Joannah Whitney of Greenfield wins 33rd annual Poet’s Seat Poetry Contest

GREENFIELD — After a few years submitting her work to the annual Poet’s Seat Poetry Contest, Greenfield poet and freelance writer Joannah Whitney placed first among the contest’s adult finalists Tuesday night at the Greenfield Public Library. The...

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

BERNARDSTON — The Windmill Motel was sold at auction earlier this month to a private out-of-state lender.The motel at 497 Northfield Road, which was opened by Kolman Nemes in 1981, was bought for $750,000 on April 10, according to Marianne Sullivan,...

Most Read

Greenfield man arrested in New York on murder charge

Greenfield man arrested in New York on murder charge

Man allegedly steals $100K worth of items from Northampton, South Deerfield businesses

Man allegedly steals $100K worth of items from Northampton, South Deerfield businesses

Greenfield Police Logs: April 9 to April 17, 2024

Greenfield Police Logs: April 9 to April 17, 2024

Former Leyden police chief Daniel Galvis charged with larceny

Former Leyden police chief Daniel Galvis charged with larceny

Shea Theater mural artist chosen out of 354 applicants

Shea Theater mural artist chosen out of 354 applicants

Millers Meadow idea would ‘completely transform’ Colrain Street lot in Greenfield

Millers Meadow idea would ‘completely transform’ Colrain Street lot in Greenfield

Editors Picks

Sounds Local: A rock circus returns to Turners Falls: The Slambovian Circus of Dreams brings the fun Friday night at the Shea

Sounds Local: A rock circus returns to Turners Falls: The Slambovian Circus of Dreams brings the fun Friday night at the Shea

Monroe election sees no contests, some positions without candidates

Monroe election sees no contests, some positions without candidates

Business Briefs: April 26, 2024

Business Briefs: April 26, 2024

PHOTO: A valuable simulation

PHOTO: A valuable simulation

Sports

Country Club of Greenfield holding Youth Golf Camp June 24-27

The Country Club of Greenfield is holding its Youth Golf Camp from June 24-27. The camp will be capped at 25 children on a first come, first serve basis. The fee is $170 for the first family member and $140 for each additional family member. The camp...

High schools: Lilly Ross records 100th career hit in Franklin Tech’s win over Northampton

High schools: Lilly Ross records 100th career hit in Franklin Tech’s win over Northampton

Baseball: Wyatt Edes’ walk-off single lifts Frontier past Amherst 6-5

Baseball: Wyatt Edes’ walk-off single lifts Frontier past Amherst 6-5

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

High Schools: Jakhia Williams propels Turners girls track past Athol

High Schools: Jakhia Williams propels Turners girls track past Athol

Opinion

My Turn: April is second chance month

April is Second Chance Month, a time to focus on how our community can support our neighbors in central and western Massachusetts returning from incarceration.As attorneys with Community Legal Aid’s CORI/Re-Entry Unit, we see the life-changing power...

