Millers Meadow idea would ‘completely transform’ Colrain Street lot in Greenfield

GREENFIELD — The environmental nonprofit Greening Greenfield is seeking the city’s approval to plant a small forest and meadow along the perimeter of the former site of the Wedgewood Gardens mobile home park on Colrain Street.If approved, the group...

Greenfield’s Court Square to remain open year-round for first time since 2021

GREENFIELD — For the first time since 2021, Court Square will stay open to motorists year-round, closing only for special events that require pedestrian access.The city began seasonally closing Court Square to vehicles in 2021 when it adopted a pilot...

Most Read

Former Leyden police chief Daniel Galvis charged with larceny

Former Leyden police chief Daniel Galvis charged with larceny

My Turn: The truth about time spent on MCAS testing

My Turn: The truth about time spent on MCAS testing

GMLB, Newt Guilbault gets seasons underway Sunday (PHOTOS)

GMLB, Newt Guilbault gets seasons underway Sunday (PHOTOS)

Millers Meadow idea would ‘completely transform’ Colrain Street lot in Greenfield

Millers Meadow idea would ‘completely transform’ Colrain Street lot in Greenfield

Bulletin Board: Gary Tashjian, Cheri McCarthy win Twice As Smart Pickleball Tournament

Bulletin Board: Gary Tashjian, Cheri McCarthy win Twice As Smart Pickleball Tournament

Greenfield Girls Softball League opens its 2024 season (PHOTOS)

Greenfield Girls Softball League opens its 2024 season (PHOTOS)

Editors Picks

PHOTOS: Artsy and informative

PHOTOS: Artsy and informative

Greenfield High School Honor Roll, Third Quarter

Greenfield High School Honor Roll, Third Quarter

West County Notebook: April 23, 2024

West County Notebook: April 23, 2024

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Sports

High schools: Skyler Steele powers Frontier softball past Wahconah

It was a birthday to remember for Skyler Steele.The Frontier slugger smacked a home run and drove in five runs as the Redhawks cruised to a 15-3 victory over Wahconah in a Franklin County League West contest on Monday at Zabek Field in South...

Bulletin board: Landon Allenby, Lucas Allenby shine at USA Snowboard and Freeski Association Nationals

Bulletin board: Landon Allenby, Lucas Allenby shine at USA Snowboard and Freeski Association Nationals

Baseball: Athol outlasts Franklin Tech in nine-inning thriller (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Athol outlasts Franklin Tech in nine-inning thriller (PHOTOS)

GMLB, Newt Guilbault gets seasons underway Sunday (PHOTOS)

GMLB, Newt Guilbault gets seasons underway Sunday (PHOTOS)

Opinion

My Turn: National debt — A threat to our nation’s future

This is an update on a column I wrote last year about a threat to our future well-being: the national debt. To summarize, unless the debt crisis is brought under control soon the future will be much more difficult for you, your children, grandchildren...

Josie Silva: Voting age impacts voter turnout

Josie Silva: Voting age impacts voter turnout

Ferd Wulkan: Green schools are possible

Ferd Wulkan: Green schools are possible

Jessica Corwin: Lower voting age to strengthen democracy

Jessica Corwin: Lower voting age to strengthen democracy

Erika Heilig: Trump’s mug is not news

Erika Heilig: Trump’s mug is not news

Business

New Realtor Association CEO looks to work collaboratively to maximize housing options

SPRINGFIELD — As the Realtor Association of Pioneer Valley’s new CEO arrives to a Massachusetts housing market plagued by high prices and a lack of stock, he aims to work alongside elected officials to maximize the availability of different kinds of...

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

New owners look to build on Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club’s strengths

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Cleary Jewelers plans to retain shop at former Wilson’s building until 2029

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Tea Guys of Whately owes $2M for breach of contract, judge rules

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Primo Restaurant & Pizzeria in South Deerfield under new ownership

Arts & Life

A day to commune with nature: Western Mass Herbal Symposium will be held May 11 in Montague

This week’s feature is my 100th Home & Garden column for the Recorder, and I’m pleased to celebrate by sharing the plans of two local women who are organizing a remarkable event for anyone interested in learning about herbal remedies and natural...

