Native Insight: All signs point to Peskeomskut being a completely made up term

| Published: 02-09-2018 1:59 PM |

Leave it to Peter. Dr. Peter A. Thomas, that is — the esteemed Connecticut Valley historian, and perhaps the preeminent Historical Contact Period scholar of the Pioneer Valley. Pete is thorough, familiar with all the sources and wears a constant glow of warm intellectual curiosity and energy that never seems to wane.

Case in point, the word Peskeomskut, which has experienced a recent usage surge into the everyday Franklin County lexicon, thanks to the ongoing federal Battlefield Grant focused on the May 19, 1676 “Falls Fight.” This event is noted for turning the tide of King Philip’s War at the then majestic, natural falls between Riverside/Gill and Turners Falls. The problem is that we’ve settled on a word — spelled Peskeomskut or Peskeompskut, depending on what source you’re reading — that was introduced as a printed word in 1875 by the “Turners Falls Reporter,” a small community newspaper founded and edited by Gill bard Josiah D. Canning.

Now, with the federal study awaiting its second extension and third round of funding, Peskeomskut has been accepted as the ancient Native American name for the Connecticut River’s, and New England’s most spectacular, natural waterfall. Rev. Edward Hitchcock (1793-1864) said he could plainly hear the roar of the falls from the old Deerfield Academy, which he attended and became principal of (1815-18) before serving as Conway’s congregational minister (1821-25) and moving to Amherst College, where he served as a professor (1825-45) and president (1845-54). Hitchcock never once made any mention in print of the word Peskeomskut and, remember, he was the man who named the waterfall Turner’s Falls (after fallen “Falls Fight” Capt. William Turner) before the industrial Montague village came into existence and adopted the name during the second half of the 19th century.

Now, the Battlefield Grant is referring to the “Falls Fight” site as Peskeomskut, and local King Philip’s War authors Lisa Brooks (“Our Beloved Kin”) from Amherst College, and Christine DeLucia (“Memory Lands”) of Mount Holyoke College, are echoing acceptance of the word as the Native placename in their recently published books. Hmmmm?

Which brings us back to Thomas, who, as an archaeologist and historian, has a deep interest, not to mention hands-on experience, in both Connecticut Valley pre-history and history. That’s especially true at Riverside/Gill, where he led two archaeological excavations and supervised a third many years ago. Over the past few years, he’s been a constant public and private contributor to the ongoing Battlefield-Grant discussion and research. His book, “Maelstrom of Change,” about Springfield’s fur-trading economy, the Pynchon dynasty and Pioneer Valley settlement, is still a go-to source for Contact Period Pioneer Valley scholars. Plus, his archaeological fingers have probed deep in the dirt of such places as Riverside/Gill, Wills Hill in Montague, Fort Hill in Hinsdale, N.H., and many other deep-history sites of interest in our happy valley.

Thomas’ latest foray into Peskeomskut placename issue appeared in emails between him, Battlefield Grant leader Kevin McBride, a UConn archaeologist and various local historians throwing in their 2 cents’ worth when inspired. I was familiar with the topic, which we had discussed several times during casual conversation — the salient question always, “Why has this new round of research been so friendly to a word that has no known source, just appeared out of the blue in 1875 in, of all places, a small local newspaper that made absolutely no mention of a source?” And, “Now we have two scholars from elite colleges accepting it without question?” Curious, indeed. Enter Thomas, who dug into primary sources and Deerfield records in search of an answer.

What he found were many early references not named Peskeomskut, but instead locative mentions like “the upper falls of the Connecticut River,” “great falls,” “the falls at Deerfield,” “the great Fishery Place called Deerfield Falls,” “fishing falls above Deerfield Town,” and simply “the falls.” So, not a word close to Peskeomskut in the earliest records or narratives. Nothing. End of story. This void continued through the first quarter of the 19th century and beyond. Then, in 1836, Boston antiquarian author Samuel A. Drake introduced a new Native name of the falls in the process of criticizing Hitchcock for naming the waterfall after Capt. Turner. It went like this:

“… the Antiquary will always feel Misgivings when his Mind recurs to (Hitchcock’s name Turner’s Falls), because the original Indian Name (SQUAMSCOT) was rejected — rejected perhaps because it was generally unknown.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Of nearly 180 canoes in River Rat Race, Zaveral/MacDowell team claims victory

Of nearly 180 canoes in River Rat Race, Zaveral/MacDowell team claims victory

Wealth of historic Quabbin Reservoir photos available online

Wealth of historic Quabbin Reservoir photos available online

Greenfield seeks answers for $1M in state funds for Green River School

Greenfield seeks answers for $1M in state funds for Green River School

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Montague Police Logs: April 1 to April 8, 2024

Montague Police Logs: April 1 to April 8, 2024

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Too bad Drake didn’t give us a footnote or some other clue as to his source of the placename “Squamscott.” But, it is what it is: an unsourced name to forevermore vex diligent researchers. So here we sit, calling the site Peskeomskut because the short-lived Turners Falls Reporter called it that in 1875, without a hint of sourcing.

But, wait a minute.

There are clues as to what the word Squamscot meant in the different dialects of the Eastern Algonquian tongue our native people spoke. There is indeed a Squamscot River in southern New Hampshire that flows into Great Bay south of Portsmouth. According to one source: “The Squamscot, also spelled Swampscott and Swamscott, gets its name from the Squamscott Indians, who called it Msquam-s-kook (or Msquamskek) translated as “at the salmon place” or “big water place,” most likely in the Pennacook tongue. Both descriptions would fit the old waterfall between Turners Falls, and Gill as well. Plus, Thomas reached out to an Abenaki speaker for an equivalent word and the man came back with “Mskwamakok,” meaning place of salmon, the pronunciation again in the ballpark of Squamscott, which is in the neighborhood of Peskeomskut. Remember, phonetic English spellings and pronunciation of Native words can be, and most often are, unreliable butcher jobs. Perhaps relying on the Reporter reference is why historians George Sheldon and Josiah Temple call the falls “Pasquamscut” in their 1875 “History of Northfield.”

The go-to source for local Indian placenames is John C. Huden’s “Indian Place Names of New England” (1962), which identified Peskeompskut as a Nipmuck word meaning “at the split rocks” or “split-boulder place.” Though he has no entry for Sheldon and Temple’s Pasquamscut, he does include a similar Narragansett word Pessquamscot interpreted as “at the cleft rock” or “split-boulder place.” He also addresses Squamscut as an Abenaki word meaning “place at the end of the rocks” or “red rocks.” All of these descriptions fit the old natural waterfall at Riverside/Gill; and so does his Abenaki word M’squamscoook, meaning “at the abode of salmon.”

So, in closing — whether the folks now using it in an official, scholarly capacity want to admit it or not — the word Peskeomskut is most likely just one more eastern Algonquian word that’s been butchered by the English typewriter and tongue. I suppose we’ll just have to live with it until some long-lost reference comes to light in a dusty Queen Anne highboy’s hidden drawer.

Recorder sports editor Gary Sanderson is a senior-active member of the outdoor-writers associations of America and New England. Blog: www.tavernfare.com. Email: gsand53@outlook.com.

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock

Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces

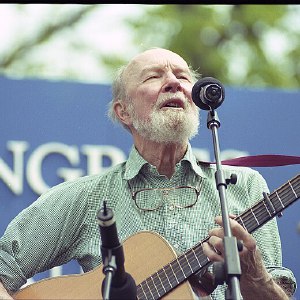

Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6

A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6