The different sides of James Baldwin: Mead Museum exhibit showcases writer’s artistic connections

| Published: 03-10-2023 7:59 PM |

It’s mostly a lesser-known footnote to his career: From 1983 to 1986, James Baldwin was based at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he was part of the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies and taught students from across the Five Colleges.

It seems fitting, then, that an exhibit that examines the famous writer’s connections to the arts is enjoying just its second staging, this time at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College.

“God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin,” which runs through July 9, features a wealth of photographs, drawings, paintings, archival materials and more that together present a broad look at the writer’s life and work.

More specifically, the exhibit, created by the writer and theater critic Hilton Als, is designed to examine Baldwin’s relationship to, and interest in, the visual arts.

As Als writes in his exhibition text, Baldwin, born in New York in 1924, was a “latter-day flaneur [a stroller or observer of life] cruising the streets of Paris, capital of the nineteenth century, and his native Manhattan, capital of the twentieth century, seeking out those artists and scenes and exchanges that helped make him the artist he always longed to be.”

Lisa Crossman, the Mead’s curator of Arts of the Americas, says the exhibit serves as a great means to welcome back a wider audience to the museum: The Mead just reopened Jan. 31 to the public after being closed for nearly three years because of the pandemic and then some construction.

Crossman also notes that the show, which features artworks created during Baldwin’s lifetime and afterward, including varied portraits of the writer, makes the case that Baldwin’s work and legacy continue to reverberate through the artistic community.

“There were a lot of dimensions to his life,” Crossman said during a recent tour of the exhibit. “There was his writing and the breadth of it, there was his involvement in the civil rights movement, and there was the way he examined societal issues through his writing.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

As a Black man growing up in segregated America, and as a gay man living well before the LGBTQ community gained wider acceptance, Baldwin faced particular hurdles, especially racism, “yet [racism] did not erode his aestheticism,” Als writes.

In fact, Als notes, Baldwin sometimes made fun of assumptions about him. When a TV interviewer once asked him if being “black, impoverished, and homosexual” gave him pause, writes Als, “Baldwin smiled and said, ‘No, I thought I had hit the jackpot. It was so outrageous, you had to find a way to use it.’ ”

As the exhibit outlines, one of Baldwin’s key artistic connections was with Richard Avedon, the noted fashion and portrait photographer, who was a high school classmate in New York; the two worked on the school’s literary magazine, “The Magpie,” in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

“God Made My Face” includes two iconic black and white photos of Baldwin that Avedon took in 1945, when Baldwin was 20 or 21, as well as some contact sheets from a 1962 photo shoot Avedon did of Baldwin and his mother, Emma Berdis Baldwin.

Baldwin and Avedon would also collaborate on a seminal 1964 book, “Nothing Personal,” a book of photos by Avedon and essays by Baldwin that explored American identity.

A contemporary artist, the South African-born painter Marlene Dumas, touches on this connection with a set of five ink and graphite portraits from a 2014-2018 series she calls “Great Men.” The set includes images of Baldwin, Avedon, Marlon Brando, Langston Hughes, and Beauford Delaney.

That last portrait points to another important artistic touchstone for Baldwin. Delaney made a name for himself as a painter during the Harlem Renaissance, and Baldwin sat for a portrait by him when the future writer was still in his teens; he came to greatly admire Delaney’s work.

Like Baldwin, Delaney was gay, and like Baldwin and some other Black American artists of that era, he lived in Paris in the 1950s, finding a greater sense of freedom there than in the U.S.

The Mead exhibit includes an abstract gouache painting by Delaney from 1958, as well as a photo of Baldwin and Delaney sharing a table in a Paris restaurant circa 1965.

“I think that’s one of the appealing things about the exhibit,” Crossman said. “Hilton has really pulled together a lot of different pieces to show the different connections [Baldwin] had in his life.”

Als, who wears a number of hats — educator, essayist, theater critic for The New Yorker — has won a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Critics Circle Award, both for criticism. He originally organized a somewhat different version of “God Made My Face” for a New York City gallery in 2019.

He gave a tour of the Mead exhibit at its opening reception Feb. 24, when he was also in Amherst to speak at LitFest, the college’s annual literary festival.

The exhibit offers a number of reference points from the Pioneer Valley, including from Baldwin’s time here as a teacher. For instance, there’s a reproduction of a 1984 Gazette interview with Baldwin and some of his Five College students, and an etching of Baldwin by the Valley sculptor Leonard Baskin.

Then there’s a playbill from “Topdog/Underdog,” a 2001 off-Broadway play by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and screenwriter Suzan-Lori Parks, a 1985 Mount Holyoke College graduate who took at least one course with Baldwin and — according to the 1984 Gazette article — thought he was an excellent teacher.

“His reputation came into the room before him but he surpassed it,” Parks said. (Her opinion was not shared by some of the other students quoted in the article.)

Aside from his novels and essays, Baldwin also wrote poetry and plays. One of the exhibit’s most intriguing artworks, by the Nigerian-American artist Njideka Ankunyili Crosby, is connected to a passage from his 1964 play “Blues for Mister Charlie,” a work that was partly based on the infamous 1955 murder of Emmett Till, a black teenager from Chicago killed by white men in Mississippi.

Crosby’s enormous (just under 7 by 7 feet) mixed-media and collage piece, “Nyado: The Thing Around Her Neck,” speaks to the artist’s own challenge in bridging the differences between Nigeria and the U.S.

Also on display: a series of videos by Kara Walker, showing the trademark silhouette-based work of the artist, who’s generally considered one of the most prominent Black artists in the U.S. today.

Yet one of the exhibit’s most appealing features is a collection of photos and digital slide projections of Baldwin taken in more casual circumstances: visiting Turkey, chatting with a man outside a New York theater, and dancing with a CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) worker in New Orleans in 1963.

And Als adds something personal to his exhibit, an account of visiting the site of a small stone house in southern France where Baldwin died in 1987.

In notes that accompany a display of three large stones, Als writes that he was given a tour in 2017 of the mostly demolished site by a young woman “who asked if, by way of remembrance, I would like to have some stones from Baldwin’s terrace. These are those stones.”

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock

Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces

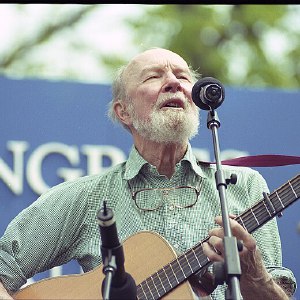

Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6

A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6