Latest News

Beacon Hill Roll Call: April 8 to April 12, 2024

Beacon Hill Roll Call: April 8 to April 12, 2024

My Turn: Saving planet Greenfield

My Turn: Saving planet Greenfield

$50K allocated for Poet’s Seat Tower sandblasting as officials mull vandalism prevention

GREENFIELD — Following an affirmative vote by City Council this week, $50,000 will go toward sandblasting graffiti off of Poet’s Seat Tower, where vandalism has proven to be a persistent problem.Department of Public Works Director Marlo Warner II said...

PHOTOS: Convening for a good cause

Most Read

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

Orange man gets 12 to 14 years for child rape

Orange man gets 12 to 14 years for child rape

Greenfield Police Logs: April 2 to April 8, 2024

Greenfield Police Logs: April 2 to April 8, 2024

One Greenfield home invasion defendant up for bail, other three held

One Greenfield home invasion defendant up for bail, other three held

Fire scorches garage on Homestead Avenue in Greenfield

Fire scorches garage on Homestead Avenue in Greenfield

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Editors Picks

Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history

Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history

PHOTO: Double eagle

PHOTO: Double eagle

North County Notebook: April 20, 2024

North County Notebook: April 20, 2024

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Sports

High schools: South Hadley softball holds off Frontier rally for 5-4 victory (PHOTOS)

A day after completing a comeback victory over Greenfield, the Frontier softball team looked like it had another rally in the works on Friday against South Hadley.The Tigers held a 1-0 lead going into the sixth inning when the Redhawks rallied,...

Opinion

Jessica Zhang: Weigh your choices — Solar power a better alternative

In his recent letter [“‘No’ means higher energy prices,” Recorder, March 26] Jim Bates is right that fossil fuels have powered societies across the globe — nobody disputes that. It’s the reality of pollution and carbon buildup in the atmosphere that...

Gary Seldon: Solar Roller Earth Day River Ride

Gary Seldon: Solar Roller Earth Day River Ride

Columnist Johanna Neumann: Reaping the rewards of rooftop solar

Columnist Johanna Neumann: Reaping the rewards of rooftop solar

My Turn: Let’s leave miracle of trees well enough alone

My Turn: Let’s leave miracle of trees well enough alone

Business

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

TURNERS FALLS — Members of the Snow family have added another golf course to their portfolio and have already begun work on cosmetic improvements.Kyle and Kelly Snow, along with Kyle’s parents Edward Snow Jr. and Kerrilynn Snow, bought the Thomas...

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Patrons can ‘walk down memory lane’ at Sweet Phoenix’s new Greenfield location

Patrons can ‘walk down memory lane’ at Sweet Phoenix’s new Greenfield location

Arts & Life

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

A lot can change in 20 years: Presidents and other politicians come and go, new cultural fads and technologies emerge, clothing styles morph, and music and movies take on different dimensions.In these parts, one tradition hasn’t changed. Since 2005,...

Obituaries

Judith Fuhring Seelig

Judith Fuhring Seelig

Amherst, MA - Judith (Fuhring) Seelig passed away peacefully at Cooley Dickinson Hospital on October 21, 2023 after a brief illness. She was surrounded by friends and family with music and ... remainder of obit for Judith Fuhring Seelig

Richard F. Delphia

Richard F. Delphia

Ashfield, MA - Richard F. Delphia, 84, passed away at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield on Tuesday, April 16, 2024, of complications from a fall. Dick was born in Ludlow, MA on Aug... remainder of obit for Richard F. Delphia

Mary Lou Barton

Mary Lou Barton

Leyden, MA - Mary Lou (Johnson) Barton, 74, of Leyden MA, took the Lord's hand on April 16, 2024, surrounded by her loving family at home. She was born in Brattleboro, VT on September 7, 19... remainder of obit for Mary Lou Barton

Judith M. Lively

Judith M. Lively

Greenfield, MA - Judith Mae (Phillips) Lively, 85, of Wells St., passed away on Tuesday April 9, 2024. Judy was born in Greenfield on June 5, 1938 the daughter of Walter and Mildred (Ch... remainder of obit for Judith M. Lively

Connecting the Dots: In what world do you want to live?

Connecting the Dots: In what world do you want to live?

‘Glamping’ resort developers look to curb traffic, sewer concerns in Charlemont

‘Glamping’ resort developers look to curb traffic, sewer concerns in Charlemont

As emergency action plan is crafted, Tree House to maintain 1,500 capacity for summer

As emergency action plan is crafted, Tree House to maintain 1,500 capacity for summer

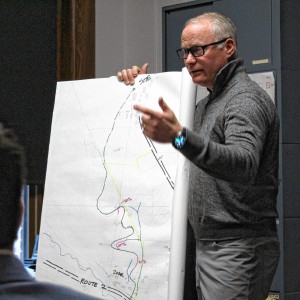

MassDOT shares plans for Church Street bridge replacement in Erving

MassDOT shares plans for Church Street bridge replacement in Erving

Proposed Colrain solar bylaw changes would add definitions, expand site plan reviews

Proposed Colrain solar bylaw changes would add definitions, expand site plan reviews

Deerfield voters to decide 8 capital projects at Town Meeting

Deerfield voters to decide 8 capital projects at Town Meeting

Shelter money fading, but ‘not at the end of the line’

Shelter money fading, but ‘not at the end of the line’

Softball: Franklin Tech’s Hannah Gilbert holds Hopkins to two hits, leads Eagles to 7-1 victory (PHOTOS)

Softball: Franklin Tech’s Hannah Gilbert holds Hopkins to two hits, leads Eagles to 7-1 victory (PHOTOS) Keeping Score with Chip Ainsworth: What’s ahead for Greg Carvel’s crew?

Keeping Score with Chip Ainsworth: What’s ahead for Greg Carvel’s crew? High schools: Abigail Schreiber’s hit propels Frontier softball past Greenfield, 3-2

High schools: Abigail Schreiber’s hit propels Frontier softball past Greenfield, 3-2 Baseball: Frontier handles Greenfield 12-2 in five-inning victory (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Frontier handles Greenfield 12-2 in five-inning victory (PHOTOS) Mitch Speight and Joan Marie Jackson: City should follow constitutional ruling on property takings

Mitch Speight and Joan Marie Jackson: City should follow constitutional ruling on property takings Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many

Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near

Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near Sounds Local: Spring is singer-songwriter season: A host of local performers celebrate new work

Sounds Local: Spring is singer-songwriter season: A host of local performers celebrate new work Crunch time for matzo: An easy-to-make sweet treat that’s Passover Seder-friendly

Crunch time for matzo: An easy-to-make sweet treat that’s Passover Seder-friendly