Obituaries

Raymond E. Scott

Raymond E. Scott

Raymond E. "Ray" Scott Bunnell, FL - Raymond E. "Ray" Scott, 78, of Bunnell, Florida passed away August 15, 2023. Ray was born in Yonkers, NY March 19, 1945. He was the son of Allan and Selva (Barney) Scott. Ray moved to Buckland as a yo... remainder of obit for Raymond E. Scott

John Kubacki Jr.

John Kubacki Jr.

John Kubacki, Jr. Palm Bay, FL - John Kubacki, Jr., 75 years old, of Palm Bay, Florida died peacefully on Wednesday, April 17, 2024 surrounded by his loving family. He was born on October 8, 1948, the son of Irene and John Kubacki Sr. ... remainder of obit for John Kubacki Jr.

Frank Kelley

Frank Kelley

Keene, NH - Frank S. Kelley, 93 of Keene, N.H. formerly of Greenfield, Mass and Northfield, Mass. died Thursday (4-18-2024) at Cheshire Medical Center, Keene, N.H. He was born in Orange, Ma. on February 23, 1931, the son of Burton and M... remainder of obit for Frank Kelley

Diane H. Overstreet

Diane H. Overstreet

Greenfield, MA - Diane H. Overstreet (Glazier) of Greenfield succumbed to a short battle with cancer on Wednesday March 27th, 2024, at the age of 75. Born June 2nd, 1948, in Greenfield, Massachusetts to Warren and Bernice Glazier. D... remainder of obit for Diane H. Overstreet

Prescription drug take back day set for Saturday in 15 communities in Franklin, Hampshire counties

Prescription drug take back day set for Saturday in 15 communities in Franklin, Hampshire counties

Leverett Town Meeting voters will decide cease-fire call, budgets

Leverett Town Meeting voters will decide cease-fire call, budgets

Judge dismisses case against former Buckland police chief

Judge dismisses case against former Buckland police chief

$10K grant to build on Erving Public Library’s work with neurodivergent patrons

$10K grant to build on Erving Public Library’s work with neurodivergent patrons

Greenfield Police Logs: April 9 to April 17, 2024

Greenfield Police Logs: April 9 to April 17, 2024

Dual fundraisers in Bernardston to support The United Arc, Sgt. Jacob Garmalo Fund

Dual fundraisers in Bernardston to support The United Arc, Sgt. Jacob Garmalo Fund

Glass, sculpture artists to be featured at Salmon Falls Gallery

Glass, sculpture artists to be featured at Salmon Falls Gallery

Greenfield lifts cap on cannabis delivery operators as CCC guidelines expand access

Greenfield lifts cap on cannabis delivery operators as CCC guidelines expand access

Bulletin Board: Gary Tashjian, Cheri McCarthy win Twice As Smart Pickleball Tournament

Bulletin Board: Gary Tashjian, Cheri McCarthy win Twice As Smart Pickleball Tournament Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever

Speaking of Nature: ‘Those sound like chickens’: Wood frogs and spring peepers are back — and loud as ever Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28 Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many

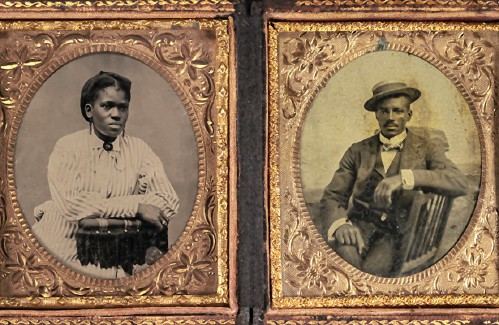

Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history

Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history