannot be ignored,” Gomez said at a briefing hosted by the Education Trust and Mass Insight Education & Research, a nonprofit focused on advancing equity in K-12 education.

“Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that Black and Latino students comprise almost one-third of all public school students, yet they represent only 18% of AP test takers,” the Springfield Democrat said. “This imbalance is primarily attributed to various factors, such as a lack of support for these students to feel adequately prepared for the test and the financial barrier posed by AP exam fees.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

Real Estate Transactions: May 10, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: May 10, 2024

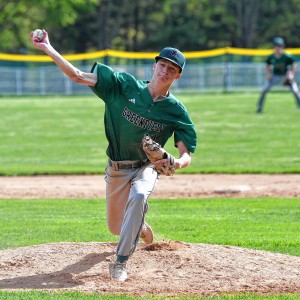

Baseball: Caleb Thomas pitches Greenfield to first win over Frontier since 2019 (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Caleb Thomas pitches Greenfield to first win over Frontier since 2019 (PHOTOS)

High Schools: Greenfield softball squeaks out 1-0 win over Franklin Tech in pitchers duel between Paulin, Gilbert

High Schools: Greenfield softball squeaks out 1-0 win over Franklin Tech in pitchers duel between Paulin, Gilbert

To improve equitable enrollment in AP classes, the Education Trust recommends mandating that colleges and universities be more transparent and consistent in how they award college credit, requiring and supporting school districts to expand eligibility for advanced courses, recruiting and retaining AP teachers of color, ensuring state data collection and sharing efforts, and eliminating barriers to advanced courses like exam fees.

Schools where the majority of students are Black or Latino are “much less likely” to offer AP courses compared to majority-white schools, according to the Education Trust’s brief. That aligns with national trends, said Kristen Hengtgen, a senior policy analyst at the Education Trust who co-authored the brief.

A patchwork of rules for handling AP test scores exists at Massachusetts public colleges and universities, with some accepting a passing score of a 3, with others demanding higher scores or not taking any AP credits, lawmakers and Hengtgen said. The AP tests are scored 1 to 5.

Research shows that students who earn a passing score perform well in college, take more classes tied to their AP disciplines, and are more likely to graduate in four years, the brief said.

About half of Latino students and 61% of Black students scored a 3 on AP tests in 2021-2022, Hengtgen said.

“If the state does not have a standardized credit policy that accepts 3s in all their institutions of higher education, Black and Latino students are disproportionately left out of getting and taking the credits that they deserved and earned,” Hengtgen said.

Coming into college with 10 hours of AP credit can reduce average student debt by $1,000, which is critical for Black and Latino students who have higher student loan burdens, according to the brief.

“I can also tell you as a parent who saw both of his children take advantage of AP courses, and see how that was able to help them when they entered college on reducing some of their credit burden, it’s so beneficial,” Moore said.

He added, “Many Black and Latino students attend schools that don’t have the same resources as their white counterparts, resulting in smaller focus on AP exam preparation, for less support for students who just need a little extra push to reach their educational potential. These students may also come from economically disadvantaged households, making it a heavier lift to afford the fees required.”

Deerfield’s Tilton Library expansion ‘takes a village’

Deerfield’s Tilton Library expansion ‘takes a village’ UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor

UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor Four Rivers Climate Club organizes litter cleanup, panel on environmental activism

Four Rivers Climate Club organizes litter cleanup, panel on environmental activism