Visions from state’s past find a new home: Photographer gives antique glass negatives to UMass

| Published: 10-13-2023 1:53 PM |

Over three and a half years ago, documentary photographer Terri Cappucci received an unusual package: 4,000 glass-plate negatives of photos taken between about 1860 and 1920, courtesy of a collector who had no room for them and otherwise was going to throw them away.

Cappucci, of Turners Falls, wasn’t sure at first if she wanted to keep boxes of aged, bulky negatives in her studio, which she’d been trying to declutter.

But once she’d gotten a closer look at the quality of the black and white images and discovered many were from western Massachusetts, especially several towns in Franklin County, Cappucci knew she had something special on her hands.

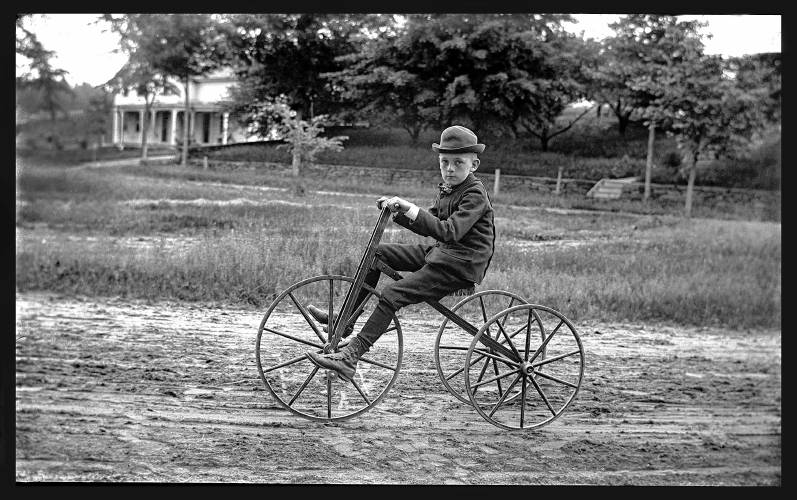

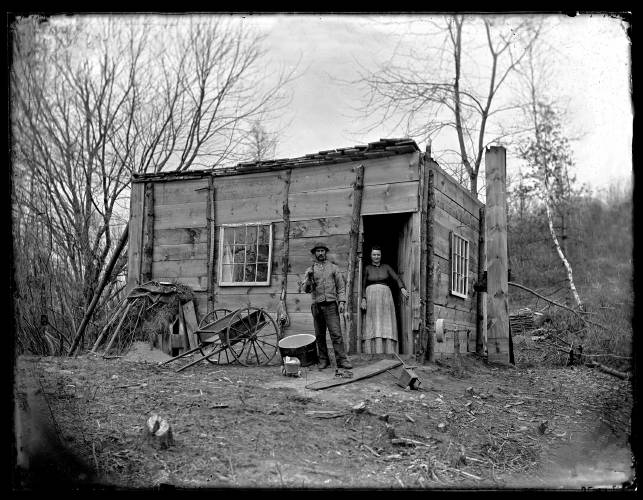

There were remarkable, sharp images: a boy riding an oversize tricycle with narrow steel wheels; a cluster of young women on a porch, identically dressed in white blouses, long dark skirts and straw boaters; a man and woman outside a rough wooden shack (in Northfield), the man with an ax slung over his shoulder and a few toys scattered on the ground.

In another, a well-dressed woman holds a lamb in her arms as she stands before a wire fence, a field and woods behind her; she wears a slightly bemused expression, and a large hat resembling a dark cushion seems to balance precariously on her head.

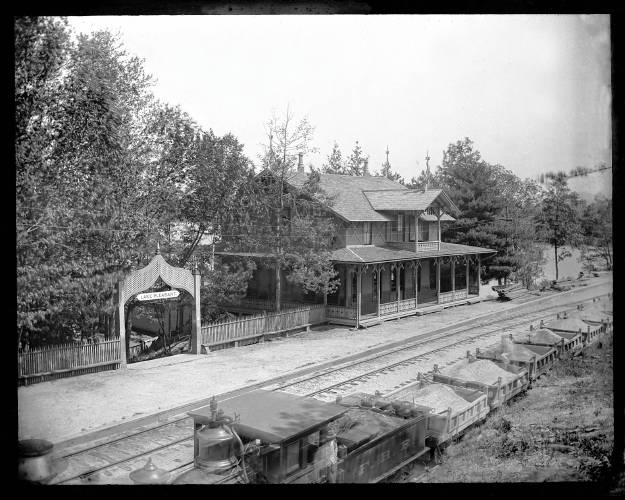

Though the locations of many of the photos were unknown, others could clearly be identified, such as a train station at Lake Pleasant in Montague, the approach to the Hoosac Tunnel, and the early “downtown” of Millers Falls.

“This was a fantastic piece of history,” said Cappucci, who’s also an educator and photo preservationist as well as a former photojournalist. In addition, for years she’s produced her own 19th-century-style photographs, through what’s known as the wet plate collodion process.

