‘I credit her for our evolution’: A centennial celebration this week for Juanita Nelson, who chose subsistence farming over comfortable urban life

| Published: 08-14-2023 1:47 PM |

(Editor’s note: This is the second of two columns about Juanita Nelson’s centennial, which will be celebrated locally at events Aug. 17 through 20. Click here to read Part One.)

In midlife, Juanita Nelson — a college-educated woman with an elegant wardrobe and comfortable urban home — renounced most modern amenities and became a subsistence farmer. Why would someone whose enslaved ancestors were forced into grueling labor freely choose life without electricity, running water and other conveniences? What would inspire a brilliant woman to work the soil, build a small house from remnants of an old barn, and opt for an outhouse?

Juanita Morrow Nelson was a wonderfully complex character. This week, locals are invited to celebrate the longtime Deerfield resident and examine her philosophies and those of her life partner, Wally Nelson. The Juanita Nelson 100th Birthday Celebration and Gathering takes place Aug. 17 through 20 at the Woolman Hill Quaker Retreat Center on Keets Road in Deerfield, very close to the Nelsons’ former home.

As a Recorder columnist, I discover astounding creativity and innovation in Franklin County neighborhoods, villages and towns. I love each story — whether about seed-saving, native plants, weaving, herbs, kitchen remodeling, horses, making candles, or a multitude of other themes — yet no topic has a deeper place in my heart than this one.

Juanita Nelson and I weren’t directly related in a biological sense, but she was truly family to me. I lived with the Nelsons several times throughout my twenties; in 2002, they moved in with me for Wally’s last months. I held Juanita’s hand as Wally took his last breath and, two years later, Juanita laid eyes on my newborn son before I did, having accompanied me through labor. She was a no-nonsense yet doting grandmother during Gillis’s first decade, and helped me raise my son in joyful, unconventional ways.

The Nelsons relocated to Franklin County in 1974 after urban decades and a brief attempt at farming in New Mexico. They put down roots in Deerfield — thanks to the Woolman Hill Board of Directors — and became local fixtures. Their interests included organic farming, right livelihood, community economics, soapmaking, beekeeping, and many other elements related to living simply. Though it sounds deceptively easy, living simply is often difficult to accomplish in our society; Wally and Juanita devoted their lives to the pursuit.

The Nelsons knew many civil rights leaders, including Bayard Rustin, Pauli Murray and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. They became quite well known, themselves, as community organizers. Meanwhile, they achieved moderate success in fields including traveling sales, administrative work, radio drama and journalism. They could have continued comfortably, yet they chose to live off the grid, far below the official U.S. poverty level.

Roots of dissent are traceable to the Nelsons’ early lives.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Hotfire Bar and Grill to open Memorial Day weekend in Shelburne Falls

Hotfire Bar and Grill to open Memorial Day weekend in Shelburne Falls

Charlemont planners approve special permit for Hinata Mountainside Resort

Charlemont planners approve special permit for Hinata Mountainside Resort

$338K fraud drains town coffers in Orange

$338K fraud drains town coffers in Orange

Deerfield Planning Board OKs Hamshaw Lumber expansion

Deerfield Planning Board OKs Hamshaw Lumber expansion

My Turn: Quabbin region will never see any benefits from reservoir

My Turn: Quabbin region will never see any benefits from reservoir

September half-marathon to be Tree House Brewing Co.’s first 5,000-capacity event

September half-marathon to be Tree House Brewing Co.’s first 5,000-capacity event

“When I was 16, my mother asked me to accompany her to visit family in Georgia,” said Juanita in a 1987 interview. “I hesitated, because I’d never missed a single day of school — an odd point of pride.” Juanita decided it was worth spoiling her perfect record to visit relatives.

“We boarded a train in Cleveland and, at the Mason-Dixon Line, were instructed to move to the back of the train to a so-called colored car. I was incensed. I told my mother I was going to sit in every single train car in an attempt to claim my dignity.” Eula Morrow sighed heavily and told her daughter, “Nita, I wish you wouldn’t. But I won’t stop you.”

The teen went ahead with her plan, despite dirty looks and under-the-breath comments. Juanita walked the length of the train, sitting briefly in each “whites only” car. Finally, a Black porter urgently whispered that she should return to her mother. “Folks like us get hurt real bad or killed if we forget our place,” he said. Juanita looked him in the eye and said, “My place is with all people. So is yours.” The porter gazed at the floor and repeated that he didn’t want her to get hurt.

