Cultivating curiosity in the great outdoors: Grower of native plants creates curriculum for school children

| Published: 03-18-2024 3:57 PM |

We celebrate today’s Spring Equinox with Colrain resident Jocelyn Demuth, who designs curricula to encourage Massachusetts children to improve environmental health.

Through her “Five hundred Yard Field Trip” website, Demuth provides teachers with free resources to guide kids in welcoming insects to school grounds. But you needn’t be in school to benefit: anyone can access the information and put into practice strategies to bring about a shift from 20th-century attitudes, which led to widespread spraying, swatting, eradicating, and generally detesting insects. Many of us grew up calling them “bugs,” framing insects as annoyances rather than allies.

Demuth recalls places people took for granted when she was a kid: “We had access to woods and streams, and now we must rebuild those habitats. We’re learning about how flora and fauna operate around us, and how to protect them. This is crucial for the next generation. We ignored important things in years past, and can’t ignore them any longer.” She noted that “when I was growing up, information about plants came mostly from pesticide companies ... We were taught to keep the earth extremely tidy, but it backfired.”

The tidiness message was reinforced by her parents and other adults. “Everyone was supposed to keep our lawns neat, and to use (pesticides and herbicides) on dandelions. Every year, a guy came with a big hose and sprayed all the trees to prevent gypsy moths — whether or not gypsy moths were even an issue in any given year. People sprayed sidewalk cracks to eradicate ants. It’s just what we did in the classic 1970s suburbs.”

In addition to being alienated from natural cycles, said Demuth, “people were distanced from each other. Everyone in the burbs had a house, a lawn, and a driveway. People walking down the street were far enough away so that anyone who might be in their yard could wave, but that space didn’t encourage real conversations.” In less manicured neighborhoods, said Demuth, “people could really talk to each other. In the burbs, though, there was always just enough space so people were essentially removed from one another.”

For this and many other reasons, Demuth believes that modern childhood has become too quiet and sterile, and now she’s offering ways to enhance ecological health during a pivotal time on our planet. “We’ve lost a lot of insects,” she said. “When I was growing up (in the 1970s), Earth didn’t look like this. It was much more common to find bugs stuck to windows, to see moths near streetlights, to spot fireflies. Now, insects are disappearing at a rate of 2.5% per year. If we don’t turn that around, it won’t matter how much progress happens with the climate crisis.” Demuth warns that the collapse of insect populations would spell grim outcomes for humanity.

The good news, however, is that we can turn it around. “Until you have native plants in your yard, you don’t know how sterile the landscape is. There isn’t much to see,” said Demuth. “But once you put in native plants, (insects) soon show up.” With this in mind, Demuth applied for an FDA grant through MDAR (Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources) with the goal of getting kids to grow native plants on school properties so they might witness interconnections between insects and plants, including pollination and the metamorphosis of caterpillars into butterflies.

Although some may know Demuth as a former Latin teacher who’s authored three books on pedagogy, she’s pursuing another career as the proprietor of Checkerspot Farm, where she cultivates and sells native plants, shrubs, and wildflowers to landscapers, schools, and home gardeners. Demuth has been featured in this column before (“Native plants for a living landscape,” Sept. 27, 2022), and her passion for protecting the environment is palpable. “I don’t remember learning anything specifically about insects in school,” she said, “but they were all around me anyway. My friends and I came into contact with insects just by having time in nature, by exploring.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

New buyer of Bernardston’s Windmill Motel looks to resell it, attorney says

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

Ethics Commission raps former Leyden police chief, captain for conflict of interest violations

Ethics Commission raps former Leyden police chief, captain for conflict of interest violations

Demuth wonders: “How can the next generation be better stewards for survival if we don’t teach them?” and she points out that contemporary kids “can’t teach themselves, if the life forms simply aren’t out there.” The MDAR grant stipulates that Demuth will create four units over a period of two years. The first unit, “The Pussytoes Project,” is already downloaded to the website. Another unit for students in grades 3-5, “Caterpillarpalooza,” will be ready this spring. Two more, for middle school students, will be uploaded next year.

“Most science curricula concentrate on systems, which little kids aren’t big on,” said Demuth. She created the K-2 unit so that kids could focus on one plant. Her website explains that pussytoes (antennaria) are a wonderful, low-growing plant that sends up distinctive white flowers in May. The plant is one of the hosts of the American Lady butterfly, “the life cycle of which can be observed on the plant.” Demuth designed the unit so students can learn about the caterpillar’s diet, adaptations, and metamorphosis, as well as the mechanics of pollination. She designed the unit to satisfy many of the K-2 life science standards for Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire and New York.

“The unit for grades 3-5, Caterpillarpalooza, involves a bunch of different plants, so students can compare and contrast,” said Demuth. “We bring in flowers and native grasses that support a variety of caterpillars and other pollinators, and all of the plants selected are drought-proof and non-aggressive.” Demuth intentionally makes the units playful to encourage curiosity about the outdoors “beyond the soccer field or parking lot.” She also aims to make the material “fit smoothly into teachers’ curricula with little or no need for revision or independent research.”

“The Five hundred Yard Field Trip” website also contains information relating to the main reasons for insect decline, including the loss of habitat crucial to the survival of native plants. “Insects and native plants have evolved together on the continent for millions of years,” Demuth said, explaining that many of the ornamental flowers and bushes commonly found on school grounds or around neighborhoods originate from other continents. Leaves and seeds of those plants don’t attract local insects, so those plants are considered sterile.

Demuth’s website provides clear listings — including a map — of where to access the plants she recommends. “I contacted all the native plant nurseries I could find in the state, because they have to be on board with this, too. Teachers get a list of plants they’re supposed to buy, and I want them to be able to go to a nursery and ask for what they need.” Proprietors of native plant nurseries were excited to hear from Demuth. “Nobody’s been in this business very long,” she said. “It’s a relatively new sector. [Native plant growers] are working seven days a week, and are often exhausted. Everyone I spoke to was very enthusiastic.”

When Demuth was a kid, the natural science field trips she and her classmates went on involved getting on a bus. “To go to woods or wetlands from school — to see nature — we had to travel. So my idea is, let’s not leave school property in order to study ecology. Let’s take some steps so kids can just go outside and look.”

To visit Demuth’s new website: www.fivehundredyardfieldtrip.com.

Eveline MacDougall is the author of “Fiery Hope,” and mostly homeschooled her kid, mostly outdoors. To contact: eveline@amandlachorus.org.

Proof that it’s never too late: Solo exhibit and free workshops honor the late Frederick Gao, a Belchertown resident who became a painter in his last five years

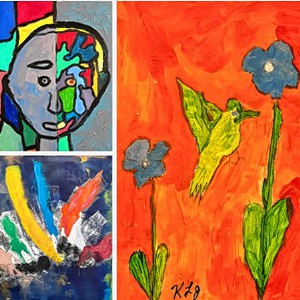

Proof that it’s never too late: Solo exhibit and free workshops honor the late Frederick Gao, a Belchertown resident who became a painter in his last five years Self-expression on display: ServiceNet members’ artworks on view at Greenfield Public Library through end of May

Self-expression on display: ServiceNet members’ artworks on view at Greenfield Public Library through end of May Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how

Embracing both new and old: Da Camera Singers celebrates 50 years in the best way they know how Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week

Time to celebrate kids and books: Mass Kids Lit Fest offers a wealth of programs in Valley during Children’s Book Week