Direct from Paris, the Clark reveals 18th century romance

| Published: 01-06-2023 6:11 PM |

With admission now free until April, through March 12 at Williamstown’s Clark Art Institute you can view Parisian drawings and prints from the 1700s, ranging from colorful views of flowered landscapes to the mysterious and the fantastic. “Promenades on Paper” is the exhibit’s title as well as its companion catalogue (CAI; Yale University; 260 pgs. $50).

Many of the images have never previously been exhibited and several were once in the collection of royals. The show is composed of more than 80 art works and features several drawing devices commonly used in the 18th century. Its creation required the combined work of institute curators in tandem with Bibliotheque nationale de France (BNF) staff over the course of some 18 months. The Parisian institution is a repository of virtually all printed matter in the country, employs 2,500 people and has an annual budget of €254 million.

Clark Curator Sarah Grandin and BNF Deputy Head of Prints and Photographs Corinne Le Bitouze led a press reception through the galleries.

“They really rolled out the red carpet for us and made the work as easy as possible,” Grandin said, referring to the cooperation provided by the BNF through visits, Zoom conferences and emails.

There are some 15 million images of virtually anything in print from the country stored at the Paris site and due to its cavernous accumulation of paper works it’s one of the few places in Paris where smoking is forbidden.

“We don’t know exactly what we have,” Le Bitouze said at one point. “We have too many images. It’s impossible to know what we have.”

Available online is a brief, 1956 documentary about the BNF which filmmaker Alain Resnais titled “All The World’s Memory.” It depicts overwhelming canyons of papers and files. Following a recent 12 year renovation, however, the visual riches of the institution are now available digitally online at Gallica.bnf.fr.

Upon first entering the galleries, Grandin pointed out one of her favorite collections of images. At age seven Louis XV had already been King of France for two years. His pen and ink drawing of simple houses show a remarkable draftsmanship suitable for children’s books. In his memoirs he wrote that his tutor had “exhorted me to cultivate my natural royalty through the fine arts and literature.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

His reign would be the second longest of any French King and would span the “Age of Enlightenment.” It was the best of times in new discoveries in science and culture, a halcyon period.

“These drawings provide a fascinating testament to what Paris and France may have looked like in this period,” Grandin said.

Alongside the King’s work is a drawing created by a young Marie-Clotilde de France, the sister of Louis XVI. When she first explored the Royal Print Cabinet she was mesmerized by all the stunning scenes and portraits. Transfixed by these images, her governess had to tear her away from the premises. The young princess then donated this work to the collection.

“Her simple drawing at the age of 14 has made it all the way across the Atlantic now to be enjoyed by new audiences,” the curator said.

The increased availability of inexpensive paper democratized artwork and illustration became so popular that an art patron of that era decried that people were drawing too much and too often.

“Drawing became a very sociable practice,” Grandin said. “It’s something that one would do as part of polite society.”

Nevertheless there were set boundaries for women, who were often restricted to depictions of bird life and flowers.

“It was harder for women artists to make their trade in the depiction of historical subjects or portraits,” the curator said.

A brilliant botanical example is the work of Madeleine Francoise Besseporte, who in her mid-30s became the first female designated as the King’s official garden painter. She was also influential with the King’s mistress Madame de Pompadour, convincing him as to the importance of horticultural science. Besseporte also decorated porcelain and textiles and would whimsically add spiders and colorful moths to her flower studies.

There are also works by Emilie Bounieu who created virtually photographic depictions of biological and botanical studies. As one catalogue writer noted, one realistic drawing “seems to escape the two-dimensional confines of the page.”

At the time, women were barred from studying human form and the Royal Academy of Sculpture only allowed four women to enroll annually. They were not allowed to attend workshops.

For the privileged, a popular avocation was the promenade. Leisurely walks were taken through park pathways as a way of being seen and seeing. The exercise was so in vogue that many green spaces set aside special hours and days for such frivolity. You were also considered out of the loop if you didn’t carry a long cane.

Sophisticates were also wild about having their portrait created and the semi-automated “physiognotrace,” invented in 1783, was a remarkable aid to artists. It was several steps beyond the technique of tracing a person’s profile in the shadow of candlelight. The device allowed the artist to outline a sitter’s face with a stylus, while the movement was copied, with great detail, on paper nearby with another drawing instrument. There’s a model of this innovative apparatus in the Clark exhibit, alongside a finished product.

A camera obscura device, dating to the late 18th century, is also on view. With simple optics, an artist could trace a scene entirely as it was projected. When stowed, the antique, with flowered borders, simply collapsed into a cabinet no larger than a suitcase.

As to the fantastic, there are several architectural renderings of buildings that were never more than dreams. Before entering the galleries you’ll see an enormous blow-up of Etienne-Louis Boullee’s outlandish 1785 idea for a library featuring an enormous, semi-circular ceiling, myriad shelves to either side and enough space to land a small airplane. It’s an imagination run wild.

“You see how paper is really a site of possibility,” Grandin said. “You were unfettered by physical constraints.”

As outsized and incongruous is an unknown artist’s 1782 detailed rendering of a Parisian public square, entirely Romanesque with huge columns and completely contrary to the city’s style. The authorship of many of these grand depictions of theaters and public spaces are lost to history.

“Many of the artists and practitioners that we’ll encounter are less well-known and anonymous,” Grandin said, “but we still thought it was valuable to share these images.”

Among the more cartoonish illustrations are the depictions of the city’s “criers,” street merchants who sold wares ranging from brooms and hazelnuts to vinegar. The artist Claude-Louis Desrais adroitly captures their poses and professions. They were easily spoofed and there was even a board game based on their wanderings. A writer at the time noted “nowhere in the world do the criers have voices more bitter and more piercing.”

Drawing also served as documentation of what is now an entirely distant world. When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798 with 35,000 soldiers, he also brought 160 scholars and artists. Illustrators were overwhelmed with the drama and scale of the ancient monuments and many original drawings are here. Without documentation, valuable antiquities were hauled off to France and legend has it that French sharpshooters destroyed the nose of the Sphinx.

Napoleon is credited, however, with beginning the first serious studies of the ancient Egyptian culture. His glory was short-lived. The troops evacuated after three years and soon after, due to a British victory, England claimed the Egyptian treasures. This is why you can find the 2,000-year-old Rosetta Stone, the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, at the British Museum.

Continuing through February 12 and not to be missed is a small gallery exhibit in the Manton building. “On the Horizon” provides a chronological sampler of 19th century artists’ explorations of the atmosphere. During this time, there was a sea change in the artists’ perspective with discoveries in science and technology as to the properties of air as well as the new invention of manned balloons. Artists or photographers, now aloft, could provide the first bird’s eye views of landscapes. Increasingly, artists chose to make dramatic cloud renderings the dominant theme of their paintings and many also began to document the poisonous black smoke from industrial sites.

Admission to the institute is free through March 31. “Promenades on Paper” continues through March 12. The museum hours are Tuesday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Masks are optional.

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock

Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces

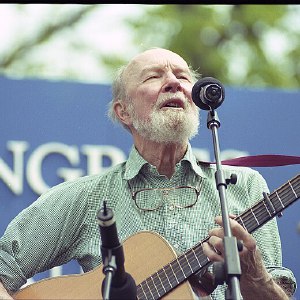

Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6

A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6