As I See It: Why do we hate our jobs?

| Published: 09-04-2023 7:00 AM |

We in America have been so busy warding off MAGA-fascism that we forget that, once we are safe from fascism, we are snugly back in the arms of capitalist (technically “liberal”) democracy. Safe from Trump’s fascism, we will still be hating our jobs under capitalists. We hate our jobs so much that, if the end of the world came today, our first thought might be: “Thank God, I don’t have to go to work tomorrow!”

So, how much do we hate our jobs? Per Bruce Feiler at MSNBC today (June 2), 70% of Americans are “unhappy” with their jobs and three-quarters of them plan to change their jobs this year; Feiler adds “9 out of 10” workers would give up one-quarter of their income for “more meaningful jobs.” Our job-hating is so widespread that it is listed as one of the “anxiety disorder” mental illnesses. Our very livelihood is a disease; how more horrible can it get?

But, interestingly, many Americans also confess their love of “the work I do.” Asked why they hate their work, they protest: “I love what I do. It’s the job I hate.” Obviously “work” and “jobs” are two different realities. But many of us are somewhat confused because our jobs are often cloaked as our “work” and our work is defined by our job.

Long before jobs were created in America — an imperative of a capitalist society that needs to hire “people” to fill jobs — frontier Americans knew only work, not jobs. Poor people, through the Dust Bowl, looked for “work” to do, not jobs. Work, not yet contaminated by jobs, was held so noble and obligatory that early Americans believed that those who do not work, as Scripture says, should not eat. Jamestown’s famous town motto was: “He that doesn’t work doesn’t eat.” Even today, we look down on those on welfare as loafers who avoid their share of work.

In our habit of mind in a capitalist state of mind, now, job is work and work is job. When the cranky comics character “Shoe” says, “In my dreams, I don’t have to work,” he is directing his loathing toward his job, not work. (As a newspaperman, we assume he loves his work). New York Times columnist Jonathan Malesic writes that “Work is our highest good.” But how do we attain our “highest good” with our work? He says: “Do your job.” Obviously, he confuses work and job. You feel good about yourself with your work as it is of the “highest good,” but you get depressed when you have to “do your job.” If you are a garment-factory worker, the clothes you stitch up keep many people warm and happy, but in your job as a garment worker at a sweatshop, you are reduced to a wretched minion in Hell.

It’s imperative then that we understand the differences between “work” and “job” in order to understand reasons for America’s job-hate.

WORK is what we need to do as Humanity to live together and as individuals to express our personality and talent while contributing to the community of all, working together toward the common goal of peace and harmony, not to mention survival and comfort.

No one is immune from this duty and shared labor as a member of society and humanity. In an honest society, like Japan, no one, not even the rich, avoids work. No question, everyone must work and do his “duty” to society and community. We work as carpenters, farmers, miners, fishermen, columnists and reporters, teachers, engineers and scientists, doctors and nurses, musicians, painters, and whatever else our personal talent and inclination call for, so that the whole community lives in comfort and peace.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

‘I have found great happiness’: The Rev. Timothy Campoli marks 50 years as Catholic priest

‘I have found great happiness’: The Rev. Timothy Campoli marks 50 years as Catholic priest

Formed 25,000 years ago, Millers River a historic ‘jewel’

Formed 25,000 years ago, Millers River a historic ‘jewel’

In this notion of work, everyone works and everyone benefits from their work together as we work for ourselves and for all at the same time, everyone working and everyone benefiting from their work. Whether in fair competition (like frontier America) or in cooperation (like the Amish), this type of society and community is what every good nation strives to become and, actually, all utopias look like this.

JOB, on the other hand, is our work that is standardized and uniformized into identical units within the Capitalist System. Work is done by human beings, but job is done by machines and processes, and job-holders are constantly replaced by cheaper competitors in machines (AI) and processes all the time.

If work is something we do for ourselves, job is something we do for our job-givers, the employers. They hire us for the sole purpose of enlarging their profit. As job-holders, we are all “minimum wagers” because we get paid only the very minimum our employers can get away with. Once hired, we have no individual personality, no dignity, no humanity left in us during our shift and beyond.

At Walmart, workers are even timed for their bathroom visits, and woe to those with irregular bladders or intestines, for they may exceed their allotted time. No better than a servant in bondage, most job-holders dream of escaping from their jobs and envy the rich and powerful few in society who avoid it altogether. Unsurprisingly, one of the first things the lucky lottery winners or heirs do is to quit their jobs and break from this economic shackle.

For those who respond to “callings” — like priests, free artists and philosophers, teachers, writers, soldiers, revolutionaries, and others like them — the job-work distinction fades considerably. Also, where workers are unionized and control their own work process, as in Germany and Scandinavia, or if labor (and its reward) is widely shared as in Japanese society.

However, America’s workers — unfulfilled and unorganized, and always in financial trouble — can only quit their jobs and commit economic suicide.

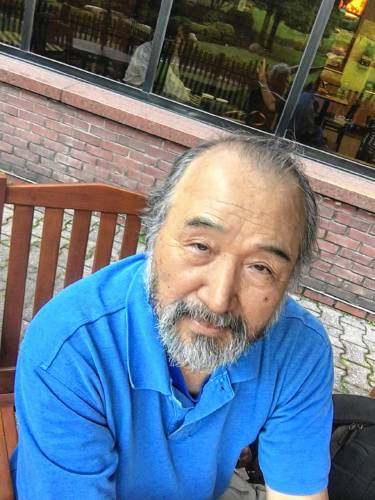

Jon Huer, columnist for the Recorder and retired professor, lives in Greenfield.

My Turn: A ruthless strategy that damages US

My Turn: A ruthless strategy that damages US Analee Wulfkuhle: Shores Ness a vote for Deerfield’s future

Analee Wulfkuhle: Shores Ness a vote for Deerfield’s future Byron Coley: Shores Ness for Select Board

Byron Coley: Shores Ness for Select Board Amy Tibbetts: Northfield residents deserve truth and clarity

Amy Tibbetts: Northfield residents deserve truth and clarity