Native Insight: A hole in the Great Beaver myth

| Published: 06-24-2018 3:00 PM |

Twists and turns. Always twists and turns to the Great Beaver origin tale of an iconic local mountain range. The question is, what are the sources?

What remains consistent, though, is the site of the Pocumtuck Range, the giant Pleistocene beaver and the super-human Eastern Algonquian earth-shaper or transformer figure Hobomock, who’s known by other names among various related Northeastern dialects. What’s constantly changing is the motive for killing the beast and the lesson to be learned from the act that left behind a distinctive range, which to this day from many directions resembles the carcass of the petrified giant beaver of indigenous lore. Though the genesis and 19th-century resurrection of this well-known story can be loosely tracked, it remains difficult to make sense of at times.

Deacon Phineas Field, a Northfield native who settled in Charlemont, is generally credited with bringing this deep-history folktale out of mothballs around 1870. As an active local historian and charter member of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Field had obviously discussed the story with the membership there before it was published in the organization’s “Proceedings.” Where Field heard the tale is anyone’s guess, but it must have come from his gene pool or maybe the neighborhood of his Northfield or Deerfield kinfolk, told as a fanciful Native American origin myth of Mount Sugarloaf and its Pocumtuck Range running north-south from Old Deerfield to the South Deerfield-Whately line.

Field’s recounting of the tale underscores two interesting facts about beavers in Franklin County, which before colonial settlement would have been ubiquitous but had disappeared by Field’s time, having been wiped out by 17th-century trapping in local terrain that had been largely deforested by the mid-19th century. Clearly beavers were themselves creatures of myth by the time Field published his story of this giant furbearer wreaking havoc with fish and people in its Mount Tom basin beaver pond, bordered in the north by Sugarloaf and Mount Toby. Then, when the fish were few, he was said by Field to have come ashore to devour Native Americans. Thus, a powwow was convened and Hobomock was summoned to kill the beaver, which the legendary super-human transformer figure of Native lore bludgeoned to death with a sharp blow to the neck.

A similar tale was retold by Deerfield historian George Sheldon in his 1895 book, “A History of Deerfield, Massachusetts,” which was vaguer about the reason for dispatching the beast, citing nonspecific “continued depredations,” which faintly suggests agreement with his colleague and friend Field’s version. The beaver’s carcass was visible as an identifiable landmark once glacial Lake Hitchcock — extending approximately from Lyndonville, Vt., to Middletown, Conn. — drained to form the fertile Connecticut Valley some 14,000 years ago.

This popular, colonial version of the tale was retold with attribution to Field by Edward P. Pressey, author of the 1910 “History of Montague.” By this time, the Montague historian slightly embellished the tale by being more specific than either Field or Sheldon. Pressey wrote: “The great beaver preyed upon the fish of the long river. And when other food became scarce, he took to eating men out of the river villages.”

Now, right here and now, it must be said that beavers are not and never have been meat- or fish-eaters. They are herbivores, eating tree bark and plants, not pond critters such as fish, frogs, snakes, salamanders, ducklings or any other wetland creatures. They are plant-eaters, plain and simple, and so, according to cursory online research, were their giant Pleistocene beaver cousins.

I find it odd that I have never seen this potential myth-dispelling fact stated anywhere in print associated with the Great Beaver Tale. And to be honest, me myself, an outdoor columnist for nearly 40 years and an outdoorsman, hunter and fisherman for even longer, wasn’t sure of that fact and never checked until my naturalist brother-in-law from Maine raised the issue over the weekend. Just one simple query by him really got my wheels spinning. Told the details of the tale, the professor emeritus suggested that it made no sense because, “I don’t think beavers eat meat or fish, and the Indians surely would have known that.” Though quite sure, even he, an astute observer and nature lover for almost all of his 73 years, didn’t know that beavers ate no fish or meat.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Greenfield man arrested in New York on murder charge

Greenfield man arrested in New York on murder charge

Former Leyden police chief Daniel Galvis charged with larceny

Former Leyden police chief Daniel Galvis charged with larceny

Judge dismisses case against former Buckland police chief

Judge dismisses case against former Buckland police chief

Greenfield Police Logs: April 9 to April 17, 2024

Greenfield Police Logs: April 9 to April 17, 2024

Millers Meadow idea would ‘completely transform’ Colrain Street lot in Greenfield

Millers Meadow idea would ‘completely transform’ Colrain Street lot in Greenfield

Greenfield’s Court Square to remain open year-round for first time since 2021

Greenfield’s Court Square to remain open year-round for first time since 2021

Bingo! The seed of inquiry had been planted in my curiosity. When he retired to bed for the night, I couldn’t resist a quick online search for clarification before I called it a night. I sat at my computer and, yes, sure enough, beavers and their ancient predecessors that were closer in size to a large black bear, were herbivores. No question, indigenous pre-contact people would have known this fact, which strongly suggests that such a tale would not have come from a culture that valued the beaver greatly for its pelt and meat (beaver tail was a delicacy). Such a ridiculous tale just wouldn’t fly. Perhaps it would have worked as a silly comedy used by storytellers to lift the spirits and break serious, somber fireside moods with laughter and giggles. But such a story would never have survived as a serious, deep-time, lesson-teaching creation tale explaining a sacred, ceremonial landscape, especially a distinctive, serious Connecticut Valley landmark.

Now, of course, that is not to say that new interpretations of the Great Beaver Tale being floated in print these days are the tales, word-for-word, stanza-by-stanza, of a selfish, hoarding beaver killed as a warning against greed and refusal to share. That may or may not have been the lesson of the tale told before Norse, Dutch, French and English invaders stepped upon our eastern shores; before new occidental religions worked to conquer, kill and convert Native Americans and erase their languages and culture. With the erasure of these rich, lyrical, oral tales memorized in verse and maybe even song, went the fascinating tales of cultural heroes and villains, of medicinal-plant knowledge, the enthralling creation stories that could mesmerize listeners for days at a time. Truth be told, the tale that was recited and well known prior to European arrival to our shores will, sadly, never be recovered verbatim.

Nonetheless, isn’t it fun to give it our best shot? Fun to explore and reassemble what’s left of our “Beaver Hill” people’s deep-history tales? Fascinating to ponder this enthralling tale’s moral lessons, sequence and tone? Still, the shameful fact is that the old, original tale has vanished, and new ones cannot be documented or proved.

Tales of the land live forever when told in view of the landform or feature being described. However, these narratives soon fade beyond recognition when tellers and listeners lose their daily physical attachment to the landscape. Why would people lionize something like the Pocumtuck Range when they have been far removed for centuries and no longer live with it, and are instead greeted daily by infinitely more familiar landscapes called home?

We all know the saying: “Home is where the heart is.” Well, that also applies to the mind and its creative powers, which are vividly and firmly rooted in a sense of place.

]]>

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here

Speaking of Nature: Indulging in eye candy: Finally, after such a long wait, it’s beginning to look like spring is here Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock

Celebrating ‘Seasonings’: New book by veteran preacher and poet, Allen ‘Mick’ Comstock Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces

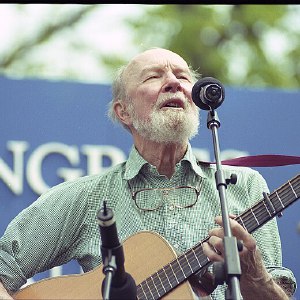

Faith Matters: How to still the muddy waters of overthinking: Clarity, peace and God can be found in the quiet spaces A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6

A time for every purpose under heaven: Free sing-a-long Pete Seeger Fest returns to Ashfield, April 6