Ratepayers fed up with high energy costs

AP PHOTO/JEFF ROBERTSON AP PHOTO/JEFF ROBERTSON

| Published: 02-27-2024 10:37 AM |

BOSTON — From the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in Lynn to the state’s western border in Richmond, people in Massachusetts are letting the state know how they feel about wallet-busting energy bills.

“I struggle to pay my bills, my electric runs $250 a month and in the winter I am paying $500 a month to heat our home. I have many other bills aside from these bills including car payments, insurance, food cost and everyday necessities. I don’t qualify for assistance of any kind,” Dacia Clark, a single Pittsfield mother of four children who also cares for her disabled mother, wrote to state officials last month. “I know many other residents of Massachusetts have the same struggle as me. My time is limited with my family because I work so much in order to keep up on the bills, I pray there will one day be something done to help take a little weight off all the responsibilities we carry as responsible parents trying to juggle it all.”

Travis Roger from Richmond shared a copy of a recent electric bill showing that it cost him “over $500 a month to keep our electric on.”

“We are a family trying to raise three young children, living paycheck to paycheck. We simply CANNOT afford to pay over $500 a month to keep the electric on,” Roger wrote. “My weekly paycheck isn’t much more than my monthly Eversource bill and my electric is only one bill of the many bills that I need to pay each month.

More than half our of Eversouce bill is delivery fees!! We are left helpless,” he continued. “Families are struggling to make ends meet, struggling to keep the lights on, and struggling to feed their families. Something needs to be done.”

Clark, Roger and more than a dozen others submitted their comments as part of an official “inquiry” the Department of Public Utilities launched in early January scrutinizing the high costs of energy bills and potential improvements to energy affordability programs that could reduce that burden on residential ratepayers.

After a public input period that runs through Friday, DPU will hold meetings to explain the changes under consideration and then issue a written order detailing any changes it might mandate to the energy affordability programs that utility companies are required to offer.

“Possible measures include offering varying levels of discounts depending upon income or placing a cap on the percentage of income spent on bills from energy utilities,” the department said in its announcement.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

Retired police officer, veteran opens firearms training academy in Millers Falls

Valley lawmakers seek shorter license for FirstLight hydropower projects

Valley lawmakers seek shorter license for FirstLight hydropower projects

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

More than 130 arrested at pro-Palestinian protest at UMass

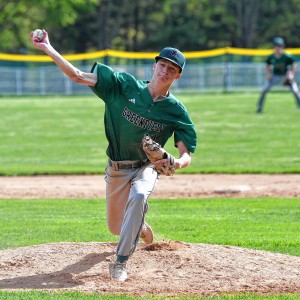

Baseball: Caleb Thomas pitches Greenfield to first win over Frontier since 2019 (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Caleb Thomas pitches Greenfield to first win over Frontier since 2019 (PHOTOS)

Real Estate Transactions: May 10, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: May 10, 2024

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

As I See It: Between Israel and Palestine: Which side should we be on, and why?

Blanca Hurrutia and a handful of other Lynn residents shared similar comments with DPU, writing in Spanish that no one should have to reduce their food consumption to keep their lights on “pero eso está sucediendo ahora,” which means “but that’s happening now.” Hurrutia and others also suggested to DPU that the state should cap utility bills at a maximum amount based on the customer’s income.

Massachusetts has some of the highest energy costs in the country. Many households that earn 80 percent or below the state median income level “endure financial hardships in relation to paying utility bills,” DPU said, and lower-income households pay as much as 3.5 times more of their income on energy than other households.

As part of its clean energy pursuit, the state is pushing businesses and residents to use electric-based energy and vehicles, an effort that is causing all parties to further scrutinize electricity costs.

A letter submitted by the chair of the Longmeadow Energy and Sustainability Committee said that “the electricity bills have increased substantially” for residents who have already begun the electrification transition.

“At the same time, because contractors continue to recommend that homeowners continue to keep, and use in cold weather, gas-burning furnaces, these homeowners incur gas charges that have yet to decrease in significantly meaningful ways,” Andrea Chasen wrote in a letter that included detailed information on the supply and delivery charges that specific Longmeadow residents have faced. “As a result, homeowners who are working to meet the state goals of transitioning to using more electricity and less fossil fuel, are faced with the much higher than anticipated utility bills.”

An analysis from the Department of Energy Resources found that heating oil was the most expensive fuel to heat an average household last winter, costing $2,023 to get through the 2022-23 winter. Propane customers paid $1,492 while natural gas heat cost $907 for the heating season. Electric heating, primarily electric baseboard heating, cost an estimated $1,080, though DOER said that also “reflects the smaller average home size for units that heat with electric resistance (baseboard) heat.”

For this winter, DOER estimated that heating with oil would cost $2,220, up 10 percent; that propane heat would cost $1,606, up 8 percent; that natural gas heat would cost $911, down 0.5 percent; and that electric heat would cost $862, down 20 percent.

The federal government also is keeping an eye on the burden that energy bills put on household budgets. When the U.S. Department of Energy announced Tuesday morning that 17 energy improvement projects in rural or remote areas (the nearest to Massachusetts is a project in Maine) would receive a total of $366 million in federal funding, a DOE official said that energy burden was one of the things the department considered when choosing projects to fund. The DOE official said that energy costs are 33 percent higher, on average, in rural and remote parts of America.

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest

UMass graduation speaker Colson Whitehead pulls out over quashed campus protest UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor

UMass student group declares no confidence in chancellor Four Rivers Climate Club organizes litter cleanup, panel on environmental activism

Four Rivers Climate Club organizes litter cleanup, panel on environmental activism