Finding joy in art: New exhibit at Augusta Savage Gallery celebrates the Black community

| Published: 11-10-2021 7:04 PM |

Like millions upon millions of people across the world, Eesha Suntai was horrified by the murder in May 2020 of George Floyd, who died after former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes during an arrest for passing a $20 counterfeit bill.

The New York artist responded in part with “Plight of the Black Man,” a painting that depicts the head and neck of a Black man, who stares back at the viewer as several disembodied hands float around his face, some pointing at him, one cupping his cheek — while another, in a white glove, grips his throat in a chokehold.

Suntai’s painting became part of a virtual exhibit, “Breathing While Black,” that was staged last fall by the Augusta Savage Gallery at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in response to Floyd’s murder and the protests that erupted in its wake.

That painting in turn caught the eye of Alexia Cota, interim director at Augusta Savage, who was interested in seeing more of Suntai’s work.

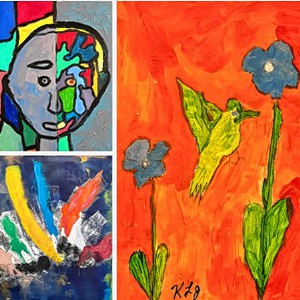

Fast-forward to fall 2021, and the gallery is now hosting “Dear Black Child,” an exhibit featuring numerous oil and acrylic paintings by Suntai that showcase the artist’s bold use of color and her earthy, expressive portraits of people. It’s her first solo exhibit and her first show outside the greater New York City area (she grew up in Queens, N.Y.).

As Suntai describes it, “Dear Black Child” is in part a reflection of her own experiences, something of a commentary on Black culture and the post-George Floyd racial dynamic, and an effort to capture the joy and innocence of young people who haven’t yet faced the hardships and conflicts that can come with adulthood.

“In essence, this is me telling the story of my life, my experience growing up Black in America, and also what I’ve seen happen to other people,” Suntai said during a recent interview at the gallery. “It’s also a way of showing Black men in particular and the trouble they have to deal with, the challenges they can face.

“It’s also kind of like a love letter to myself, about loving who you are,” she added.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

Greenfield man arrested in New York on murder charge

Greenfield man arrested in New York on murder charge

Man allegedly steals $100K worth of items from Northampton, South Deerfield businesses

Man allegedly steals $100K worth of items from Northampton, South Deerfield businesses

Joannah Whitney of Greenfield wins 33rd annual Poet’s Seat Poetry Contest

Joannah Whitney of Greenfield wins 33rd annual Poet’s Seat Poetry Contest

From a portrait of a young cousin with a beaming smile, to another based on a scene from the 1975 movie “Cooley High” (a coming-of-age story about four young Black men), to something of a self-portrait that depicts a Black woman crowned with a huge circle of flowers, Suntai’s paintings offer a mix of realist and hyper-realist portraiture that seem to welcome viewers into their different worlds.

“Her portraits really capture the people in those paintings, their energy and personality,” said Cota, who added that after she and former Augusta Savage Gallery Director Terry Janoure saw Suntai’s “Plight of the Black Man” last year, it was “an absolute no-brainer to invite her here to do her own show.”

The exhibit, which runs through Dec. 10, also reflects a renewed commitment Suntai made to painting beginning about five years ago. She says that after she received her bachelor’s degree in fine arts in 2012, from Adelphi University on Long Island, economic needs soon pulled her into the banking world for a number of years, a period during which she “didn’t really pick up a paintbrush.”

But in 2016, she moved on to less stressful work and, she said, “rediscovered my love of painting. I made it my mission to create paintings with a lot of color. My older paintings were darker.” She has since exhibited her work in many group shows in the New York City area.

In renewing her artwork, she also reflected more on her own life and being a Black woman in general. In “4C Struggles,” a Black woman is trying to comb her hair; she seems to glance up at a huge mass of flowers encircling her head, wondering what’s going on.

As Suntai explains, 4C is a term used to describe the type of hair many people of color have, hair that is naturally wiry or kinky. Society has conditioned many Black women in particular to believe they need to flatten or curl their hair, she said — thinking that she fell prey to herself in the past.

The painting, then, is in part “about accepting myself, accepting that my hair is OK as it is,” said Suntai. The woman in the portrait “doesn’t realize the flowers are beautiful. She’s not understanding the beauty that God has blessed her with already.”

Another painting, “Malik,” is based on her nephew when he was in high school. To create the work, an oil on hardboard painting of a young man wearing a dark blue sweatshirt and a backpack, Suntai put down a base layer of bright color and then built on that, leaving a faint yellowish glow behind him: “I wanted that bit of halo around him because he’s a representation of youth and innocence.”

Some of her work in the UMass exhibit is more directly topical. “Do We Matter?” depicts a handful of Black men and women at a rally — a Black Lives Matter sign floats in the background — and some of the people look angry, while others are crying.

In “National Hero,” a woman wears surgical gloves, a face mask and a long cape, a la Superwoman; she holds what looks like a container of cleanser or disinfectant in one hand.

“She may be a cleaning lady, she may be doing janitorial work, she may work in a hospital, but she’s one of those people who put their lives on the line to protect others,” Suntai said.

Two of her most appealing paintings are based on two of her young cousins. “Kendall” presents a young girl wearing sunglasses and a glowing, slightly gappy smile — the look of a kid who’s completely unselfconscious about her appearance. In “Black Boy Joy,” two little boys wearing dress sweaters look seriously at the viewer; the one on the left — Suntai’s cousin — points his right index finger straight up.

“I don’t know what he meant by that but I liked it,” said Suntai, who based the painting on a photograph. “And I like the sense of ‘You’re looking at me and I’m looking at you’ that I get from” that painting.

More recently, Suntai has been creating more abstract paintings, as well as still-lifes, using color as the basis for exploration. She’ll continue with her portraiture work, too, as she works to build on her UMass exhibit: “I feel blessed to have this opportunity.”

Proof that it’s never too late: Solo exhibit and free workshops honor the late Frederick Gao, a Belchertown resident who became a painter in his last five years

Proof that it’s never too late: Solo exhibit and free workshops honor the late Frederick Gao, a Belchertown resident who became a painter in his last five years Self-expression on display: ServiceNet members’ artworks on view at Greenfield Public Library through end of May

Self-expression on display: ServiceNet members’ artworks on view at Greenfield Public Library through end of May Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week