Latest News

Orange man gets 12 to 14 years for child rape

Orange man gets 12 to 14 years for child rape

Greenfield Police Logs: April 2 to April 8, 2024

Greenfield Police Logs: April 2 to April 8, 2024

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

GREENFIELD — More than a year after she was told her business would need to vacate its storefront in the former Wilson’s Department Store, Cleary Jewelers owner Kerry Semaski said she plans to keep her shop at its current location until July 2029...

15th annual NELCWIT fundraiser set for Thursday

GREENFIELD — The Friends of NELCWIT will hold the 15th annual “Power to Persevere” fundraiser on Thursday, and this year’s event will be the first to include a dance element.The celebration, set for 5 to 8 p.m. at the Guiding Star Grange on Chapman...

Most Read

Of nearly 180 canoes in River Rat Race, Zaveral/MacDowell team claims victory

Of nearly 180 canoes in River Rat Race, Zaveral/MacDowell team claims victory

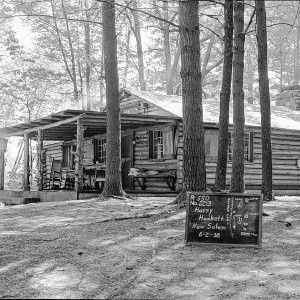

Wealth of historic Quabbin Reservoir photos available online

Wealth of historic Quabbin Reservoir photos available online

Greenfield seeks answers for $1M in state funds for Green River School

Greenfield seeks answers for $1M in state funds for Green River School

Proposed Greenfield tax fund would benefit elderly, residents with disabilities

Proposed Greenfield tax fund would benefit elderly, residents with disabilities

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

$427K to expand Camp Apex capacity in Shelburne

$427K to expand Camp Apex capacity in Shelburne

Editors Picks

Montague and Erving Notebook: April 15, 2024

Montague and Erving Notebook: April 15, 2024

PHOTOS: Blended learning

PHOTOS: Blended learning

Greenfield Notebook: April 15, 2024

Greenfield Notebook: April 15, 2024

North Quabbin Notebook: April 16, 2024

North Quabbin Notebook: April 16, 2024

Sports

High Schools: Two-run first inning propels Pioneer baseball past Turners

Turners Falls pitcher Joey Mosca did all he could to hold down a potent Pioneer lineup on Tuesday. Mosca gave up two runs in the first inning but settled in from there, not allowing a run the rest of the way while striking out six. The Turners bats...

Softball: Hannah Gilbert allows two hits as Franklin Tech knocks off Blackstone Valley, 7-3 (PHOTOS)

Softball: Hannah Gilbert allows two hits as Franklin Tech knocks off Blackstone Valley, 7-3 (PHOTOS)

UMass basketball: Matt Cross reportedly enters transfer portal

UMass basketball: Matt Cross reportedly enters transfer portal

Baseball: Sam Connors, Mahar get past Smith Academy for win No. 2 (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Sam Connors, Mahar get past Smith Academy for win No. 2 (PHOTOS)

Opinion

Maggie Baumer: Access to prosthetics and orthotics for physical activity a right, not a privilege

As one of the 5.6 million Americans living with limb loss and limb difference (LL/LD), I’m passionate about advocating for access to prosthetic and orthotic devices for physical activity, which are not typically covered by commercial insurance or...

Pat Hynes: Nuclear weapons bills need action

Pat Hynes: Nuclear weapons bills need action

Walt Gorman: Fed up

Walt Gorman: Fed up

Nikki Garrett: A joy to join in on Earth Day cleanup

Nikki Garrett: A joy to join in on Earth Day cleanup

My Turn: How to welcome a refugee family into your community

My Turn: How to welcome a refugee family into your community

Business

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

WHATELY — Tea Guys LLC must pay more than $2 million to a Baltimore tea company due to a breach of contract, a Franklin County Superior Court judge has ruled.The small business in Whately was sued last summer by Zest Tea LLC and had two bank accounts...

