Speaking of Nature: Hidden in plain sight: An Ovenbird makes a late-season appearance

This ovenbird finally popped out into the open and posed for a photo on a beautiful September morning. The stripe of orange feathers on top of the head is the diagnostic field mark that identifies the species. PHOTO BY BILL DANIELSON

| Published: 10-01-2023 10:38 PM |

October has arrived and I find myself taken by surprise. The forest behind my house is showing spots of fall colors and this appears to have happened all at once. I am certain that it has been a gradual process, but when one is distracted by the demands of work and family, it is possible for the little details to go unnoticed, despite the fact that they are right out in the open for all to see. By the time you read this column I am quite certain that fall foliage season will be in full swing.

Looking back at September I had several accomplishments that I believe are noteworthy. I managed to record photos 20,000 and 21,000 in the same month because I have remained determined to squeeze in as much exposure to nature as I possibly can before the increasing cold renders the notion of sitting motionless in an Adirondack chair for two-to-three hours untenable. As of the time this column was written, I was just one species away from tying the all-time record for the number of bird species observed in the month of September. If the weather cooperates, then I may have good news to share with you next week.

But for now, I want to share the story of my encounters with a surprise guest that made several appearances during my many birdwatching endeavors in the month of September. The hardcore birders in the audience may not find this species to be anything out of the ordinary, but as far as I know this is the first year that I have seen an Ovenbird (Seiurusaurocapilla) so late in the year. I believe this account will also point to the value of going to the same place over and over, so that one might pick up on the subtle changes that occur from one day, or one week, to the next.

Early in the month of September, when the migration season was starting to ramp up, there was a particular morning that seemed especially “birdy.” Black-throated green warblers, Magnolia warblers and even a rare Northern Parula were spotted in the thick vegetation at the edge of my meadow, but among them was an Ovenbird. This is a little warbler that has a lifestyle so distinctive from the other members of its group that its common name doesn’t even include the word warbler.

At a full six-inches in length, the Ovenbird is a bit larger than other members of the diminutive wood warbler group. This bird shows no sexual dimorphism, which means that adult males and females have the same coloration. A human cannot tell the sexes apart, but to the more discriminating eyes of the Ovenbirds themselves, there must be some difference that we are unaware of.

Another thing that you will notice about this species is the fact that there is none of that diabolical yellow-green in the feathers that makes many warblers difficult to identify in the fall. In fact, when I first spotted this bird I thought I might be looking at a thrush of some sort because of the prominent black spots on the white breast feathers. This was the field mark that first caught my eye and it wasn’t until I looked at the bird through the large telephoto lens on my camera that I was able to see the details of the head. That mohawk of orange feathers put any notion of a thrush into the bin.

This species was named “Ovenbird” because of the nest it builds. Contrary to what many of us might predict, the Ovenbird builds its nest on the ground. This is a vulnerable location that seems to ignore the fact that birds can fly, but it clearly works. However, the nature of the nest may hint at the fact that even the birds themselves realize that nesting on the ground is a risky prospect. The nest is built right out in the open on the floor of a forest dominated by deciduous trees. The nest is cup-shaped and made of predictable materials like dried grasses, mosses and other vegetation. Adding to the warmth and comfort of the eggs and chicks, the nest is often lined with soft hair collected from animals in the forest.

What makes the nest extraordinary is the fact that it comes complete with a dome made of leaves. When complete, the nest is virtually invisible, save for the comings and goings of the brooding female.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

1989 homicide victim found in Warwick ID’d through genetic testing, but some mysteries remain

1989 homicide victim found in Warwick ID’d through genetic testing, but some mysteries remain

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Real Estate Transactions: May 3, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: May 3, 2024

Battery storage bylaw passes in Wendell

Battery storage bylaw passes in Wendell

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

The entrance is on one side of the nest and it might consist of little more than a slit through which the female can squeeze. A lifetime ago, when I worked for the U.S. Forest Service up in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, there was a graduate student from University of Massachusetts Amherst who was studying Ovenbirds.

His method of finding the nests was to rely on the help of a dog, but even with the keen senses of his canine companion, the nests were diabolically difficult to locate.

There is a healthy population of Ovenbirds that live in the woods to the south of my meadow and I have photographed them often, but I never remember seeing one so late in the season. The first weekend that I noticed this bird it seemed to be traveling along with a flock of Black-capped Chickadees. Always curious, but also cautious, this bird skulked through the underbrush and was never willing to pose for a picture. But I went to the same spot day after day and eventually the bird’s curiosity prompted it to pop out into the open for just a moment. I was ready and, “click,” we see this gorgeous creature perched on the branches of a dogwood with the rising sun reflected in its eye.

Bill Danielson has been a professional writer and nature photographer for 26 years. He has worked for the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the Nature Conservancy and the Massachusetts State Parks and he currently teaches high school biology and physics. For more in formation visit his website at www.speakingofnature.com, or go to Speaking of Nature on Facebook.

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock

Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces

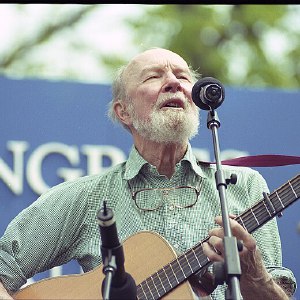

Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6

A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6