Juanita Morrow returned to her mother, whose shoulders relaxed in relief. “I hope you feel better,” she told her daughter, not unkindly. Juanita responded, “As a matter of fact, I do.”

A couple of years later, Juanita and a classmate at Howard University in Washington, D.C., entered a segregated eatery to challenge the racist policy held by restaurants, theaters, and other public places throughout the South. After being told they wouldn’t be served, the young women ordered hot chocolate, standing their ground until the waitress relented. “She finally slammed our cups down on the lunch counter, spilling about half the contents,” Juanita said in a 1991 interview. “She demanded that we each pay a quarter even though, on the menu, hot chocolate was a dime. We each put down a dime and turned to go, only to find ourselves in the company of two of D.C.’s finest … police officers who’d come to arrest us.” That was the first of Juanita’s many arrests.

When she met Wally Nelson in the mid-1940s, Juanita was a reporter for the Call & Post, a Cleveland-based African American weekly newspaper. While investigating how Blacks were treated while incarcerated in the Cuyahoga County Jail, Juanita met the love of her life. Wally was locked up for refusing to cooperate with the U.S. military; Juanita learned that he, too, had a history of resistance. Years later, she wrote a poem titled “Turn Loose the Line,” based on a true story from Wally’s youth.

As a nine-year-old, Wally plowed behind a mule on a sharecropping plot where his family cultivated cotton. One day, the mule became unruly and Wally was dragged through a field, weeping, until he realized that he could solve his dilemma. He freed himself by releasing the line, an experience that became a metaphor throughout his life.

While at Methodist youth camp, Wally took a pledge to follow the example of Christ by renouncing all forms of violence. Several years later, a minister visited Wally in jail, admonishing, “Young man, you’re a disgrace. What are you doing in here?” Wally replied, “I’m practicing what you taught me. What are you doing out there?”

Juanita credited her mother for modeling critical thinking and courageous action. “When she made up her mind about something, that was that.” Eula’s daughter, too, stood her ground, but also knew when to change her mind.

In the 1950s, the Nelsons formed an Ohio household with fellow peace activists Ernest and Marion Bromley. All went smoothly until neighbors discovered that the Nelsons were not, in fact, the hired help. “When people realized that we were living as equals, all hell broke loose,” said Juanita in a 1993 interview. “They held a mass meeting in the church across the street, intending to force us out. It didn’t work.”

In a 1988 interview, Ernest Bromley, a former minister and co-founder with Wally Nelson of the Journey of Reconciliation (one of the original Freedom Rides), said: “It cracks me up that the Nelsons became farmers. When we all lived together, Juanita wanted nothing to do with the garden. She wasn’t in the least bit interested in working the soil.”

A few years later, Juanita’s change of heart took even Wally by surprise. In a 1992 interview, he said, “I couldn’t believe what Juanita was saying. Us, farmers? I thought she’d get over it. But she believed it was our truest path to real freedom and, once again, she was right. Thanks to her, we’ve lived a decent life, learning to have less to do with things we don’t believe in. I credit her for our evolution.”

Juanita often said there’s only one way to stop war: “Stop participating in it, and stop so much consumption that requires war.”

There are many ways to learn about the Nelsons’ lives and wisdom, and those interested in attending the Juanita Nelson 100th Birthday Celebration and Gathering are encouraged to visit www.nelsonhomestead.org or to contact Betsy Corner, an event coordinator, by phone or text: 413-386-5559. Corner stresses that the organizing committee will not allow economics to prevent anyone from participating in the events. Which is just how Juanita Nelson would want it to be.

Eveline MacDougall is the author of “Fiery Hope,” a book containing several chapters about the Nelsons. A gardener, artist, musician and mom, MacDougall’s family farms in Québec, currently in their tenth generation on the same piece of land.

]]>

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock

Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces

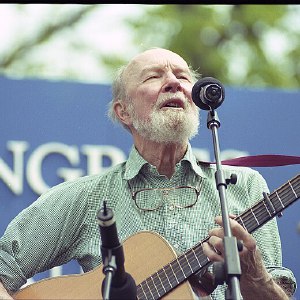

Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6

A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6