“These images were definitely worth preserving,” she said.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Serious barn fire averted due to quick response in Shelburne

Serious barn fire averted due to quick response in Shelburne

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11

Political newcomer defeats Shores Ness for Deerfield Selectboard seat

Political newcomer defeats Shores Ness for Deerfield Selectboard seat

Roundup: Pioneer baseball wins Suburban League West title following 2-0 win over Hopkins

Roundup: Pioneer baseball wins Suburban League West title following 2-0 win over Hopkins

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

Employee pay, real estate top Erving Town Meeting warrant

Employee pay, real estate top Erving Town Meeting warrant

Fast-forward to 2023, and the bulk of Cappucci’s collection, some of which she has already painstakingly cleaned, scanned, and digitized, is now at the UMass Amherst Libraries, specifically the Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center (SCUA).

The glass negatives can now be safely stored to prevent any damage from exposure to materials like acid-treated paper, Cappucci says, and SCUA staff say they plan to catalog and digitize the whole collection and make it part of their online archives, known as Credo.

It seems a fitting home for the vintage images, given Cappucci earned a bachelor’s degree in photojournalism and an MFA in photography at UMass.

“I was very happy they accepted my collection,” she said during a recent phone call. “This will be a great resource for so many people, not just for myself, and it’s a great visual history of our part of the state.”

Annie Sollinger, a visual archivist with UMass Special Collections, says in turn that the university is “really grateful” for Cappucci’s gift.

“Terri’s taken on a lot of the work with this already, and she’s done an amazing job,” said Sollinger. “She’s given us some really valuable guidance on how we can take the next steps on the project.”

“This is a wonderful addition to our archives,” she added, noting that though SCUA has about 100 photo collections in its archives, few offer the kind of historic regional images that Cappucci uncovered.

Cappucci said her initial reservations about examining the glass negatives gave way after COVID-19 arrived. Hunkered down at home, she said, “This was an interesting project to work on.”

She loved the sense of discovery the work provided, though few details about many of the negatives — date, place, the name of the photographer — were included. Cappucci created an online site, Somebody Photographed This, and posted some of the images there and on her Facebook page to seek public input on possible origins of the work.

She was also able to raise about $7,000 through a GoFundMe campaign to help pay for some of her work and for expensive archival materials, including acid-free envelopes and proper storage boxes for the negatives.

Her knowledge of early photographic techniques helped her date some of the plates, she says, and she was able to identify certain landscapes straightaway, such as 19th-century views of Bernardston, where she grew up.

Some of the images were too damaged to be saved, but most were still in good shape and remarkably clear.

“I can tell that a lot of these were taken by someone who really knew what they were doing,” Cappucci said. “They took the time to compose the images, they had good lighting, and they used proper exposures.”

The glass plate negatives themselves, which are mostly 5-by-7 inches or 6.5-by-8.5 inches, help enhance that sharpness: “The bigger the plate, the better the quality,” she noted.

Aside from these technical aspects, Cappucci says she was entranced by images of life from up to 160 years ago, wondering about the people in them and what they might have been thinking as they posed for pictures, which required very long exposures.

“There’s a reason you don’t see people smiling in these photos,” she said with a laugh, noting that it’s “a real challenge” to hold a smile for minutes at a time.

She was particularly taken by an image of an elderly woman, seated on a wooden chair somewhere outside, with a man standing at her side, holding something above her. There’s no way to know what it is, as the top of the photo ends at the man’s neckline and his right hand.

“Was he holding an umbrella? Was he a family member or someone who worked for the [women’s] family?” said Cappucci. “Or was he working with the photographer, holding up some additional lighting? It’s quite the mystery.”

Sollinger, the UMass archivist, says the university may be able to help solve some of those mysteries. Once SCUA begins cataloging the images and posting them online, “We’ll encourage people to contact us if they have information they can add for specific photos,” she said.

Cappucci had another compelling reason to move the glass negatives from her studio. From the mid 1990s to 2014, she visited South Africa annually for a photo project that examined life there in the post-apartheid era. Then a drain pipe accident flooded her basement in 2015, destroying the work.

The images in what’s now being called the Terri Cappucci Glass Plate Negative Collection will have a safer home at UMass, she said.

“I had to do a lot of research and training to fully understand what would give this collection the best chance for a long life,” she noted in an email. SCUA, she says, is the kind of archive that would “treasure them and be sure they were made available for research.”

“I was truly honored that they saw the value in them and accepted,” Cappucci said.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.

On Mother’s Day, we’ll always have Paris: A crêpe recipe in honor of my French-speaking mother

On Mother’s Day, we’ll always have Paris: A crêpe recipe in honor of my French-speaking mother Providing opportunity for people to grow: The United Arc of Franklin County’s annual Gardening with Steve event a highlight of spring

Providing opportunity for people to grow: The United Arc of Franklin County’s annual Gardening with Steve event a highlight of spring Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song

Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song The house that therapy built: Multimedia artist Lisa Winter to display “My House” at the Wendell Meetinghouse this Sunday

The house that therapy built: Multimedia artist Lisa Winter to display “My House” at the Wendell Meetinghouse this Sunday