My Turn: How to welcome a refugee family into your community

| Published: 04-15-2024 4:45 PM |

The loud and shameless politics that surrounds the issue of undocumented immigration makes it easy to miss the moves that the Biden administration has been making in the realm of legal immigration, from rebuilding the refugee program to expediting the processing of green card and citizenship applications.

One initiative that I don’t believe gets enough attention is the relatively recent creation of the Welcome.US program, which has allowed private citizens to sponsor incoming refugees.

You might be under the impression that in the land of entrepreneurship and civic action private sponsorship has always been possible, but you’d be wrong: Until two years ago, only a handful of organizations contracted by the State Department could organize and manage “communities of care” for individuals and families seeking safety in the United States.

Welcome.US, along with its offspring, the Welcome Corps, now makes it possible for churches and synagogues, veterans associations, immigrant organizations, or even just groups of neighbors, co-workers and friends to bring refugees into their towns and help them adjust to their new life.

Massachusetts is, by and large, a rich, liberal state and the percentage of its foreign-born population (18%) is higher than that of Texas (17.2%), Arizona (13.1%) and the U.S. as a whole (13.9%). So you’d expect Welcome.US to have plenty of traction in these parts. True, Boston and its suburbs are currently dealing with the challenge of caring for thousands of asylum-seekers recently arrived from the southern border, but that still leaves huge swaths of the state — and in particular western Massachusetts — well positioned to resettle refugees.

The news of the program, however, does not seem to have reached many of the proud communities where every other house has a sign that says, “Immigrants are welcome here!”

There are models to be followed, though — towns that have indeed rallied to the aid of a refugee family (or several of them) and are doing the hard work of moving them toward self-sufficiency. The Berkshire County community of Williamstown, for example, has come together to care for a Haitian family of four — Josnel and Yousmane St. Fleur and their two small children — who arrived in the United States last summer through the Welcome.US program.

A resident of Williamstown, automotive journalist and off-road racer Sue Mead first met Josnel in 2003 in a village outside of the Haitian port city of Cap-Haïtien and was impressed by the boy’s resilience in the difficult circumstances in which he lived. Over the years, they kept in touch and she supported him as best she could.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

Authorities ID victim in Greenfield slaying

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

State records show Northfield EMS chief’s paramedic license suspended over failure to transport infant

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

Police report details grisly crime scene in Greenfield

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

On The Ridge with Joe Judd: What time should you turkey hunt?

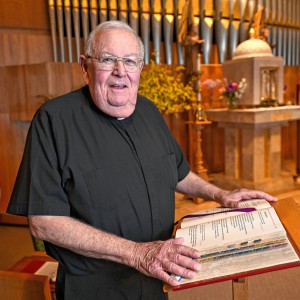

‘I have found great happiness’: The Rev. Timothy Campoli marks 50 years as Catholic priest

‘I have found great happiness’: The Rev. Timothy Campoli marks 50 years as Catholic priest

Formed 25,000 years ago, Millers River a historic ‘jewel’

Formed 25,000 years ago, Millers River a historic ‘jewel’

But conflict and depredation have lately been making life in Haiti extremely dangerous, and Josnel, now a husband and a father in his early 30s, needed to get out. The newly unveiled Welcome.US program could bring the family to the U.S. on a temporary humanitarian visa, but the day-to-day support would have to be found locally.

Mead turned to Williamstown’s First Congregational Church, where Bridget Spann, the outreach community organizer, knew what needed to be put in place to welcome refugees.

Once a family has been approved for resettlement by the American immigration authorities, the absolute priority is finding short-term housing and lining up some necessities, such as food, clothes and furniture. Then comes taking care of immediate medical needs, enrolling children in school, applying to state and federal social programs, and eventually finding decent jobs for the adults.

This is where the wider community comes in. A Realtor who had worked with Spann before offered one of her properties for the family to live in, despite the adults being unemployed as of yet. The First Congregational Church paid the rent for the first three months. Mead’s dentist in North Adams was willing to work with the family even though she didn’t usually accept Medicare. Ethan Zuckerman, one of the family’s fiscal sponsors, introduced Josnel to the small West African and Caribbean communities in the Pittsfield area. All in all, some 15 core people, along with several dozen others on the periphery, pitched in to help the St. Fleurs adapt to their new surroundings.

“One of the host team members tapped a member of her congregation who speaks French. And that person said, ‘I’m not available because of family stuff, but I can throw this out to a group of French speakers that I meet with every week,” Spann recounts. “And through that, we’ve essentially had French interpreters for every meeting we’ve had with the family. It’s been a gift to know these French speakers in our community who want to be of assistance and can help with this one piece. Part of how this effort gets off the ground is identifying who can be an ongoing host team member and who can fulfill one little piece of the puzzle.”

Welcoming refugees into your community, Zuckerman agrees, is a win-win proposition.

“People who come in on a variety of temporary protected statuses are good actors in society,” he says. “They’re working, they’re contributing, they’re paying taxes. We’re at extremely low unemployment. We’re at real need for work. One thing that I always point out to my neighbors is that the Berkshires are shrinking. We are still losing population in each decennial census. And if we can become a home for migrants and for refugees, that's part of how we're going to keep supporting our infrastructures.

“I've lived just outside of Pittsfield for almost 30 years, and I've watched us shut down churches, schools, health care facilities. Migration is one of the ways we deal with that. Migration is one of the ways that we adapt to that future.”

Razvan Sibii is a senior lecturer of journalism at UMass Amherst. He writes a monthly column on immigration. He can be contacted at razvan@umass.edu.

Columnist Daniel Cantor Yalowitz: Staying real, remaining humble

Columnist Daniel Cantor Yalowitz: Staying real, remaining humble Araceli Katalin McCoy: Why we should change the voting age to 16

Araceli Katalin McCoy: Why we should change the voting age to 16 Emily Gaylord: Shores Ness brings experience

Emily Gaylord: Shores Ness brings experience Arlene and Doug Tierney: Vote for Blake Gilmore on May 6

Arlene and Doug Tierney: Vote for Blake Gilmore on May 6