Take a day trip to a modernist paradise: The Frelinghuysen Morris Home & Studio in Lenox provides a splendid view of two groundbreaking artistic lives

| Published: 09-01-2023 3:05 PM |

A short drive from downtown Lenox, you travel past ornamental wrought iron gates and enter into the former Gilded Age estate of “Brookhurst.” You’re first greeted by a voluptuous two-and-a-half-ton reclining female figure sculpted by Gaston Lachaise.

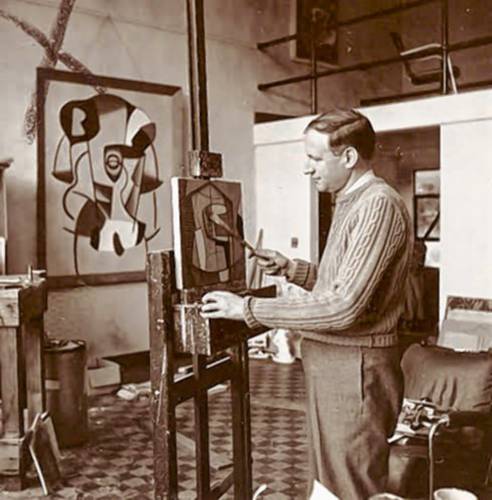

It’s an homage to his model who later became his wife. “La Montagne” (The Mountain) was commissioned by the author and painter George L. K. Morris (1905-1975) who spent his childhood summers here and later would build a studio and house on these grounds.

He may well be one of the most remarkable American artists you’ve never heard of — a man intent upon introducing European abstract art and “Cubism” to these shores. It was an epic battle.

“To be a modernist artist, and particularly to be an abstract artist, for an American in the 1930s, it was an uphill struggle,” the late art critic Hilton Kramer notes in a documentary shown at a nearby carriage house.

It’s a 10-minute walk through a dense hardwood forest, where George once played as a child, before the home and studio appear. You pass by two bridges, capped in white marble, while crossing March Brook, a meandering waterway that eventually flows into what is now known as the Stockbridge Bowl.

Native Americans called it “Mirror Lake” and proximate to it is a Native American and early settler burial ground. George was extremely influenced by Native American culture and its symbols are often found in his artwork. As an adult he financed an archeological restoration of the cemetery.

Brookhurst was his parent’s summer home. New Yorkers, they also kept a residence in Paris and frequently traveled throughout Europe.

He recalled in an interview that during a 1925 outing “it was really the first time I’d gotten to museums … from then on I decided that I wanted to become a painter.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

McGovern, Gobi visit development sites in Greenfield, Wendell

McGovern, Gobi visit development sites in Greenfield, Wendell

High schools: Seventh-inning rally helps Turners Falls softball edge Frontier 6-3 (PHOTOS)

High schools: Seventh-inning rally helps Turners Falls softball edge Frontier 6-3 (PHOTOS)

George was educated at Yale where he studied architecture and majored in English.

“Until I got to Yale, I’d never even heard of Cezanne,” he noted. “It’s incredible how little of Cezanne and Renoir were (commonly) known.”

Upon graduation he studied at New York’s Art Students League, and in 1929 he returned to Paris to be instructed by Fernand Leger in the 20th century’s most influential art movement, Cubism.

Hardly the starving artist, George hobnobbed with a Who’s Who of painters. This was when a Fernand Leger work could be had for $30 and a Piet Mondrian for $300. He secured a Pablo Picasso directly from the artist for doubtless an underwhelming sum.

Returning to Lenox, in 1931 George built a studio on a hillside below his parent’s estate and four years later he married Estelle “Suzy” Frelinghuysen (1911-1988). She grew up on a New Jersey estate named “Oakhurst” and, like her husband, was a talented pianist. She also had a trained operatic voice.

The author F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote, “The rich are very different from you and me.” The Morris wealth originated with a land grant that provided valuable real estate in what is now the Bronx.

Among Morris’ forebears were signatories to the Declaration of Independence and the first American-born Supreme Court Justice. His wife traced ancestry to 18th century Dutch Reformed Church preachers. Both shared past generations of people serving in public service and both were raised in opulent surroundings among a social class best described in the Edith Wharton novels.