My Turn: Judgmental about malaise

My Turn: Judgmental about malaise

Ahmad Esfahani: Aiding and abetting and middle school angst

Ahmad Esfahani: Aiding and abetting and middle school angst

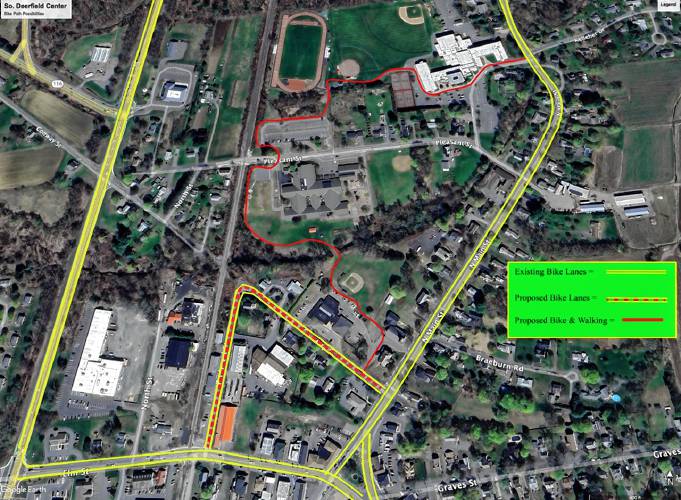

Greg Franceschi: Support bike lanes and walking paths in South Deerfield

Greg Franceschi: Support bike lanes and walking paths in South Deerfield

Laurie Benoit: Volunteers needed for cleanup of Buckland cemeteries

Laurie Benoit: Volunteers needed for cleanup of Buckland cemeteries

Business

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

SPRINGFIELD — As the Realtor Association of Pioneer Valley’s new CEO arrives to a Massachusetts housing market plagued by high prices and a lack of stock, he aims to work alongside elected officials to maximize the availability of different kinds of...

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Arts & Life

Rescuing food and feeding people: Rachel’s Table programs continue to expand throughout western Mass

My great-grandmother’s oak dining table has graced my kitchen ever since my parents built the house in the 1980s. Looking at it makes me happy. The table — actually, almost any table — signifies history, nourishment, family and community.The...

Obituaries

Constance Julia Dargis

Constance Julia Dargis

Constance Julia (LaMountain) Dargis Montague Center, MA - Constance "Connie" Julia Dargis, 98, formerly of Turners Falls MA, suffered an unexpected illness on November 13th and passed away peacefully on November 16, 2023 at the home of her ... remainder of obit for Constance Julia Dargis

John H. Stevens Jr.

John H. Stevens Jr.

John H. Stevens, Jr. Gill, MA - John H. Stevens, Jr., 69, of Main Road died Monday 4/22/24 at home. He was born in Greenfield on December 9, 1954, one of nine children of John H. and Evelyn (Bassett) Stevens. John worked as a papermaker... remainder of obit for John H. Stevens Jr.

Maryjean DelRosso

Maryjean DelRosso

Heath, MA - Maryjean (Sullivan) DelRosso passed away peacefully on April 19, 2024 at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield after a long illness. She is survived by her devoted husband, Joseph DelRosso. Maryjean is also survived by thr... remainder of obit for Maryjean DelRosso

Carol Butler Watelet

Carol Butler Watelet

Greenfield, MA - Carol (Virginia) Soucie Butler Watelet, 85, passed away suddenly and peacefully on April 20, 2024, joining the love of her life, Mr. Wonderful, Robert Watelet who passed away 2 years earlier. Carol was born on March 17,... remainder of obit for Carol Butler Watelet

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Advancing water treatment: UMass startup Elateq Inc. wins state grant to deploy new technology

Sunderland Public Library hosting 20th birthday party for its building

Sunderland Public Library hosting 20th birthday party for its building

Real Estate Transactions: April 26, 2024

Real Estate Transactions: April 26, 2024

Shelburne fair to explore energy-efficient options for homeowners

Shelburne fair to explore energy-efficient options for homeowners

Erving rejects trade school’s incomplete proposal for mill reuse

Erving rejects trade school’s incomplete proposal for mill reuse

Parents question handling of threat at Erving Elementary School

Parents question handling of threat at Erving Elementary School

Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis

Guest columnists Ellen Attaliades and Lynn Ireland: Housing crisis is fueling the human services crisis

William Strickland, a longtime civil rights activist, scholar and friend of Malcolm X, has died

William Strickland, a longtime civil rights activist, scholar and friend of Malcolm X, has died

Shutesbury voters to decide on battery storage, lighting bylaws

Shutesbury voters to decide on battery storage, lighting bylaws

A day to commune with nature: Western Mass Herbal Symposium will be held May 11 in Montague

A day to commune with nature: Western Mass Herbal Symposium will be held May 11 in Montague Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever

Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28 Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear