Local residents recall JFK assassination 60 years on

| Published: 11-21-2023 2:04 PM |

Riding the commuter rail home to Haverhill from Boston in the early afternoon of Nov. 22, 1963, David Lewis couldn’t help but notice all the American flags he passed had been lowered to half-staff. This was peculiar, he recalled, “because they weren’t when I left that morning.”

This was decades before everyone had a cellphone and information superhighway in their pocket, so there was little way 20-year-old Lewis could have known his president, John F. Kennedy, had been shot and killed in Dallas, Texas. The assassination sent shock waves around the world and reshaped American culture in a way that is still felt today. Millions of people liken the event to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, in that anyone old enough to form memories remembers exactly what they were doing when they heard the tragic news that fateful day.

Lewis, who moved to Greenfield decades ago and chairs its Republican Town Committee, recalled he got off the train at the Haverhill station and saw a man he did not know leaning against a car.

“He ran up to me and grabbed me by the lapel saying, ‘They murdered him! They murdered him!’” Lewis said. “I thought the guy was completely deranged.”

Lewis said he shoved the man away and trotted a few blocks home, where he went to the kitchen to make himself lunch, but not before turning on the television. It was then that he saw legendary journalist Walter Cronkite with tears in his eyes. Lewis went back and forth between the kitchen and the living room for a few minutes before Cronkite announced to the world that Kennedy was dead.

“It was different, that’s for sure,” Lewis said. “And of course nothing like that had ever happened in my lifetime.”

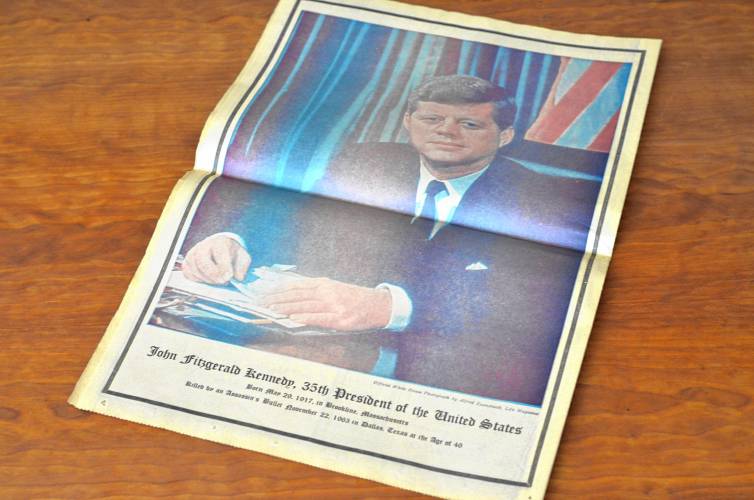

He said he and his father, who worked at a post office, watched the televised funeral days later and he remembers marveling at all the foreign dignitaries in attendance. Officials from nearly 100 countries visited the United States to pay their respects to its 35th president.

Earlier in the morning on Nov. 22, 1963, Kennedy had been in Fort Worth, where he gave a planned speech at the Chamber of Commerce breakfast. He then addressed a crowd of thousands with an unscheduled speech outside in the rain before heading to Carswell Air Force Base to take a plane to Dallas. The president disembarked Air Force One at 11:38 a.m. and left in a motorcade for Dallas Trade Mart, accompanied by first lady Jackie Kennedy, Texas Gov. John Connally, Connally’s wife Nellie and Secret Service agent Roy Herman Kellerman in a roofless 1961 Lincoln Continental driven by Secret Service agent William Greer.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

Ethics Commission raps former Leyden police chief, captain for conflict of interest violations

Ethics Commission raps former Leyden police chief, captain for conflict of interest violations

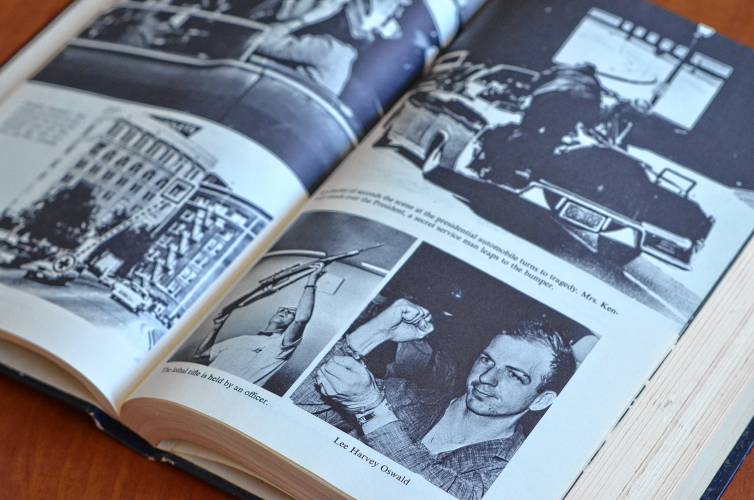

The vehicle entered Dealey Plaza at 12:30 p.m. and the assassination was captured on now-famous footage filmed by Abraham Zapruder on his 8mm Bell & Howell home movie camera, which like all home movie cameras in those days, did not have sound capability. According to the Warren Commission, a 24-year-old former Marine named Lee Harvey Oswald was on the sixth floor of the southwest corner of the Texas School Book Depository and fired three shots in 5.6 seconds with an Italian-made 6.5mm Mannlicher Carcano rifle he had bought for $12.78 and received in the mail. Reportedly, the first bullet missed any target, but the second and third struck Kennedy. Greer was criticized for slowing down to a near-stop after Kennedy was initially struck and accelerating only after the fatal shot had hit the commander in chief. Kennedy was driven to Parkland Memorial Hospital, a few minutes away, where he was pronounced dead at 1 p.m.

While one million people lined the street as the horse-drawn caisson carrying Kennedy’s body traveled from the U.S. Capitol to St. Matthew’s Cathedral and then to internment at Arlington National Cemetery, an estimated 180 million people worldwide watched the Nov. 25 procession and funeral on television.

One of those people was 11-year-old Virginia “Ginny” Desorgher, now Greenfield’s mayor-elect, and her family in eastern Massachusetts. Desorgher recalls the solemn event, complete with Black Jack, the riderless horse with boots reversed in its stirrups to symbolize a fallen leader.

“I remember it like it was yesterday. I remember what Jackie had on. I remember her family, Caroline and John-John,” she said, referring to JFK’s daughter, now the U.S. ambassador to Australia, and son, John F. Kennedy Jr. “We were [in front of the TV] all day. It was just such a loss.”

Desorgher recounted that she was at St. Joseph School in Needham days earlier when someone came to the classroom to speak to her sixth grade teacher, Sister Frances Therese, who had been reading the students a story.

“I knew from the way she conducted herself that it was very sad and very serious,” the incoming mayor recalled. School was dismissed early that day and all students walked home to be with their families.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen my mother cry so much,” she said. “It was just so sad.”

The parents of Ray Younghans, who now chairs the Orange Republican Town Committee, reacted differently and did not talk about it much.

“They were just very quiet about it. It was a different generation,” he recalled. “The feeling was, ‘It couldn’t have happened here,’ but it did.”

Earlier in the day, 17-year-old Younghans had been in Mr. Kalogerakis’ history class at West Babylon High School on Long Island when the announcement came over the public address system. He said the school day continued but students kept to themselves. Elsewhere in New York, Ferd Wulkan was finishing up his school day in the Bronx when word started spreading in homeroom that the president had been assassinated. He went home to Manhattan, where his parents were glued to the radio listening to the news. They had recently purchased a television set but seldom used it.

Two days after Kennedy was killed, the world watched as Oswald was fatally shot by nightclub owner Jack Ruby while in police custody.

“What I remember is that whole week, actually — both the JFK assassination and Oswald — and thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, what’s the country coming to that everybody’s getting shot?’” Wulkan, of Montague, recalled. “It was an eye-opener and wake-up call and I think a lot of people got radicalized, in a sense, by that assassination.”

Wulkan, a member of Franklin County Continuing the Political Revolution, a multi-issue grassroots organization that champions progressive causes, said to a lot of young people Kennedy represented a break from the unsavory archetype of a commander in chief. He also said the government’s mishandling of the case in the immediate aftermath has justifiably generated conspiracy theories about what really happened and ushered in the era of dissent.

“I feel like it’s still not really resolved,” Wulkan said of the assassination, which occurred when he was 15.

This seed of curious doubt was planted a couple of years after the shooting by a guest speaker Wulkan’s high school invited as part of a program known as The Forum, which hosted different speakers to address the student body. That particular guest speaker was Mark Lane, an attorney and Democratic state legislator regarded as the first high-profile person to question the official story of what transpired on Nov. 22, 1963. He maintained that the account of the JFK assassination was not entirely factual, or at least not the whole story.

“That never occurred to me,” Wulkan said. “And that made a huge impression on me and, I think, on a lot of people.”

Samuel J. Redman, a history professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the director of its Public History Program, said JFK’s death and Cronkite’s future editorializing on the Vietnam War fueled what historians call “the credibility gap” — a term used to describe public skepticism and any apparent difference between what is said or promised and what is true.

“Culturally and socially, it was a big moment,” Redman said. “I’ve heard some people describe it as a death of innocence.”

He said it is fair to pick at threads and ask questions when an authority’s official narrative seems fishy.

“There needs to be room, I would say, for different interpretations of events and, frankly, that’s how professional historians do history,” he said, adding that people often want to rationalize violence, which is inherently irrational.

Redman also said the JFK assassination had a significant impact on the culture of the Secret Service, which was forced to rethink certain protocol, such as allowing the president to ride in a roofless vehicle.

Kennedy’s death also bolstered the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 as well as the ratification of the U.S. Constitution’s 25th Amendment, which deals with presidential succession and disability. It clarifies that the vice president becomes president if the president dies, resigns or is removed from office through impeachment, and establishes how a vacancy in the office of the vice president can be filled.

“One of the big debates we always have is ... why and how LBJ, JFK’s successor, was so successful with so many legislative victories,” Redman said. “LBJ was a notorious tough guy and almost thugish in the way that he would sort of crack skulls ... to get [bills] through.”

Redman, 38, was born two decades after the assassination but said his mother was in middle school and recalls her teacher wheeling a television into the classroom on Nov. 22, 1963, to watch the news. This was extremely uncommon at the time but the shooting initiated four days of non-stop live television news coverage. Redman compared the assassination to 9/11, the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986 and other world-changing events that Americans watched in real time.

“In some ways the Kennedy assassination is the first iteration of that,” he said.

Reach Domenic Poli at: dpoli@recorder.com or 413-930-4120.

What are the protocols for emergency transport of infants?

What are the protocols for emergency transport of infants? Frontier Regional School students appeal to lower voting age

Frontier Regional School students appeal to lower voting age