Walking the earth, with a bit of swagger: Documentary film profiles the groundbreaking all-female rock band Fanny

| Published: 06-16-2023 3:13 PM |

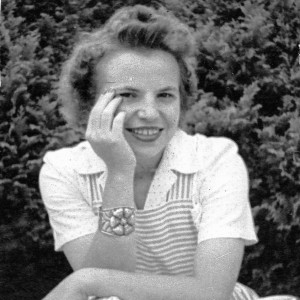

June Millington is a familiar name in the Valley music scene, a veteran guitarist and educator who since the early 2000s has overseen numerous programs at The Institute for the Musical Arts (IMA), the Goshen center dedicated to supporting women and girls in music and music-related businesses.

And people familiar with Millington’s story know she was also once part of Fanny, a spirited rock and roll band that made history in the early 1970s when it became the first all-female rock group to release an album on a major record label, earning plenty of critical praise before breaking up in 1975.

But how well is Fanny’s story known today? Canadian filmmaker Bobbi Jo Hart had never heard of the band when she came across a biography of Millington on the Taylor Guitars website several years ago, as she searched for an acoustic guitar for her daughter.

“I was completely thrilled and completely pissed,” Hart said in a recent phone while taking a train between Montreal and Toronto. “How is it I had never heard of this group? I’d grown up loving rock and roll, my parents had a huge collection of records, but (Fanny) was a complete mystery.”

“I wanted to tell their story and give them their due,” said Hart.

She’s done just that with “Fanny: The Right to Rock,” her lively documentary now streaming on PBS. Combining interviews with most of the former band members along with many period photographs and TV and film clips, the documentary makes one thing very clear: These women could rock.

David Bowie was a notable fan. In late 1999, he told Rolling Stone that Fanny was “extraordinary: They wrote everything, they played like (expletive), they were just colossal and wonderful, and nobody’s ever mentioned them.”

All told, the band, which included June’s sister Jean on bass, released five albums on Warner/Reprise Records, opened for groups like Humble Pie, Chicago, and Jethro Tull, and built a particularly strong following in Great Britain. They also backed up Barbara Streisand in the studio on two of her albums.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Political newcomer defeats Shores Ness for Deerfield Selectboard seat

Political newcomer defeats Shores Ness for Deerfield Selectboard seat

South County Senior Center opts not to renew church lease after rift over LGBTQ program

South County Senior Center opts not to renew church lease after rift over LGBTQ program

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

Moratoriums on large-scale solar, battery storage passed in Northfield

Moratoriums on large-scale solar, battery storage passed in Northfield

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11

Aside from their musicianship, Fanny also served as an inspiration for any number of female musicians and bands. Hart interviews a number of them — Bonnie Raitt, Cherie Currie of the Runaways, Kathy Valentine of the Go-Go’s – who testify to the band’s stature as roll models for succeeding generations of female rockers.

“Fanny is iconic – truly before their time,” says Currie, while Raitt remembers them as “the first all-women rock band that could really play and get some credibility within the musician community.”

It’s not just the women who say this. John Sebastian from The Lovin’ Spoonful, Earl Slick, David Bowie’s lead guitarist, and Joe Elliot from 1980s hard rockers Def Leppard all sing the band’s praises, too. (It should be noted that Slick and Jean Millington were once married and had two children together, and Bowie also dated Millington for a time in the mid 1970s.)

Hart presents much of the band’s background in conjunction with visits she made to the IMA in Goshen, where four of Fanny’s original members – the Millington sisters, drummer/singer Brie Darling, and drummer Alice de Buhr – reunited in 2017 to record a new album, “Fanny Walked the Earth.”

The contemporary scenes have a real warmth as the band members renew old ties and, in one scene, cruise down a dirt road in a convertible, stealing an image from “Thelma and Louise.”

“They’re like my sisters,” says Darling. “I’ve known them since I was 16.”

They also joke about how despite their white and graying hair – they’re all in their late 60s at this point – they’ve held up pretty well compared to some other older rockers: “The Rolling Stones look pretty darn ancient,” says one band member.

Hart does an excellent job unraveling the complicated timeline of Fanny’s story and weaving that into her interviews. The story begins in the Philippines in the late 1940s, where June and Jean were born to a Filipina mother and white American father. The family moved to northern California in the early 1960s, where the Millington sisters had their first brush with racism.

Jean Millington recalls having a white boyfriend in high school whose father offered to buy his son a car if he’d dump Jean and date a white girl.