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Patrons can ‘walk down memory lane’ at Sweet Phoenix’s new Greenfield location

Patrons can ‘walk down memory lane’ at Sweet Phoenix’s new Greenfield location

Post-pandemic hardship prompts Between The Uprights closure in Turners Falls

Post-pandemic hardship prompts Between The Uprights closure in Turners Falls

Starbucks gets go-ahead from Greenfield Planning Board

Starbucks gets go-ahead from Greenfield Planning Board

Arts & Life

Crunch time for matzo: An easy-to-make sweet treat that’s Passover Seder-friendly

Passover begins this coming Monday night. This eight-day holiday means many things to many people: the survival of the Jewish people in the book of Exodus, the overall history of Judaism, and even the last supper of Jesus.This year Easter came more...

Obituaries

Matthew J. Osofsky

Matthew J. Osofsky

Greenfield, MA - Matthew J. Osofsky, 38, died Saturday 4/6/24 at the Baystate Medical Center in Springfield from injuries sustained from a car accident. He was born in Brooklyn, NY on Febru... remainder of obit for Matthew J. Osofsky

Sandra J. Niedzwiedz

Sandra J. Niedzwiedz

Erving, MA - Sandra J. Niedzwiedz, 69, of Goodell Place passed away unexpectantly at home on Wednesday, April 10, 2024. She was born in Greenfield on May 3, 1954, the daughter of Bernard an... remainder of obit for Sandra J. Niedzwiedz

Barbara M. Mahar

Barbara M. Mahar

Greenfield, MA - Barbara M. (Schotte) Mahar, 87, of Log Plain Rd., passed away on April 12, 2024 at Charlene Manor Extended Care Facility. A life-long resident of Greenfield, Barbara wa... remainder of obit for Barbara M. Mahar

Irving E. Mullette

Irving E. Mullette

North Adams, MA - Irving Mullette was born in North Adams, MA on April 23, 1938 to Eugene and (Vera) Christine Mullette. Out of high school, he went to East Coast Aero Tech Flying School, f... remainder of obit for Irving E. Mullette

Two local school advocates tapped to lead state’s new Small and Rural Schools Committee

Two local school advocates tapped to lead state’s new Small and Rural Schools Committee

With new library comes new venue for annual Poet’s Seat Poetry Contest

With new library comes new venue for annual Poet’s Seat Poetry Contest

Wheeling for Healing returns to South Deerfield to raise money for cancer treatment

Wheeling for Healing returns to South Deerfield to raise money for cancer treatment

My Turn: The pecking order revolution: Massachusetts’ fight for animal rights

My Turn: The pecking order revolution: Massachusetts’ fight for animal rights

With eye toward teaching firearm safety, Mahar’s Junior ROTC adding air rifles

With eye toward teaching firearm safety, Mahar’s Junior ROTC adding air rifles

Conway resident leading pilot program to help families facing financial ‘cliff effect’

Conway resident leading pilot program to help families facing financial ‘cliff effect’

Orange resident selected for governor’s Youth Advisory Council

Orange resident selected for governor’s Youth Advisory Council

High schools: Mahar softball can’t stay with Northampton in 20-6 loss (PHOTOS)

High schools: Mahar softball can’t stay with Northampton in 20-6 loss (PHOTOS) Spotlight on women in classical music: Brick Church Music Series’s season comes to a close, April 28-29, with Champlain Trio

Spotlight on women in classical music: Brick Church Music Series’s season comes to a close, April 28-29, with Champlain Trio Ready for their close-up: Pothole Pictures announces a season of curated film screenings, live music and $1 popcorn

Ready for their close-up: Pothole Pictures announces a season of curated film screenings, live music and $1 popcorn You’re up next: Western Mass open mic scene heats up post-pandemic

You’re up next: Western Mass open mic scene heats up post-pandemic Sounds Local: Fun for the whole family: Meltdown, a book and music fest for kids, returns to Greenfield this Saturday

Sounds Local: Fun for the whole family: Meltdown, a book and music fest for kids, returns to Greenfield this Saturday