State’s rental assistance leaving families in limbo

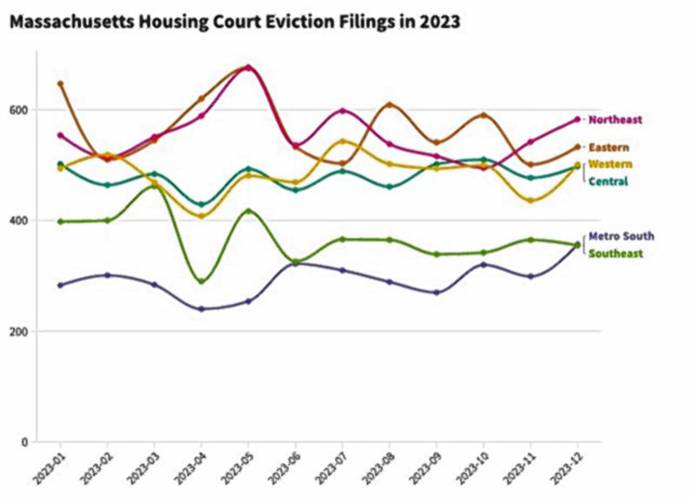

A graph of housing court eviction filings by region in Massachusetts in 2023. GRAPHIC BY XINYI YANG USING DATA FROM MASSLANDLORDS.NET

|

Published: 03-19-2024 1:01 PM

Modified: 03-20-2024 7:03 PM |

Anna Smith has applied three times to a state program that provides rental assistance for families — before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic — with the intention of “saving her two kids and her life.” What she didn’t anticipate was such a bleak outcome.

January marked the third time that the 28-year-old Springfield resident’s application for the state’s Residential Assistance for Families in Transition program (RAFT) has been rejected. The program, which falls under the Massachusetts Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities, turned down her request for assistance in relocating to a new home. The agency says it is now helping both homeowners and renters — it previously assisted just renters — which means its pool of money doesn’t go as far.

In a nutshell, the RAFT program provides $7,000 per 12-month period to help tenants with back rent or with “startup costs” for a new unit. Examples of “startup costs” are first and last month’s rent and a security deposit.

To apply for RAFT, both a tenant and a landlord have to complete corresponding applications. If the application is approved, payment will be submitted directly to the landlords after the applications are reviewed by a regional office.

A renter, according to the state agency, must prove a “legitimate need to move,” an inability to pay rent or a threatened eviction by their current landlord. Smith fell short of their standards.

“It’s not like it was during COVID,” said Smith, who lost her job in a restaurant in 2020 and relocated to a new, but “horrible” home after reapplying and using her RAFT voucher. “It was also really helpful when I first applied for it.”

The Healey administration’s fiscal year 2025 state budget proposes to fund the RAFT program at $197.4 million, a $7.4 million increase over the current fiscal year.

Experts in the field worry that the funding increase is not enough to offset changes that went into effect last July that are having an impact on program participants. Some of those changes include extending the program to homeowners and reducing the maximum amount of benefits a household can receive over a 12-month period from $10,000 to $7,000. It should be noted, however, that the max amount was $4,000 a year prior to the pandemic.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

1989 homicide victim found in Warwick ID’d through genetic testing, but some mysteries remain

1989 homicide victim found in Warwick ID’d through genetic testing, but some mysteries remain

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

Fogbuster Coffee Works, formerly Pierce Brothers, celebrating 30 years in business

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Greenfield homicide victim to be memorialized in Pittsfield

Real Estate Transactions: May 3, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: May 3, 2024

Battery storage bylaw passes in Wendell

Battery storage bylaw passes in Wendell

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

In addition, successful applicants are no longer eligible to receive reimbursement for any expected rental costs other than current debts or arrears.

“Generous benefits had to adjust to help more, because people in demand are increasing,” said Keith Fairey, president and CEO of Way Finders, a nonprofit affordable housing development company serving western Massachusetts.

According to state data, the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities served approximately 57,000 households through RAFT between the beginning of 2020 and the end of March 2023, with Springfield ranking first in need. The number of applications has remained steady at about 3,500 each week since the pandemic ended.

Smith said the application process has since been streamlined.

“You may receive your paycheck in a week — it’s like a life-saving tool — with fewer questions answered, zero paperwork required and shorter approval processing times,” she said. “It is crucial for applicants to use this time. Landlords typically are unwilling to wait too long after they have discovered a property, and since the RAFT application needs their signature and participation, many of them initially reject lessees who are funded by RAFT.

“It was so hard to even find a landlord who would sign,” Smith said, “and often they required you to pay three times the rent to hold the house.”

Massachusetts ranks as the third least affordable state in the United States for housing, according to the Out of Reach 2020 report, behind only California and Hawaii. For 2020, an employee would need to make $35.52 per hour to afford a two-bedroom rental property at the fair market rent of $1,847 without having to spend more than 30% of their salary on housing.

However, as of May 2022, the median wage for all occupations was $28.10 an hour, which means that half of the people who earned under this amount could not reach even an average income in Massachusetts.

Another challenge for renters who make low pay is a consistent increase in fair market rent. The current average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the greater Springfield area is $1,223 for two bedrooms or $1,497 for three bedrooms.

Advocates claim that even if the monthly subsidy went back to $10,000, it would still be insufficient for larger families or households in locations with more expensive real estate.

“Seven thousand dollars is not enough,” said Kelly Turley, the Springfield area associate director of the Massachusetts Coalition for the Homeless, an advocacy team providing long-term solutions to poverty and homelessness. She described Massachusetts as “consistently unaffordable.”

An EOHLC spokesperson said the benefit was $4,000 prior to the pandemic, matching the amount that the average RAFT applicant asks for.

“The administration balances providing an effective benefit with being able to help as many Massachusetts families as possible,” the spokesperson said.

According to Turley, the majority of RAFT applicants requested financing because they received notices to quit or eviction notices from their landlords, despite the fact that others were experiencing financial hardship due to layoffs. Massachusetts Housing Court received 38,863 eviction filings in the last year, which is 70.5% more than in 2021.

“Can you imagine hundreds of people facing eviction every day when you sit in the Housing Court?” said Smith.

Massachusetts saw legislative efforts last year to make some eviction protections permanent, particularly through the re-enactment of and calls for extension of Chapter 257, a law originally intended to halt eviction cases for tenants who had applications for rental assistance pending. The goal was to protect renters and increase landlords’ rental aid payouts.

What happens, then, if the defendants’ outstanding balance is more than the current benefit cap can sponsor and they do not have access to any other resources to cover the difference, Turley asked. Even though the RAFT application is still pending, the judge would likely proceed with the eviction.

“So this is our concern right now: We do not believe the homeless prevention efforts could play a part by capping it at that amount,” Turley said.

Increasing investment should only be a solution to address the issues, she said.

More than 40 Massachusetts legislators, led by Rep. Marjorie Decker, D-Cambridge, sponsored the coalition’s proposal for Providing Upstream Homelessness Prevention Assistance to Families, Youth and Adults, a measure currently before the Legislature’s Housing Committee after lawmakers agreed to extend the reporting deadline.

The bill would, according to Turley, forbid the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities from requiring tenants to obtain a notice to quit from their landlords and a utility company shut-off notice to be granted back rent assistance. It also would provide upstream access to benefits, raise the monthly RAFT benefit cap beyond $7,000 per household and allow it to incorporate more elements of the previously federal-funded Emergency Rental Assistance Program.

Finally, the bill would maximize resources from RAFT, HomeBASE and other rental assistance programs.

Senate Ways and Means Chair Michael Rodrigues, D-Westport, speaking during the coalition’s recent State House lobbying day, said “the Senate will have a broad, comprehensive conversation on all the issues surrounding the emergency assistance program and providing services to the migrant families here in Massachusetts.”

The coalition plans to push for permanent implementation of RAFT and other homelessness prevention programs in the coming years to increase access for vulnerable residents. The coalition also supported legislation that would fortify rental assistance programs and create a bill of rights for those who are homeless.

“We will continue to advocate to raise that cap, to go back to a minimum of $10,000 and to push for more flexibility to help people use RAFT more effectively,” Turley said.

Xinyi Yang writes for the Recorder from the Boston University Statehouse Program.

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11

Bridge of Flowers in Shelburne Falls to open on plant sale day, May 11 Community Legal Aid expands Disability Benefits Project to Franklin County

Community Legal Aid expands Disability Benefits Project to Franklin County Wear Orange organizers prepare display to remember gun violence victims

Wear Orange organizers prepare display to remember gun violence victims Deerfield candidates, Whately incumbent discuss issues with voters at South County Senior Center

Deerfield candidates, Whately incumbent discuss issues with voters at South County Senior Center