“He did,” says Jean. “He dropped me for a Mustang.”

Yet their early love of music gave the sisters a means to combat that kind of prejudice; they were inspired by The Beatles and other pop groups of the era to form a band that grew to include keyboard player Nickey Barclay, Darling, and de Buhr. (The record company later insisted Darling be dropped to keep the band at four members, though she would eventually rejoin the group.)

They were signed to Reprise by Richard Perry, who’s also interviewed in the documentary – “June was a ball of fire,” he recalls – after Perry saw them play an open mic at a popular club, the Troubadour, in West Hollywood in 1969.

By the following year, they’d released their first album; an iconic photo in the film shows a huge billboard on Sunset Boulevard in 1970 promoting the band for an upcoming gig at another legendary LA club, the Whisky A Go Go.

“They were breaking all kinds of barriers, and they were doing it on their own,” said Hart. “And they were all so young!”

The band members also moved into a Hollywood home they named Fanny Hill, which became their rehearsal spot as well as a popular drop-in site for all manner of musicians, from Raitt to Mick Jagger to Joe Cocker to Lowell George.

This being the early 1970s, it was “pretty much sex, drugs, and rock and roll” at the house, Darling recalls. Raitt has one of the film’s funniest lines as she remembers her bass player, Daniel Friedberg, better known as Freebo, being “frustrated” at Fanny Hill because “there were a lot of gorgeous naked women walking around, all of whom were gay.”

That’s not quite accurate: June Millington and de Buhr were lesbians, though they couldn’t be out publicly at the time. But the band also had to deal with the general sexism and misogyny of that era, including in the rock world. As the film relates, Lester Bangs, a prominent U.S. rock critic of the 1970s, once wrote “Women’s rock groups suck.”

June Millington quit Fanny in 1973 after the record company pushed the band members to dress more sexy for gigs. “I always felt trapped in that one-dimensional way they presented us to the world,” she says.

“The sad thing is that a lot of those attitudes haven’t changed,” said Hart. “Women in rock are still sexualized, they still face misogyny — it’s just so disrespectful.”

Her film also suggests Fanny never got enough support from Reprise to keep going – or maybe not having a hit single was the problem. Their highest charting song, “Butter Boy,” reached #29 in 1975, but the band, after more lineup changes, had split up for good by that point.

Barclay, the keyboard player, does not appear in the film, though Hart says she tried hard to reach her. The documentary alludes to past tensions within the band with Barclay, Hart notes, but she says she didn’t want to go into details without Barclay’s voice as part of that.

On the other hand, Hart says she got a huge assist from photographer Linda Wolf, an old friend of the band members, who gave her 80 vintage photos of Fanny from the early 1970s.

“She trusted me with her original contact sheets, that I would mail them back to her after I’d scanned them,” said Hart. “I’m so grateful. I don’t know that I could have made the film without her help.”

There’s one more somber note to the documentary. Following scenes showing Currie, Valentine and other women rockers adding backup vocals to the new album, you learn that Jean Millington suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of her body – just before the reunited band was about to do their first tour in years.

Yet “The Right to Rock” stands as a fine piece of music history and a reminder, Hart says, of the group’s impact on the female rock groups that followed them. “And girls and young female musicians can still see them as mentors today,” she said. “That’s their great legacy.”

As June Millington puts it, “We didn’t try to convince anyone girls could play, we just (expletive) did it.”

“Fanny: The Right to Rock” streams on PBS through June 18, and it’s also available for streaming on several other online sites such as Apple TV and Amazon Prime Video. The DVD can be purchased on many online sites.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.

Sounds Local: Joni Mitchell tribute comes to Turners Falls: Big Yellow Taxi to perform ‘Court and Spark’ in its entirety, May 18 at the Shea

Sounds Local: Joni Mitchell tribute comes to Turners Falls: Big Yellow Taxi to perform ‘Court and Spark’ in its entirety, May 18 at the Shea On Mother’s Day, we’ll always have Paris: A crêpe recipe in honor of my French-speaking mother

On Mother’s Day, we’ll always have Paris: A crêpe recipe in honor of my French-speaking mother Providing opportunity for people to grow: The United Arc of Franklin County’s annual Gardening with Steve event a highlight of spring

Providing opportunity for people to grow: The United Arc of Franklin County’s annual Gardening with Steve event a highlight of spring Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song

Speaking of Nature: Capturing my Bermuda nemesis: The Great Kiskadee nearly evaded me, until I followed its song