The creation of the studio, with soft northern light captured by doubled skylights, was based upon a Parisian studio George had admired.

“He did a basic importation of a Le Corbusier design,” Kinney Frelinghuysen said shortly before a guided tour of the buildings. He’s Suzy’s nephew and the director of the 46-acre site.

Le Corbusier was one of the fathers of modern architecture and may be best known for his collaboration in designing New York’s United Nations building.

In creating the adjoining white stucco home, the couple relied upon a local architect. They shared in the planning of the interiors to create a very open, airy series of rooms in harmony with the environment. George also painted a large Native American-themed design on an outer wall.

“George added this mural which ties together this asymmetrical structure,” the director said. “It creates a sense of unity.”

No one has yet disputed the claim that the structure is the first modernist building created in New England.

As you enter the living room, there’s a step down to an intimate wet bar. The room, with a 1905 concert Knabe piano in the corner, has a leather floor and features a wall of windows framing a heritage apple tree and star magnolia fronting a lush garden and grounds.

George painted two frescos to either side of the fireplace, large enough in scale that they are referred to as “gentle giants.”

The house has several features, among them indirect lighting, an innovation at the time, as well as a spiral staircase and a dumb waiter for efficiently transporting objects between floors. A kitchen call box would alert staff that service was required in one of the rooms.

The studio displays a rich collection of small, individual paintings from Picasso to Georges Braque and Juan Gris.

Dominating the room are both Cubist and representational paintings by the couple. George encouraged Suzy to paint and she became well known in the arts years before she became a celebrated operatic singer.

“George is very devoted to abstraction,” Sean McCusker, an assistant to the director, said during a studio tour. “Suzy is freer in what she’s painting. His ultimate goal was pure abstraction and he felt that it was where art would lead.”

Suzy joined him in this mission to bring to American culture what he had seen among the avant-garde abstractionists in Europe. It was tough sledding, given that the vogue at the time were the representational paintings by such names as Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton.

Cubism, in simple terms, is a style of painting in which the conventional is abandoned and objects can seem to be shattered, with multiple perspectives, or as if seen through a kaleidoscope. Among the most famous is Marcel Duchamp’s 1912 “Nude Descending a Staircase” which one critic derided as looking like “an explosion in a shingle factory.”

George’s mother Helen forbade any of his abstract paintings to be hung in her Parisian home.

Due to their elite social standing, critics referred to the couple as “Park Avenue Cubists.” This is also the title of the comprehensive documentary regarding the artists, continually shown a short walk from the house.

Beginning in the late 1930s George edited and wrote art criticism for the “Partisan Review” and provided financing for the periodical. He was the founding member of American Abstract Artists that remains one of the few such Depression era organizations continuing to this day. The artist also served on the advisory committee for New York’s Museum of Modern Art and selected some of the paintings now in its permanent collection.

George was remembered as being a modest, somewhat shy and extremely witty person while his wife was much more headstrong and assertive. They made friends easily and upon the passing of his mother they legally adopted her nurse Sophie Von Enden. They were an inseparable trio until the early summer of 1975.

While driving in Stockbridge a truck slammed into their car, killing both George and Sophie. Suzy remained in a coma for days and was not stable enough to be informed of her losses until several weeks later.

Today the Brookhurst mansion is privately owned and the sales of the New York and Paris homes financed the creation of a foundation to manage the artistic properties.

In the 2005 documentary, the artist Will Barnet summed up George’s work quite succinctly. “His interest in architecture permeates his work … because Cubism has an awful lot to do with structure and structure has a lot to do with architecture. He was a poet that was an architect who became a painter.”

The Frelinghuysen Morris House & Studio season begins each year in late June. From Sept. 1 to Columbus Day, it’s open Saturday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is $20 for adults, and free for anyone under the age of 18.

For more information, visit: Frelinghuysen.org.

Proof that it’s never too late: Solo exhibit and free workshops honor the late Frederick Gao, a Belchertown resident who became a painter in his last five years

Proof that it’s never too late: Solo exhibit and free workshops honor the late Frederick Gao, a Belchertown resident who became a painter in his last five years Self-expression on display: ServiceNet members’ artworks on view at Greenfield Public Library through end of May

Self-expression on display: ServiceNet members’ artworks on view at Greenfield Public Library through end of May Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week